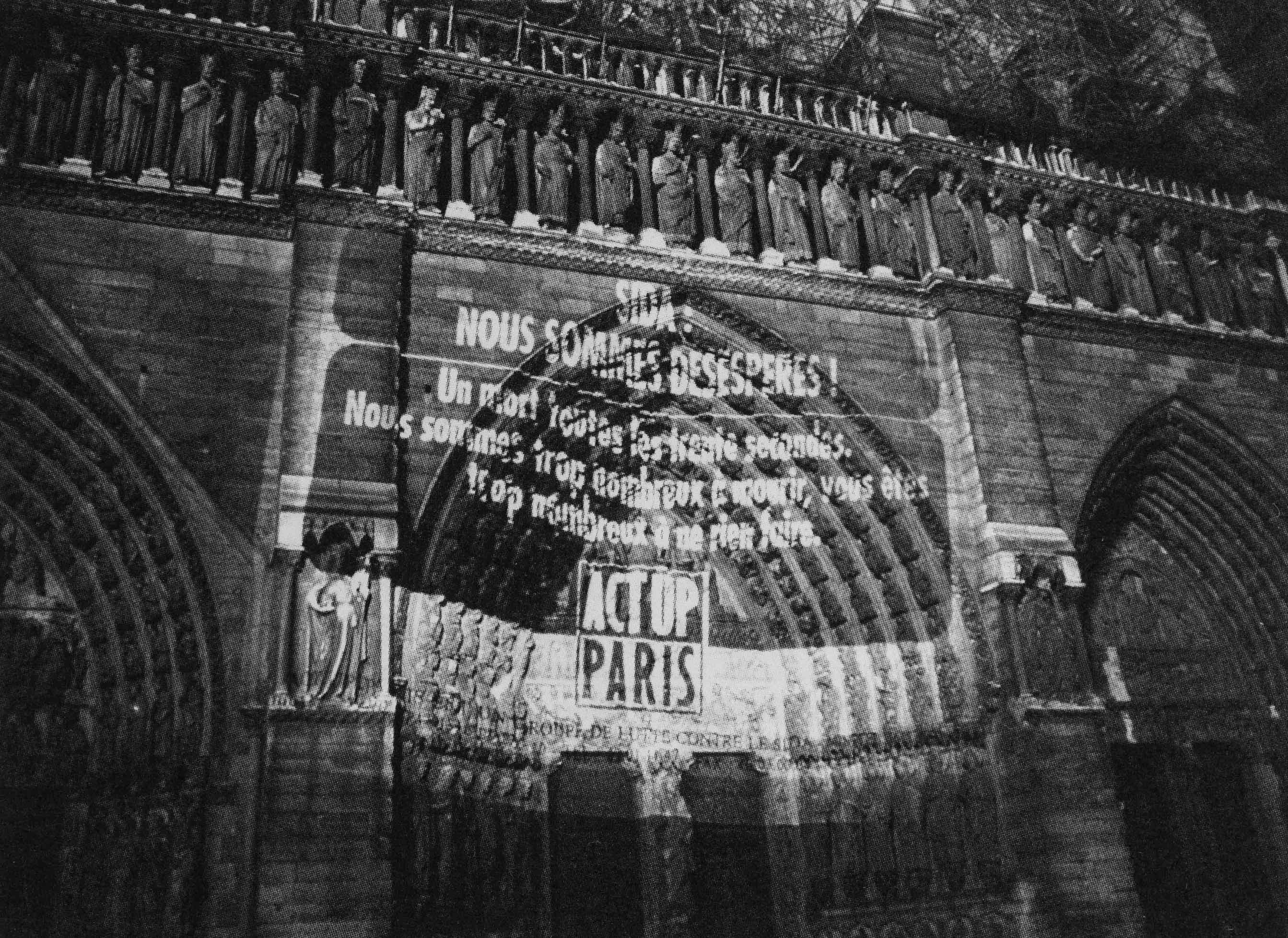

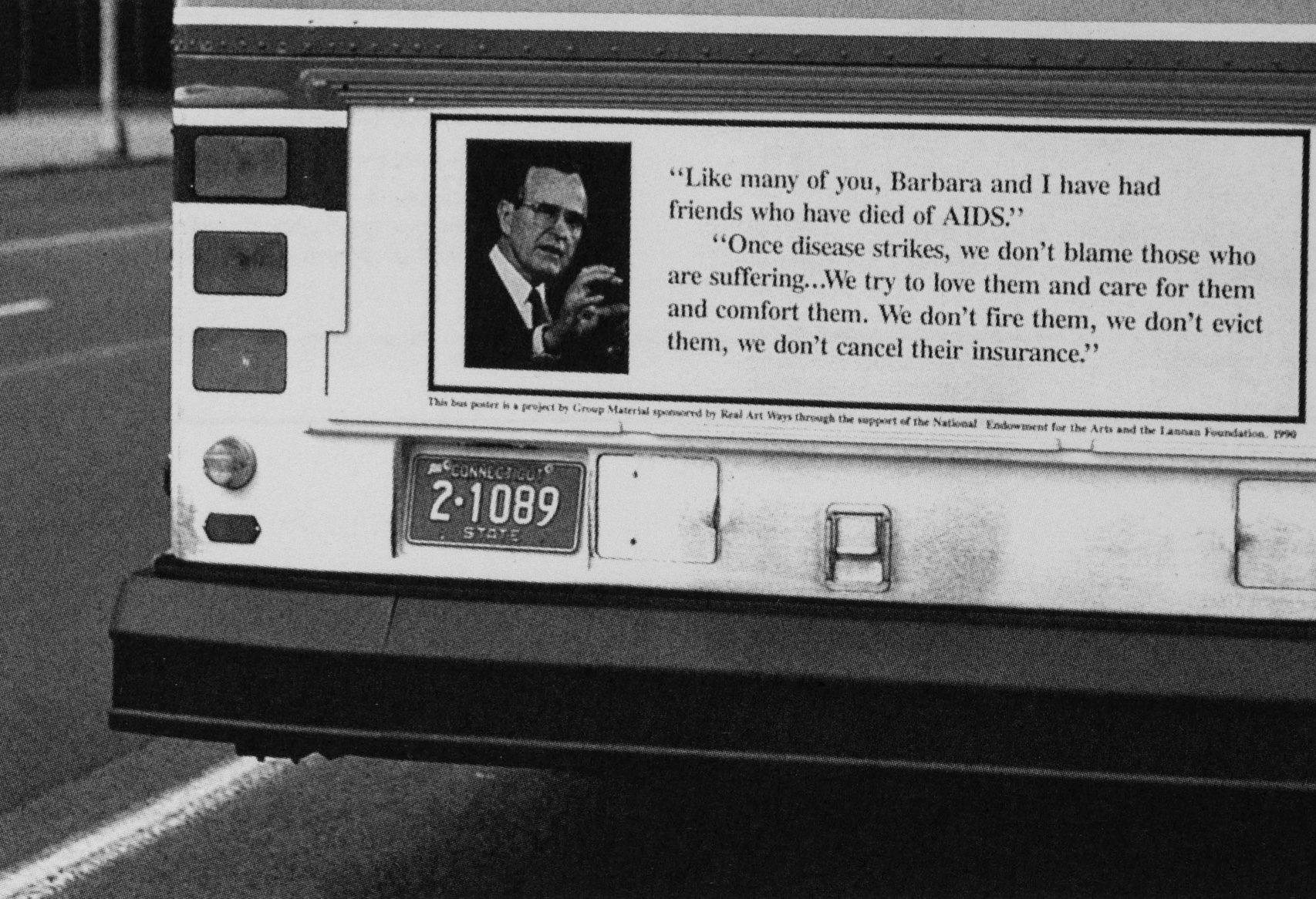

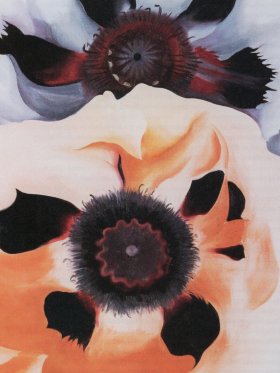

Elisabeth Lebovici (b. 1953) is a historian, art critic and author of monographs about contemporary artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Chantal Akerman and Zoe Leonard. She studied philosophy and art history at the University of Paris X and in 1979 joined the curatorial Independent Study Program at the Whitney Museum in New York. She was editor of Beaux-Arts Magazine from 1987 to 1989. Her work as a critic continued on the cultural pages of Libération newspaper between 1991 and 2008. Elisabeth Lebovici immersed herself in the arts world, where the AIDS epidemic caused havoc, instilled an atmosphere of morbid terror and ended the mood of liberation demanded and conquered in the 1960s. She heeded the call of activism and joined the Act Up movement in Paris. The movement engaged in a political struggle against the way in which institutions were handling the disease by closing their eyes to it as far as possible or equating it to sacrificial representations, ghoulish images and the passional suffering of the ‘victims’, thereby encouraging a view of the disease as a punishment. Act Up, which was founded in New York, brought AIDS into the political struggle and used political weapons.

In 2017, Lebovici bore witness to these times in a book entitled Ce que le sida m’a fait. Art et activisme à la fin du XXième siècle [What AIDS did to me. Art and activism in the late 20th century]. Although the title is in the first person, it is by no means a personal memoire; nevertheless it could only have been written by someone with intense experience of the milieu where the activism was at its fiercest. The book includes interviews, monographs about artists, essays and an introduction that explains why this diversity can form a unit. The pages contain contributions by many important artists and authors from the 1980s and 1990s: Nan Goldin, Félix González-Torres, General Idea, Gregg Bordowitz, Zoe Leonard, Lionel Soukaz, Roni Horn, Philippe Thomas and many others. The author warns us right at the start that it is not ‘a list of the dead or a catalogue of HIV appearances’.

A 1987 number of October, an important American art criticism and theory magazine, said, ‘AIDS is an epidemic with no representation.’ It was this lack of representation that was so much to blame for the spread of the disease and so harsh for those infected by it that it spawned an activism in the artistic world, which was hard hit by the epidemic. Nan Goldin was a pioneer in 1989. She set up an exhibition at the Artists Space in New York entitled Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing. It was against disappearance, against invisibility and became a cause that mobilised many artists, in different ways, some which were not actually reflected by explicit mobilisation. Art spaces often opened to what was happening in the city, streets, homes and hospitals, as the epidemic needed public art. Speaking about her book, Lebovici quotes this statement by Jacques Rancière. ‘Artists want to change the points of reference of what is visible and enunciable, showing what was not seen, showing what was not very clearly seen in a different way.’ His was a general statement. It belonged to a different context and was not motivated by visibility issues raised by moralistic, erroneous or inadequate responses to the epidemic from institutions and public authorities. However, Stuart Hall, a well-known cultural studies theorist drew attention to an urgent task to deal with the ‘AIDS crisis’. ‘Analyse what comes from the political idea and complexities of representation, the effects of language, textuality as a place of life and death.’ Lebovici’s book answered all these proposals and challenges while also bearing witness to those ‘AIDS years’ that were experienced in constant panic and mourning, where the utopias and euphoria of the previous two decades sank without a trace. By using the pronoun ‘me’ in her book title, she subscribed to this statement by González-Torres, a Cuban-born artist who died of AIDS in the United States in 1996 at the age of 39: ‘In this time of Aids, we all live and die in Aids, whether or not we die of Aids.’

Share article