It is curious that so little has been written about curiosity. Aristotle’s Metaphysics opens with a succinct statement on curiosity – ‘All men by nature desire to know’ – and David Hume ends Book II of A Treatise of Human Nature with a section titled ‘Of Curiosity, Or The Love of Truth’. Saint Augustine, too, dedicates an entire chapter (X-35) of Confessions to ‘temptation’, while the aim of Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie is to ‘cover everything related to human curiosity’ (IV: 577-578). It is also true that one of Flaubert’s most dazzling novels is entirely dedicated to portraying the excesses, adventures and outlandish incidents sparked by the curiosity – elevated to a passion – of his delightful characters Bouvard and Pécuchet.

Yet, other than these and a few other notable episodes, and other than the odd, frequently circumstantial, reference in texts by authors ranging from Tertullian to Einstein, Seneca to Montesquieu, and Kepler to Sigmund Freud, texts on curiosity – studies that attempt to address this universal desire to know – are surprisingly few and far between.1

It is as if there has been insufficient curiosity to carefully and doggedly consider that thirst we call curiosity. Or perhaps it is the case that curiosity belongs to a class of concepts that are too vulgar, trivial, humble, and so elusive and widespread that, for this very reason, they resist – or are even, perhaps, unsuited to – theorisation.

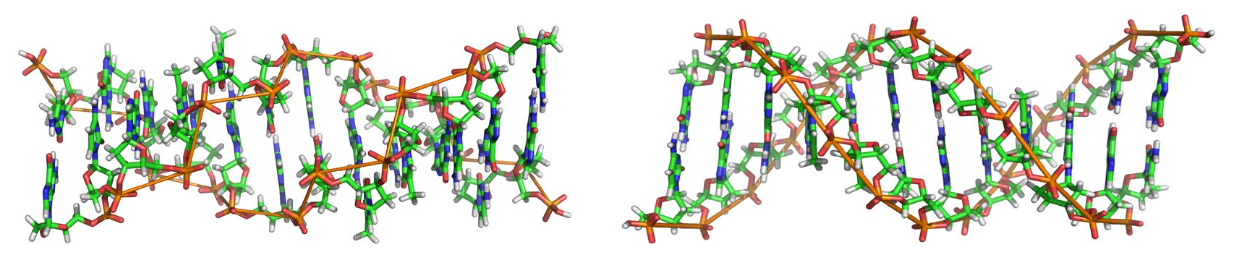

Yet we are all curious without even thinking about it. This is as true of children, whose curiosity is supposedly sparked at school and proverbially repressed at home, as it is of scientists, regarded as those in whom this virtue is heightened, and of men and women of all ages and circumstances who may suddenly be seized by an imprudent desire to get to the heart of facts, events, opinions or theories.

Share article