When Pedro Costa talks about his work, his musings carry the same eloquence and force as his films. Claiming the luxury of time and a scarcity of means, he has created cinematic works capable of elevating a neighbourhood from the outskirts of Lisbon to universal recognition, and of giving an epic or tragic dimension to people (not exactly characters) who embody words, experiences and memories more valuable than any well-crafted screenplay. This cinema, so consubstantial with life and the places haunted by the tragically or epically grandiose people who emerge from it (of note are Vanda, Ventura, Vitalina, singular creators of worlds), has generated admiration and even a cult following in numerous countries around the world. There is a foreign image of contemporary Portuguese cinema that owes a lot to Pedro Costa’s films and to the prestige, praise, enthusiasm and accolades that his films have garnered. This is undoubtedly ‘minority’ cinema, whose language the consumers of blockbusters will find difficult to understand. According to the auteur in this interview, in it we can find a disappearing art.

Pedro Costa is an ‘auteur’, but to a far greater degree than that alluded to by the notion of ‘film d’auteur’. His films overflow with reality and are populated by people who emerge as exemplary figures of our age. Despite following his own unique and undefinable path, Costa has garnered international prestige and reputation as well as numerous international awards, and has greatly contributed to the spread of ‘Portuguese cinema’. This interview examines his work and everything it involves.

ANTÓNIO GUERREIRO The further we explore your path as a filmmaker, the more we have the feeling that you come from a place that is not the place of cinema, or, at least, of its current prevalent recognisable norms, and that you look more to painting and literature instead. How did you get into cinema?

PEDRO COSTA That’s an unusual observation. I feel increasingly close to the pre-history of cinema. For me, film has always been important – an axis around which everything else turns. I don’t mean I was ever a great film buff, but even today, I need film to help me watch and listen better. I love to watch and listen to film. I love making. And I think that I only had the experience of other arts, and I only read, listened and could fully experience the so-called sensitive world thanks to cinema. Film enabled me to read better. Well, perhaps music is an exception, but music is such a huge exception anyway, right? We live in music from the moment we are born… And I can’t forget my experience at Lisbon’s Theatre and Film School, where I met people such as João Bénard da Costa, João Miguel Fernandes Jorge and, most importantly, António Reis. The school hadn't yet become institutionalised, the teachers were approachable, and it was a period of great camaraderie and passion. These were years marked by insolence and absolute certainty. I know, for example, that my discovery of António Reis’ Trás-os-Montes reconciled me with this country that I abhorred. I was extremely lucky that my years as a student coincided with the years of the Revolution, or rather, with the years of the failure of the Revolution. It was then that I started to put together the pieces that made up my life. It was in those hot summers between 1974 and 1980 that I started to watch films in earnest, as well as to listen to music, read poetry, study paintings, think and engage politically every day in the streets. And in that turmoil, all of the arts resonated and merged with each other. It was at that time that my interests were established, and they’ve hardly changed until today. Classic Hollywood cinema, the great retrospectives of Mizoguchi, Ozu, Bresson, Ford and Hawks, organised by João Bénard at Gulbenkian, Straub and Huillet, and Jean-Luc Godard. But, for me, film has always been a lonely activity, for better or for worse. Music was collective, it was being with friends, in bedrooms and in the streets, and at that time I was militantly in the street. Early on, I knew what side I was on, both in the street and in film. It was a time of excitement, admiration, even madness…

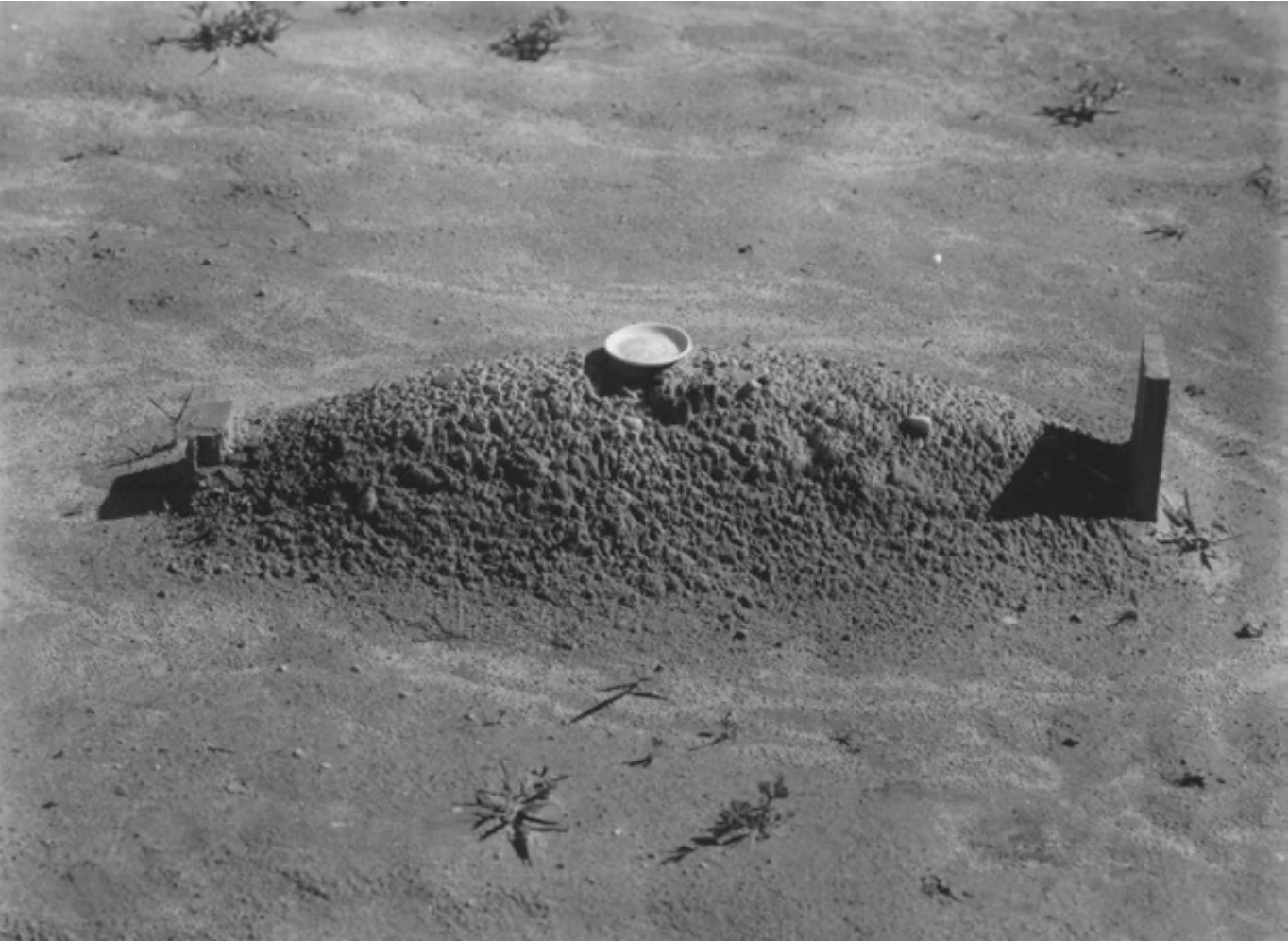

Walker Evans, Child’s Grave, Hale County, Alabama, 1936

© Photo: Scala, Florence / The Museum of Modern Art, New York

"Nowadays, cinema is either on the walls of museums and galleries or has become a juvenile device worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The cinema that has entered the museums for aesthetic or formal reasons will certainly end up devouring itself in vacuity and artifice."

AG My previous question suggested that your films have gradually incorporated other media, painting, for instance, in the search for purity.

PC don’t know if ‘purity’ is the right word. Cinema is my centre, but it’s not an absolute. Cinema is work. I only know that work produces more work, it doesn’t produce cinema or art. In other words, cinema is not an end in itself, a film has to lead to something else. Making a film just for the sake of it isn’t enough, right? I wouldn’t go to so much trouble otherwise… At least, that’s the direction that I try to follow and pass on to the people who work with me. In our case, that might mean devoting time to getting to know, not the characters, but the actual people with whom we’re filming. And experiencing or studying the places where we’re going to be shooting. We need to familiarise ourselves with a neighbourhood’s economy and routines if we’re going to get one, two, or three decent scenes. We need to spend time navigating the bureaucratic hell and looking after the health of our collaborators and actors. For conventionally produced cinema – cinema that is more concerned with profits and the refrain ‘time is money’ – all of this is wasted time, when, in fact, this time serves the film. I believe that we spend at least as much time dealing with so-called production issues as with so-called artistic ones. My team and I all strive for the same goal: making do with little, finding ways of concentrating and reducing. How can we recreate so many visual memories through light and sound, but without wasting or inflating costs? By using scraps, what’s left in skips, by being part of a collective movement. After all, aren’t we working with the remainders of memories, houses, people? More and more, I have the feeling that we should take a few steps back. In order to make films I have to centre myself. And, contrary to what you said, centering myself means concentrating on film. But, I repeat, concentrating on film as a possible inquiry into a given situation or reality. The problem is that, for me, aesthetics always come first, which is why I am often accused of being overtly referential and reverential towards the ‘art of cinema’.

[...]

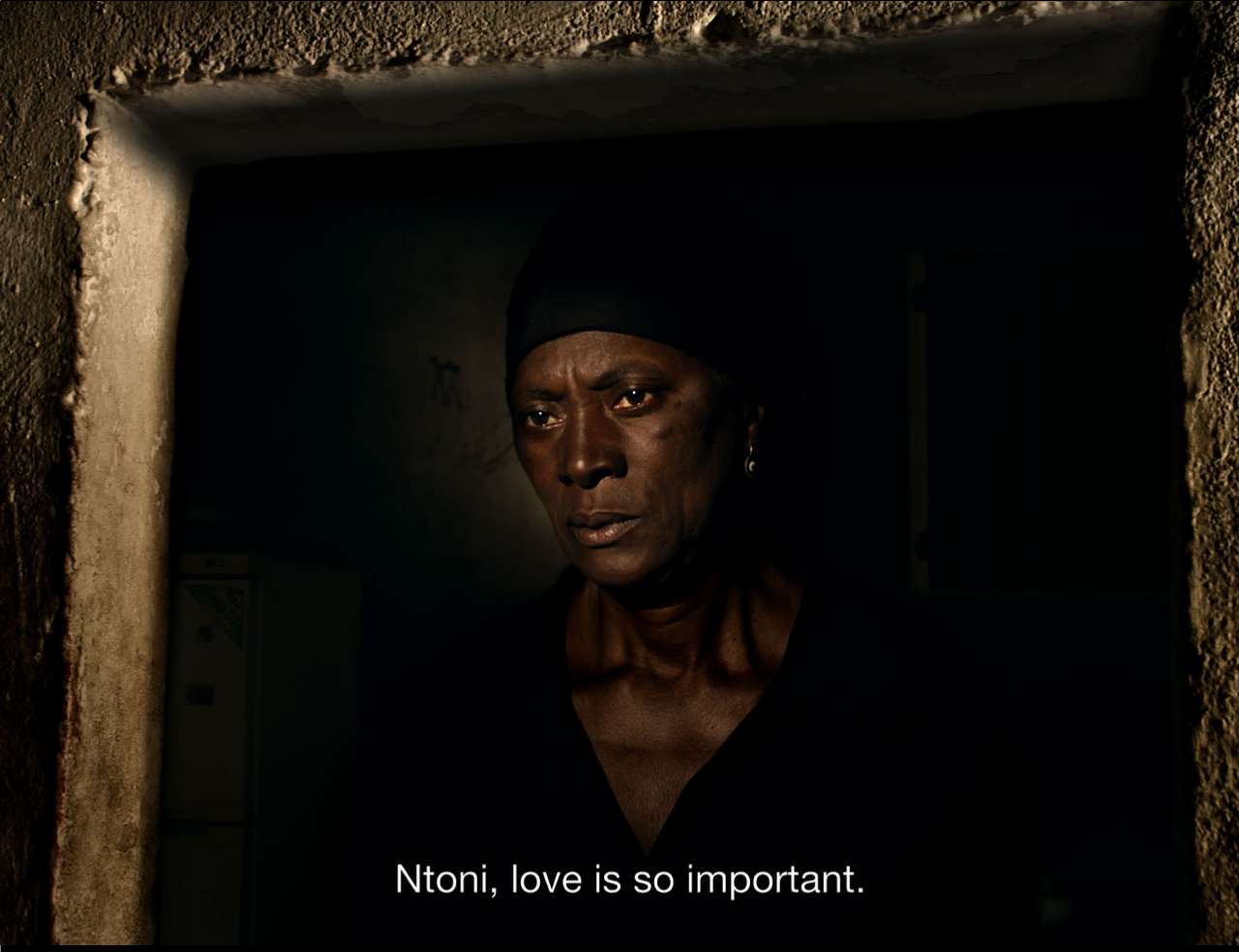

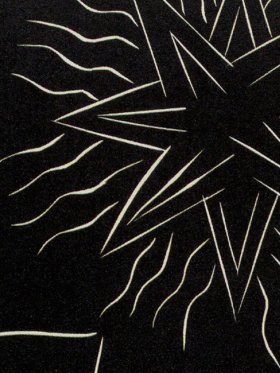

Vitalina Varela, 2019

© Pedro Costa

Share article