From the point of view of the history of ideas, the philosophical seasons of curiosity lie in Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Montaigne and Hobbes. Curiosity was a central idea in the Enlightenment. Neil Kenny, an expert on the subject, sums up the main stages of this history in an article written for this edition of Electra. However, we are not investigating curiosity just for historical erudition. We cannot ignore its relationship with science (in two articles: one by Olga Pombo, who has published a vast body of work on encyclopaedias and the philosophy of science, and the other by the astronomer Pedro Russo). Our starting point could perhaps be based on the following question: how can we talk about curiosity today, at a time when it is rarely evoked, and it can almost be considered no longer present? Has it been erased? Has it lost the strength that made it the driving force behind reason and spurred mankind on towards the future? Or has it been diluted in other intellectual forces that are more suited to current forms of circulation and the quest for knowledge?

Any elucidatory answer to these questions needs to make reference to our current reality, as we are immersed in an environment of input overload (of information, communication, cultural assets). There is always someone or something to fill the free time that curiosity requires. In the midst of such profusion and abundance, we have to carve out our own space and time so that curiosity can thrive again. Thales of Miletus was a curious man. This scientist with his head in the clouds, oblivious to the practical, pragmatic or immediate, was one day so distracted while walking and gazing at the stars that he fell down a well, causing his Thracian slave to laugh out loud. Blumenberg, who perceived curiosity as the disinterested contemplation of the world, regarded Thales of Miletus as a proto-philosopher.

Curiosity needs an empty space to fill. This is why it is associated with the idea of imagination. Today, thanks to all the new digital technologies, the range of choice has grown to such an extent that there is now a new and significant kind of crisis in the diagnosis of the age: the attention crisis. Attention is not the same as curiosity, though one involves the other as there is no attention without curiosity, and all curiosity stimulates attention. This so-called ‘attention crisis’ in modern society is the result of not having enough time to consume what comes to us without needing to search or exercise our curiosity. There is never enough time to watch, read or listen to everything. Our attention therefore wanders and our mental abilities buckle when faced with input overload and the profusion of media. Now that attention is in such short supply, it has become a precious asset that needs to be recaptured. The ways of attracting our attention, in these times when it is so highly dispersed, are far more sophisticated and intrusive than they were when our attention resources had not reached their current state of exasperation. A new economy has thus been born – the attention economy. And this economy is trying to manage our curiosity drivers.

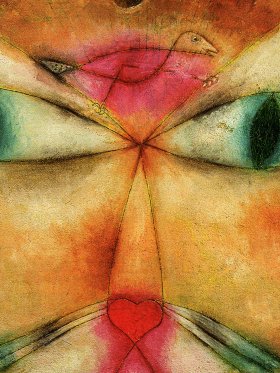

Baudelaire was the modern poet par excellence who realised what ‘modern life’ was really like in the great 19th-century metropolis of Paris. He was perhaps the first person to understand the phenomena that were beginning to appear. The dandy, one of Baudelaire’s figures, cultivated the image of a man who was impervious to everything and not at all driven by curiosity; indeed, it was he that attracted curious looks from others. Baudelaire was also the poet whose poetry evoked an awareness that his condition was no longer that of the old-fashioned poet with an aura, and that there were no longer readers for his poetry. It is true that things were not yet like they are today, where authors sometimes outnumber readers. But Baudelaire, a writer of ‘aesthetic curiosities’, an art critic in the age of salons, was a poet of ‘literary curiosities’. It is precisely under the banner of Baudelaire that Lionel Ruffel writes here in the defence of literature that does not conform to the canons of gender, that breaks rules and moulds, and that cultivates strangeness as a feature. We are also invited to consider another meaning of ‘curiosity’. It is no longer the theoretical curiosity that Modernity rehabilitated and turned into an epistemological driver, a passion for science and know-how; it is rather an idea of curiosity as a kind of almost indefinable quality of everything that inspires awe. In this case, curious means something strange or even exotic.

This takes us back to the curio cabinets and personal collections of items or artworks that were the forebears of museums. Federico Ferrari writes about these, showing us how modern museums are institutions of curiosity. Now that one of the great drivers of tourism has become the pleasure of recognition and not the curiosity of discovery, museums are perhaps still the perfect places for paying tribute to curiosity, in an age when the spirit of curiosity has weakened, like organs or limbs that have ceased to function and become idle or withered.

*Translated by Wendy Graça

Share article