And so an age-old word was bestowed upon a modern device constructed by our curiosity that left Earth to satisfy the curious human desire for knowledge of the unknown and to answer questions – both fascinating and disturbing – about the universe and its many worlds, crossing the eternal silence of the infinite spaces that terrified Pascal.

Giving this name to a rover that sent selfies back to Earth was an addition and tribute to the long life of curiosity (of the word itself and of what it has been and meant), updating and universalising a history that is far less simple and far less stable than first appearances might suggest. And it is in the contradictory complexity of this unstable and fluctuating history that we find its most potent and profound meaning. It is these variations and changes over the ages that provide us with the basis for attempting to understand something so crucial to our time.

Curiosity is an immensely powerful motive in mythology, literature, science, philosophy, politics, and in the lives of men and women. It triggers research, investigation, discovery, knowledge, imagination, creation, snooping, transgression, sin, risk, action and progress.

From occult knowledge to the geography of travel (‘This is tiresome, but curiosity triumphs over all: it is perhaps the chief requisite in a traveller…’, Marquis de Custine); from sexual voyeurism (‘Philosophy in the Bedroom seeks the admiration of the curious….’, Marquis de Sade, and Casanova’s The Story of My Life – a tale of curiosity and a telling of curiosities) to scientific investigation; from the bag of winds that Aeolus gave to Ulysses to Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, and from Archimedes’ ‘Eureka!’ to Hamlet’s ‘To be or not to be, that is the question’.

From the questions of children to philosophical inquiry; from the tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden, which tempted Adam and Eve, to Flaubert (‘Love, after all, is only a superior kind of curiosity, an appetite for the unknown that makes you bare your breast and plunge headlong into the storm’); from the Faust of Goethe to the Faust of Fernando Pessoa; from Lewis Carroll to Oscar Wilde (‘The public have an insatiable curiosity to know everything, except what is worth knowing’).

From anthropological surveys to historical heuristics; from Pandora’s box to D’Alembert and Diderot’s Encyclopaedia; from the inscription ‘Know Thyself’ at the temple at Delphi, which Socrates made his own, to Montaigne’s ‘What do I know?’; from Thales of Miletus to Nietzsche (curiosity and courage); from Kafka (‘he was interested in everything new, up-to-date, technological, in the beginnings of cinema, […] he followed modern developments with a tireless curiosity’, Max Brod) to Proust (‘Amorous curiosity is like the curiosity aroused in us by the names of places, perpetually disappointed, it revives and remains for ever insatiable’).

From Icarus and his fatal flight, to Terence (‘I am human, I consider nothing human alien to me’); from Plutarch to Seneca and to Spinoza and his expulsion; from Saint Augustine to Saint Thomas Aquinas (the opposition between studiositas and curiositas); from Hobbes (‘Desire, to know why, and how, curiosity’) to Heidegger; from Aristotle to Jules Verne; from Pascal (‘Curiosity is only vanity. Most frequently we wish not to know, but to talk’) to Sartre.

From David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature to Einstein’s Theory of Relativity (‘I have no special talents, I am only passionately curious’); from cabinets of curiosity to André Breton and Marcel Duchamp; from Cicero (‘Without doubt, the indiscriminate desire to know everything is the mark of curiosity’) to Anatole France (‘Curiosity arouses desire even more than the memory of pleasure’); from King Shahryar of The Arabian Nights to the Letter of Pêro Vaz de Caminha (News of the Discovery).

From all this to all that and as far as one can imagine, it is curiosity that transports us and drives us.

Words speak for themselves and words speak of themselves. The word curiosity, in its etymological origin (from the Latin curiositas), is linked to curios and curia and carries within it the idea of caring and curing. Yet, over time, this initial positive idea of active philanthropy becomes a negative one of adverse misanthropy.

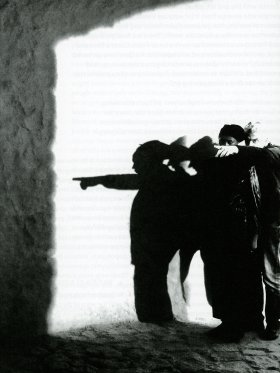

Throughout Classical Antiquity, curiosity was savagely attacked by many writers and defended by few. Curious people became seen as snoopers intent on discovering secrets in order to do harm, demean, or spread (mis)information. They were even mistaken for spies. Curiosity’s unfortunate reputation has been passed down to us. There is a French adage that says that curiosity is an ugly defect. And there is an English proverb that reminds us that ‘curiosity killed the cat’. To this day, we speak of good and bad curiosity.

Curiosity does indeed consist of many curiosities. It is beginning, middle and end: impulse of the subject, movement towards the object and satisfaction with itself. There is curiosity that is intellectual and physical, about ideas and about perceptions, mental and sensory (each sense has its curiosity and there is one that syncretises them), voluntary and involuntary, about contemplation and about action, about feelings and about imagination. There is curiosity about the visible and the invisible, the conscious and the unconscious, good and bad, life and death, individual and collective, profound and superficial, interior and exterior, discreet and indiscreet, laborious and idle. There is curiosity that is Apollonian and Dionysian, mythical and mystical, nomadic and sedentary, theoretical and practical, microscopic and macroscopic, temporal and spatial, about near and far, the past and the future, agitated and serene, systematic and wild, focussed and aimless.

In his very personal history of Curiosity, in which he uses Dante as a guide, just as Dante used Virgil as a guide in his Divine Comedy, Alberto Manguel gives all 17 chapters a question as a title (‘What Is Curiosity?’ ‘What Do We Want to Know?’; What Is Language?’, etc). Manguel reminds us:

Share article