A charismatic and experienced cinema sound designer was once asked what makes the acoustic environment of Lisbon unique. Disconcertingly, his reply was, ‘Nothing!’ Lisbon’s soundscape is indistinguishable from that of any other city because all cities sound more and more alike under the pervasive, continuous, monotonous hum of traffic. Vasco Pimentel – the experienced sound designer in question – eventually admitted there were areas within the city that had characteristic sounds, and that his hyperbolical, iconoclastic quip had been merely rhetorical. Still, it is surprising (and ironic) to find that some of the more distinctive sounds of Lisbon come, even now, from the Ponte 25 de Abril suspension bridge built in 1966. The whirring of the relentless flow of traffic over the steel grid roadway produces a peculiar and mesmerising drone that inspired Bill Fontana (the American artist and sound arts pioneer) to create an in-situ, live audio/video installation – Shadow Soundings – for the oval gallery of the city’s Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology in 2017-2018. Fontana had been developing acoustic bridge-related projects since the 1980s, such as the piece on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, with which this bridge in Lisbon is often compared. However, as Fontana admitted, the Golden Gate structure lacks that specific whirr that carries naturally as far as Alcântara, on the north bank of the river Tagus, and can be heard in several streets in the city depending on atmospheric and acoustic conditions. In the words of the Canadian composer and theoriser of soundscapes Murray Schafer, this sound acts as a keynote sound: like the tonal centre or tonic of a musical score, it sets the tonality of a place, even when almost undetectable or unnoticed amid our daily affairs.1 Conversely, a wider interpretation of Schafer’s theory could also consider it a soundmark: a sound that is particularly significant to the identity of a certain community such as, for instance, the sequence played by the chimes of Big Ben in Westminster, London. However, this is not how the bridge sound works for Lisboners. It often goes unnoticed, heard as merely an acoustic effect of the metal structure and the city’s geomorphology, although inhabitants may remember the sounding of horns that was famously added to it some twenty-five years ago – an acoustic symbol of defiance, of civil disobedience even, against an unpopular policy. Together, this means that a soundscape should be considered not only in its acoustic and ecological dimensions – as the set of sounds of a given physical and social environment – but also in its historical, anthropological and cultural aspects, which involve modes of perception, representation and purpose. These aspects reveal the complex web of social and symbolic exchanges, as well as the aesthetics of a particular community at a given historical time. When we actively listen to a city, when we are aware of its soundscape, we can access those aspects of space and urban life that, though often invisible, are perceptible or at least complementary to what we can apprehend using information from other perceptual modalities (hearing, touch, kinaesthesia and proprioception), which can unveil the many qualities of the urban experience. The landscape reveals the countless events, movements, encounters, clashes, gestures, challenges, voices and intonations that are continuously being produced in different urban spaces. In fact, every sound we hear not only refers to its source, but also to the way in which the sound events occur and the effects of their propagation, reflection, resonance or absorption in a given environment. The qualities of each sound – its attack, its partials and transients, its mass, its grain, fluidity, brightness and clarity – are audible signs of the interactions, rhythms, places and even emotions that affect us in our daily experiences of the city.

A charismatic and experienced cinema sound designer was once asked what makes the acoustic environment of Lisbon unique. Disconcertingly, his reply was, ‘Nothing!’ Lisbon’s soundscape is indistinguishable from that of any other city because all cities sound more and more alike under the pervasive, continuous, monotonous hum of traffic. Vasco Pimentel – the experienced sound designer in question – eventually admitted there were areas within the city that had characteristic sounds, and that his hyperbolical, iconoclastic quip had been merely rhetorical. Still, it is surprising (and ironic) to find that some of the more distinctive sounds of Lisbon come, even now, from the Ponte 25 de Abril suspension bridge built in 1966.

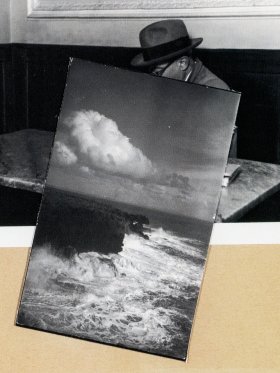

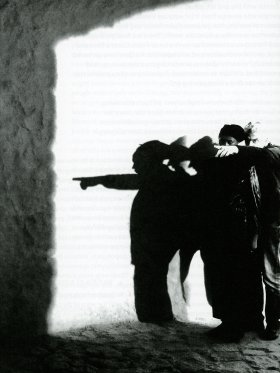

"The whirring of the relentless flow of traffic over the bridge’s steel grid roadway produces a peculiar and mesmerising drone that inspired Bill Fontana (the American artist and sound arts pioneer) to create an in-situ, live audio/video installation – Shadow Soundings."

If we stroll around the city today ‘con le orecchie più attente che gli occhi’ [with an attentive eye and an even more attentive ear] – obeying Luigi Russolo’s command in his famous manifesto L’Arte dei rumori (1913) – we can hear the sounds that emerge from the background noise of road traffic and that stand out as the signals of different sound events. In a city of Catholic traditions such as Lisbon, despite the modern tendency to laicisation and the noise of industrial civilisation, we can still hear the bells sounding from the many churches clustered in the historical centre or scattered throughout the city – a city that a century and a half ago was still a series of country estates and farmlands owned by religious orders. The church bells often go unnoticed, not only because they are masked by the increasing noise of road and air traffic and of cement mixers working to reconfigure the city, but also because they have become inaudible to contemporary ears that are no longer accustomed to the rings, chimes, peals and death knells from the belfries that used to order everyday life.

1. See Murray Schafer, The Tuning of the World, New York: Knopf, 1977.

[...]

Share article