A year after its inception, the magazine has created a bond with our readers and that is the gratitude we owe them and the happiness they owe us. Between the two, there is the responsibility of doing more and better, and our loyalty to that job. As Samuel Beckett says in Worstward Ho – he who was, and certainly will be again, in these pages – even when we fail we have to try again and learn to fail better.

Our readers’ voices have often reached us – and in those voices there has been the sound of someone saying something larger than inadequate opinions or insipid comments. Those voices have spoken reason, additions, suggestions, convictions, proposals, enthusiasm, loyalty, and omens.

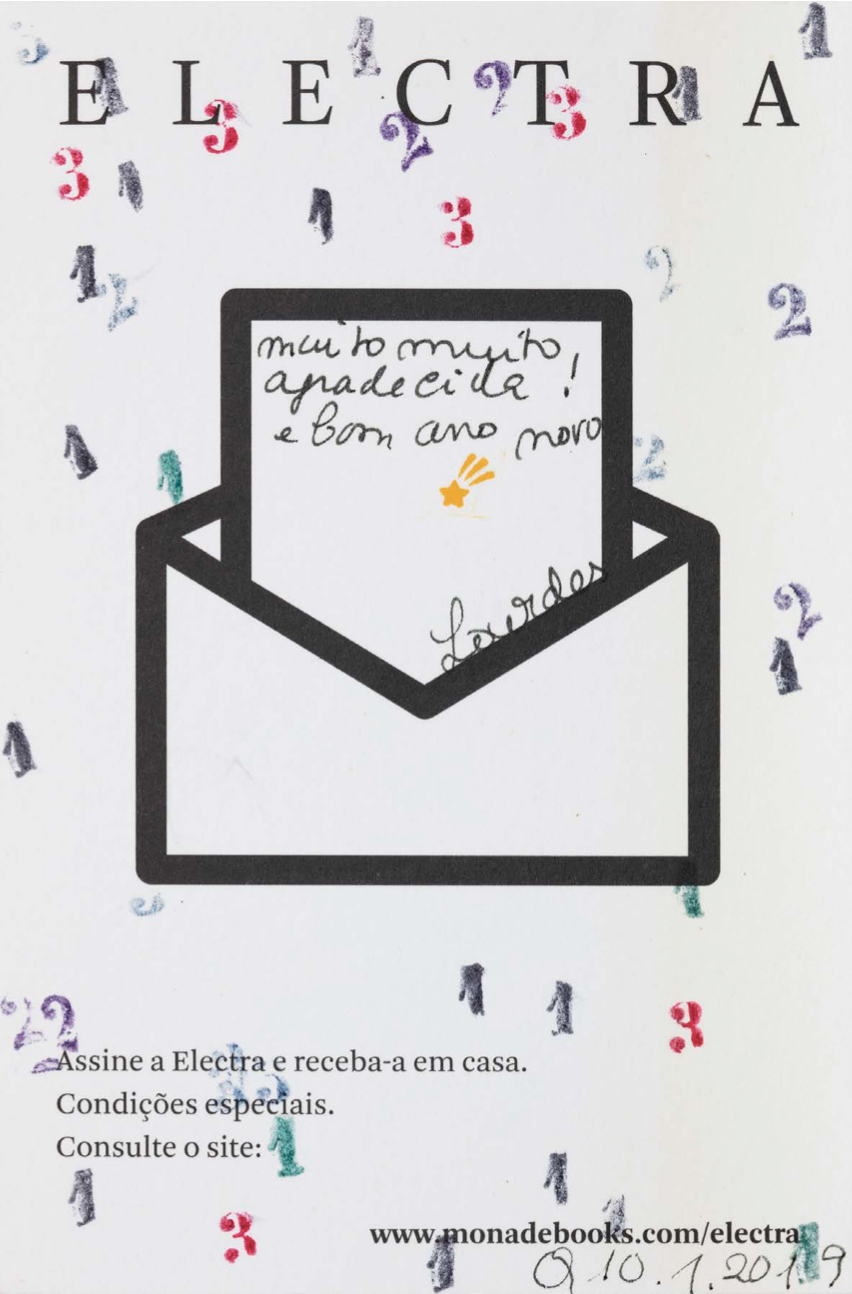

Among them we choose, as an example and symbol, the subscription postcard which Lourdes Castro – the artist whose portfolio distinguished our first issue – transformed and sent back to us: we had sent it to her inside the magazine. Like all great artists, by making it her own, Lourdes made it even more ours. Adding wishes and numbers to it, her fairy hand practised a propitiatory magic that I hope will inspire us too.

During this year, the words and images that have made the magazine have brought us subjects, people, artistic works, ideas, projects, opinions, and debates. A year is not enough for any assessment other than that that drives us on.

As we have already said, we have been and are contemporaries of a time, our own, which is also made up of times past and times to come, times left behind and failed times, lived times and imagined times, accepted times and rejected times. Of that we are aware. When we look at this time, we do not allow ourselves to be blinded by its assiduously artificial brightness or by its frequently simulated darkness.

Here, looking at time should mean looking at what passes and what remains of it, contemplating its configurations and confrontations, questioning its deceptions and enigmas, and observing its paralyses and escapes.

In this issue, where time becomes memory, renovation and impulse, we dedicate a part of it to ‘youth’. Upon reflection, we can perhaps conclude that we turn youth into a kind of back-ghost (the same way we talk about backlighting). And still we show it as one of the most cruel and hypocritical paradoxes.

At the same time as we raise youth to the gods on high, we throw to the demons in hell those young women and men on whose faces youth casts a light without shadows, save ours when we touch it.

These are the people in whose name our culture practised one of its founding crimes by condemning Socrates to death, after accusing him of not respecting the city’s gods and corrupting youth with his words. That showed how ignorance is a danger to wisdom and foolishness a threat to virtue.

Paul Auster once said in an interview that in his generation and in previous ones the youth wanted to change the world. He then added that today’s youth just wants to find a place there. In the end, it neither changes the world nor finds its place. I could say with Rimbaud: ‘Oisive jeunesse / À tout asservie / Par délicatesse / J’ai perdu ma vie’ [Idle youth/ Enslaved to everything/ By being too sensitive / I have wasted my life].

In the diary that he wrote for this issue, the very young and already recognised opera and theatre stage director, playwright and costume designer Rafael R. Villalobos, who in a premonition of things to come once staged Richard Strauss’ Electra, talks about his life and what it contains of rules and exceptions. Running through his days there is a breath of life, vigour and even vertigo, which, like the time of St. Augustine, comes from the future.

Based in his room-observatory, full of dust from the fumigations with which he tried to breathe the unbreathable, Marcel Proust knew more about life than those who turn it into a victory. So in this issue we talk about Proust and what is seldom mentioned when we talk about him.

Speaking of Proust, a lot is said about time, love, jealousy, art, memory, illness, death, cruelty, mundanity, snobbery, and happiness. We talk about money and what it was, represented and served for in Proust’s world. His financial life knew a lot of ups and some downs. It is said that one day, after dinner at the Hotel Ritz in Paris, where he had his habits and haunts, friends and loves, he realised that he did not have enough money to give the waiter the magnificent tip he usually graced him with, in a subtle show of elegance. Then he suddenly had this brilliant idea: he asked the doorman, who always gave him a smiling and astute bow, for that same amount, so he could leave the usual and expected tip. And this set the world right.

Making a magazine like Electra is repeating Proust and Lourdes Castro’s generous gesture. It is asking the reader to lend us the very thing with which we give them what they expect. That currency’s name is high standards. We will continue to give it because we will continue to receive it. That is our goal, our contract, our truth.

*Translated by Ana Macedo

Share article