The focus of this fifth issue of Electra is young people and youth. Even though the articles included here branch out in different directions, our starting point is the observation that youth as a separate social category is now coming to an end. It has thus been a short-lived invention that is drawing to a strange close – due to the excessive expansion of its domain and the usurpation of its status. Youth is no longer a transitional phase between childhood and adulthood but rather an almost permanent state. It has lost most of the characteristics that tied it to the biological and mental stages of human development to become a predominantly cultural phenomenon. The world is full of ‘young adults’. Youth is two different things at once: an ideal that manifests itself in a world of representations, phantasmagorias and aesthetic and social codes that have become universal and reach across age barriers; and an extended and non-temporary state in an era when gaining independence (by entering the world of work and starting a family) is occurring later and later in the western world.

Youth’s most common condition is associated with a word that is now commonplace: precariousness. The great Russian linguist Roman Jakobson wrote an essay in the 1930s, following Mayakovsky’s suicide and the purge and deportation of Soviet poets, writers and artists, entitled ‘The Generation that Squandered its Poets’. Our generation has squandered its youth, keeping them shut out. This is a disaster – and a cultural one too – which advances silently, a cause of social imbalance and the implosion of institutions (primarily schools and universities). Precariousness as an inescapable condition, on the one hand, and the deep hiatus between an established generation and one which arrived at a time when the idea of the future – the driver of all political and social action – had already lost its meaning, on the other, are the answer to a question that is often asked: why has no collective identity – something similar to a social movement – emerged around youth’s grievances? In other words, why is youth not replaced by a historical subject when the conditions for this appear to have been created?

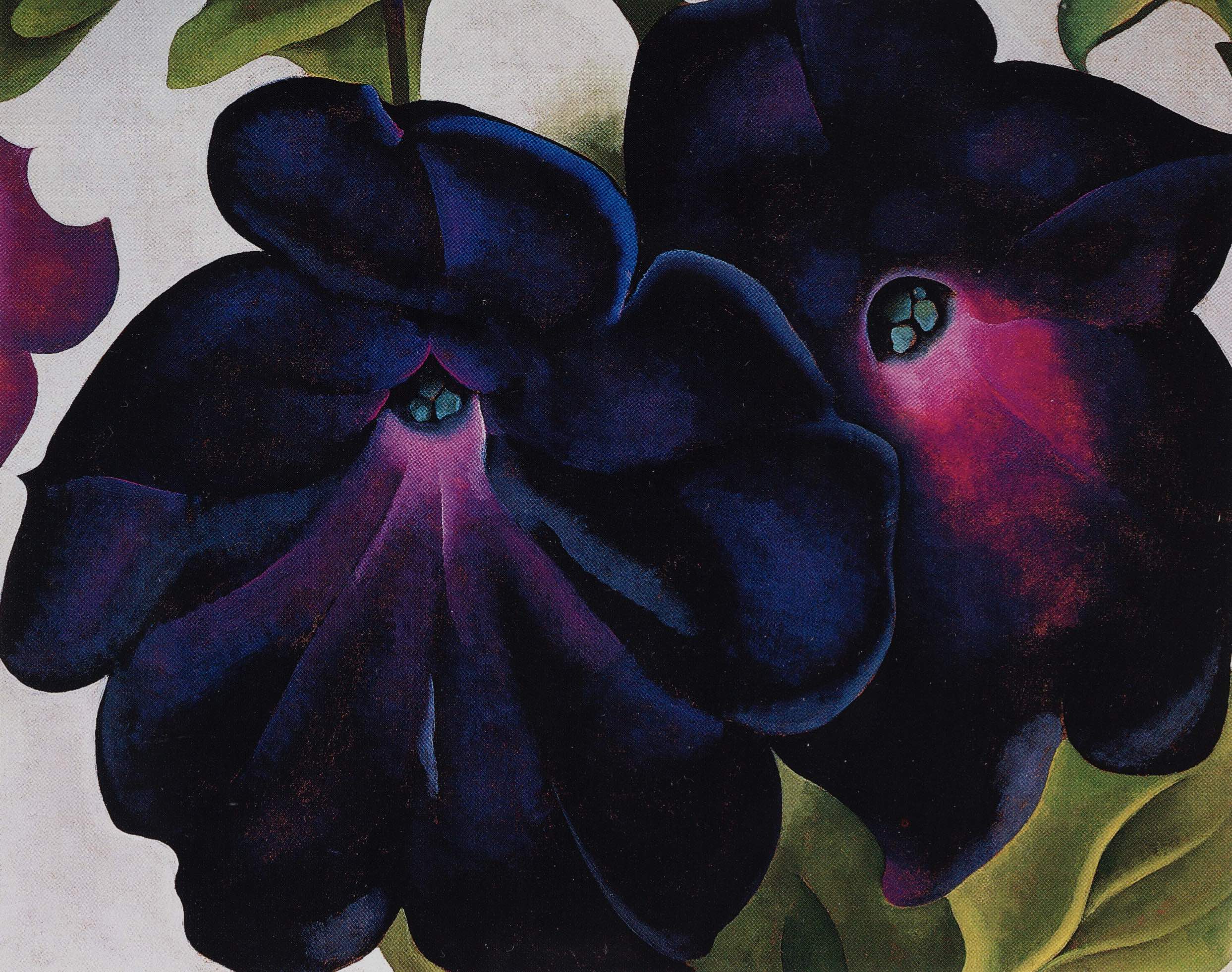

With youth’s huge political significance extinguished and the ‘spiritual’ – intellectual – force that gave it messianic power at various times in the 20th century (May 1968, for example) expunged, its strength has been confined to profane illuminations of ‘image’. Today, it is noticeable that our imagination has been monopolised by images of young bodies, which almost exclusively occupy the public realm in film, TV, advertising and fashion. It is hard to imagine beauty, health, vitality, sexuality – and all their variations – without reference to the young body. This, then, is the body as it ‘should be’, the body as biopolitically correct. Which brings us to another way of characterising youth, as something no longer defined by an ideal, by a notion of the world (as with post-war youth up until May 1968), but by image. An ideal is something one aspires to and constitutes a policy; it determines action and creates a style. Image, however, leads to passive mimesis, a state at one with the phenomenon of the aestheticisation of society and the forms of meaning that correspond to it.

Share article