In the feminist and civil rights movement, from women’s suffrage to the 1970s, black women were at a crossroads: they could not speak about gender issues in the black movement because this would divert attention from the important struggle against racial oppression; on the other hand, to bring racial questions to the feminist movement would divert attention from the denunciation of male chauvinism. In spite of the acclaimed alliances and the longed-for ‘sisterhood’, the families that gradually composed feminist movements would look but not see each other, or not want to see the differences and urgent issues. However, visibility and leadership leant towards white middle-class feminists who dissociated race from gender. The American author bell hooks felt she had no place within a female liberation movement that did not include two crucial elements of her life – ‘having been born black and having been born female’ (p. 28). She wrote, in question-mode, in search of that intersectional identity, moving from her own personal experience to a social experience: ‘Before I could demand that others listen to me, I had to listen to myself…’ (p. 9). The racism and sexism black women had been subjected to since slavery contributed to their deplorable conditions and status: ‘No other group in America has so had their identity socialized out of existence as have black women. We are rarely recognized as a group separate and distinct from black men, or as a present part of the larger group “women” in this culture. When black people are talked about, sexism militates against the acknowledgement of the interests of black women; when women are talked about, racism militates against a recognition of black female interests’ (p. 21).

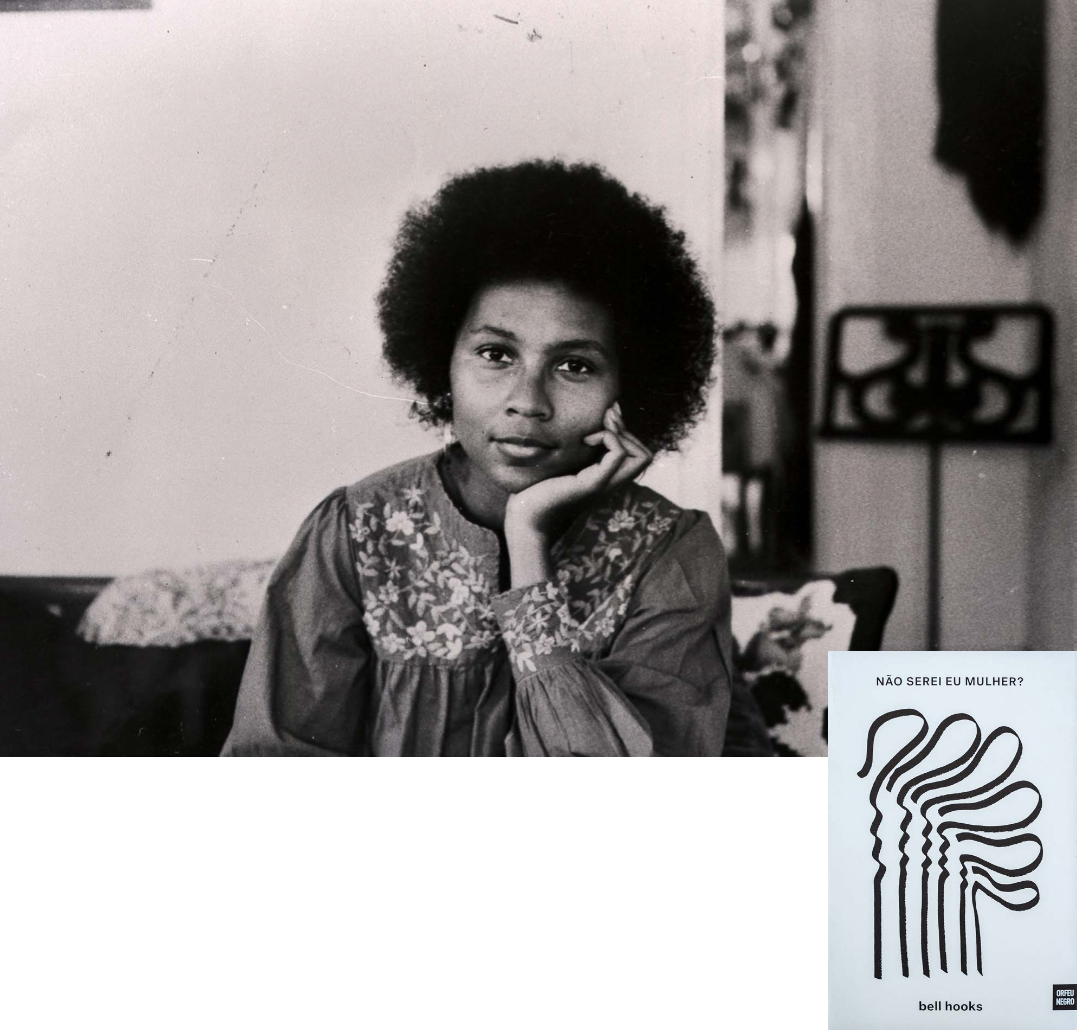

Written in 1981 by a ‘bold young black female from rural Kentucky’ (p. 9), while she was studying at university and starting to engage in politics, with the ambition to become a free, independent woman – although only published when she was nearly thirty – Ain’t I a Woman? became a classic on the difficult dispute of black women with feminism, and on the theory that relates race and gender. In a very colloquial and sometimes circular style in terms of its argumentation, the book journeys through history, literature (essays and journalism) and the challenges of American society, to revisit the impact of sexism during slavery, the devaluation of black womanhood, the sexism of blacks and whites, the links between imperialism and sexism, the disguised racism in feminism and the participation of black women in feminism. To conclude, institutionalised racism and sexism – patriarchy – form the base of the American social structure, but we could say the same about so many others, and it is still within this pattern that people are socialised.

The author criticises the various feminisms that have left out the social experiences and places of black women, who necessarily paved their own way to resistance. The identity woman, which Judith Butler would deconstruct by questioning the construction of gender, is contested by hooks in view of the systematic exclusion of a vast group of women, who have been racially and sexually oppressed throughout history, ‘always perceived as Others, as de-humanized beings’ (p. 188). The author reminds the reader how the American feminist movement was initially incapable of thinking of whiteness as a privileged category: it ignored and stereotyped black women, sometimes taking advantage of the subalternity they were relegated to. ‘It was not in the opportunistic interests of white middle and upper class participants in the women’s movement to draw attention to the plight of poor women, or to the specific plight of black women’ (p. 193) and so sexism, racism and classism were reinforced. Moreover, hooks points to the class constraints in feminist movements, where white women were always at an advantage: more informed and with access to education and greater ability to lead. She also mentions that the feminist movement was hardly able to denounce capitalism, making an idea of liberation (according to the white capitalist patriarch) correspond to the acquisition of economic status and financial power. ‘This emphasis on work was yet another indication of the extent to which the white female liberationists’ perception of reality was totally narcissistic, classist, and racist’ (p. 197), where work often meant – especially for black women – the opposite of liberation.

Lamenting the difficulties black women encountered in organising themselves and the moments in which, due to hierarchical struggles or internalised prejudice, they gradually repressed their desires for liberation, hooks recalls some of the progressive voices from the 19th century. Ain’t I a Woman? was how the speech of Sojourner Truth (1797-1883), delivered at the 1852 Women’s Convention in Ohio, became known. Before an assembly of white women and men, she repeated the abolitionist slogan, evoking the lost humanity of enslaved people (according to hooks, she even showed her breasts to prove she was a woman). Although she was born a slave in the state of New York, Truth won her freedom and was one of the first black women with an anti-slavery public discourse that also advocated women’s rights. But hooks turns to many other voices to show that resistance on the part of black women has always existed.

We delve into the traumatic experiences of the black female slave, on board the slave-trading ships, later ‘exploited as a laborer in the fields, a worker in the domestic household, a breeder, and as an object of white male sexual assault’ (p. 39). And we could add ‘of black male sexual assault’, since the system legitimated the sexual exploitation of black women. The author adds that the rape of female slaves was an institutionalised method of terrorism with the purpose of demoralising and dehumanising black women, with impacts still felt today. While the world was generally misogynous, the diversion from Christian doctrine in the 19th century changed the way women were perceived: the transition from ‘the image of white woman as sinful and sexual to that of white woman as virtuous lady’ (p. 53) occurred at the same time as the sexual exploitation of enslaved black women, reinforced by myths about their lack of morals and promiscuity. Black womanhood was always devalued, namely through the false idea of the matriarch, the strong woman who can handle anything – one of the stereotypes still affecting black women, who are discriminated against at work and in society, and – not seldom – still morally condemned.

In addition, bell hooks mentions that anti-racist movements and black nationalisms have also proved to be misogynous and not very interested in moving out of the patriarchal cloister. Although they called for the end of racial divisions, they reinforced sexist divides. In other words, within their communities, black women always lived under a dominant male chauvinism.

This book, now translated into Portuguese by Orfeu Negro (although there is a free translation from Plataforma Guetto), is an important acquisition for gender studies, black studies and philosophy. It is essential reading in a context where the fight against ethnic/racial and gender discrimination still has a long way to go. The association FEMAFRO, led by black African/African-descendant women, including young women, as well as the recent INMUNE, an ‘intersectional and anti-racist feminist’ entity, are active in opposing the historical and present silencing of black women in Portuguese society.

There has been talk about the importance of putting an end to this skewed denial of racism. Here, bell hooks shows how the struggles against patriarchy and racism have to follow, for they are the political foundation that brings breadth and sincerity to the feminist movement – not making it an instrument of the interests of certain women, but one of all women. Liberation would gain in significance by representing the experiences of different women, with the vulnerability and strength that that entails, building a sisterhood free of competition and negligence.

*Translated by Moira Difelice

Share article