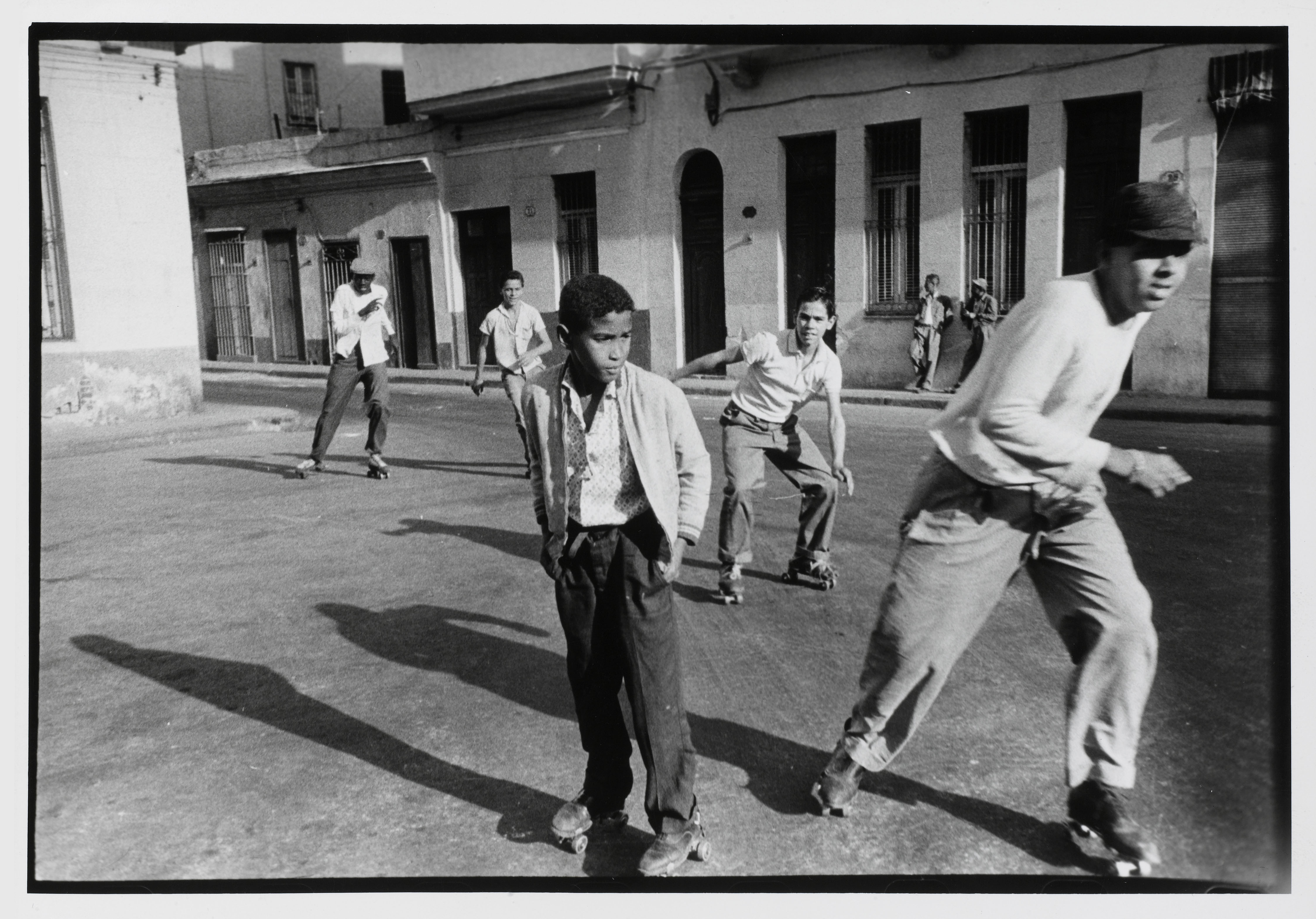

We wanted someone to move us forward and we believed we were travelling from one place to another, but in fact, after waiting for so long, all we could do was reach a place we had already come from. Home, school and work were all the same. There’s a time in Cuba when everywhere becomes the same place, where you can move neither forwards nor backwards, trapped in stillness.

And yet, if you walk, it takes longer but you age less. We residents of Havana should have taken notice of the rage that filled us when no bus came for us, and when the buses that passed by were already full. We should have harnessed that rage and ridden it ourselves, transporting ourselves wherever we wanted to go on its rump. Waiting without purpose is an acid which melts the plastic of youth.

I walked along the Malecón, carefully stepping on the damp, slippery moss on the wall. The early morning sun had an eerie effect on things, making them appear prematurely born. They were blurry, as if forcefully snatched from night’s nest.

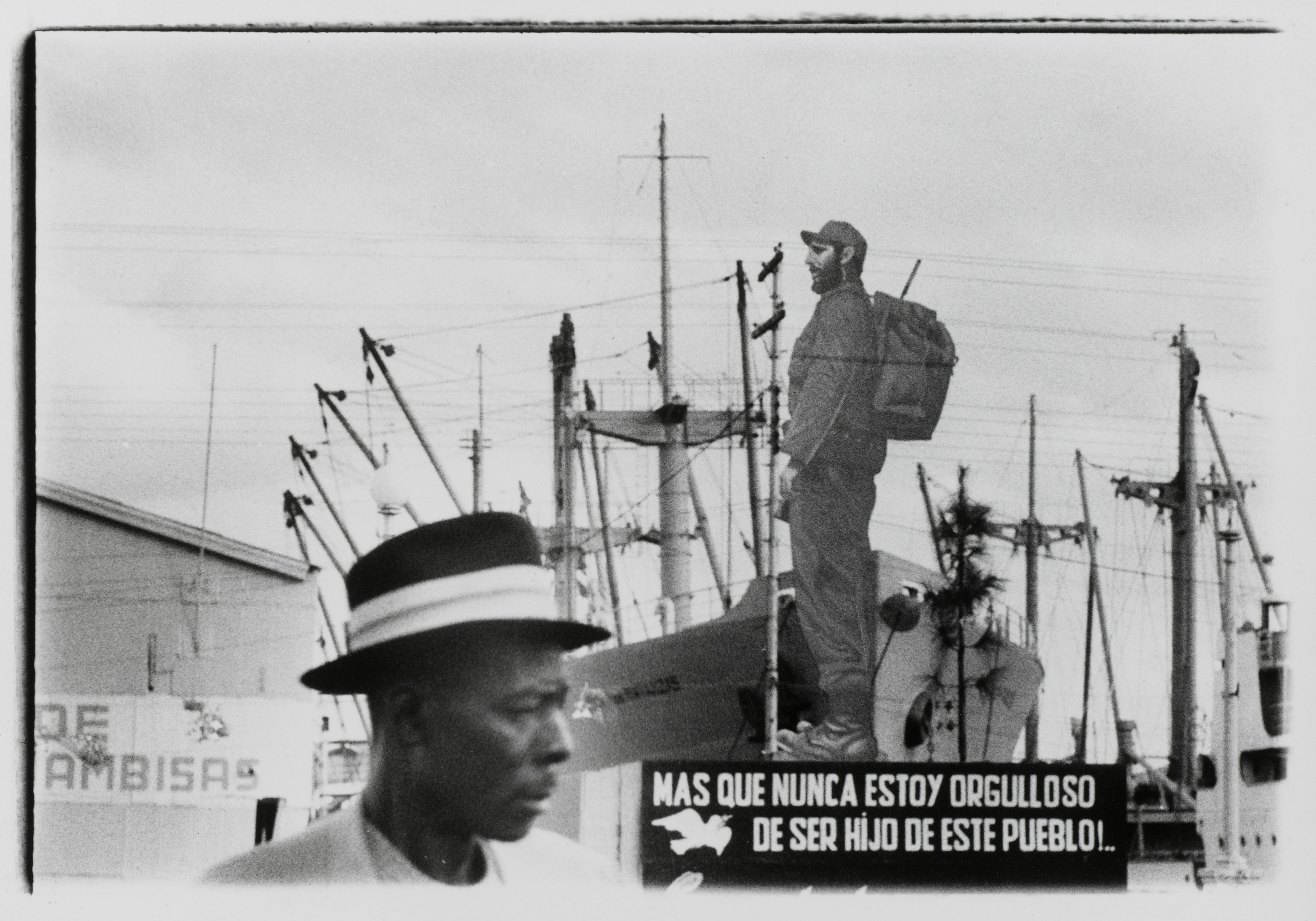

Riding the national rage of exodus, I had left Cuba almost four years earlier and Havana had shrunk every time I returned. More and more, it seemed like a village to me, so docile, so insignificant. I now had an apartment in Mexico City, the mother of all outsized cities, and my perspective had changed. My senses, already elastic, were more permissive, and my idea of proximity now encompassed an infinitely higher number of kilometres. The mainland shows you that on an island, no matter how big it is, there is nothing that isn’t nearby.

Yet the very first time I arrived in Havana, I also began to walk, but I walked because it seemed immense to me; as big as only the city of your dreams can be. It was that place that simmers in your mind for years over the flame of your imagination, that place your mind has escaped to while it waits for your body to arrive so that they can explode together once and for all.

I’d just started university after a life trapped in the provinces, and I walked the main streets following the commotion. I was too afraid to enter the city’s transport network. I felt out of place, unable to understand the internal codes, the traffic signs, the usual routes and shortcuts. So I walked.

That Havana, immense Havana, was the product of survival and scarcity. And this village-like one now was the same. I visited the city to immerse myself in its nights, packed with intense, giddy parties. Seductive parties, with a supreme self-confidence. During the day, Cuba remains communist. It is linear, exhausting, it sweats, it squeezes you, and even people with money find it difficult to get used to. But the night is more and more neoliberal, although it too squeezes you and makes you sweat.

In a sense, day represents the past and night foreshadows the future, the eagerness for an escape without needless effort, a gap through which to slip without fleeing. The country moves between these two impossible times, with nothing appearing to happen in its real time. All of the latest news, for example, about hunger or the scarcity of products in Cuban shops, has already happened.

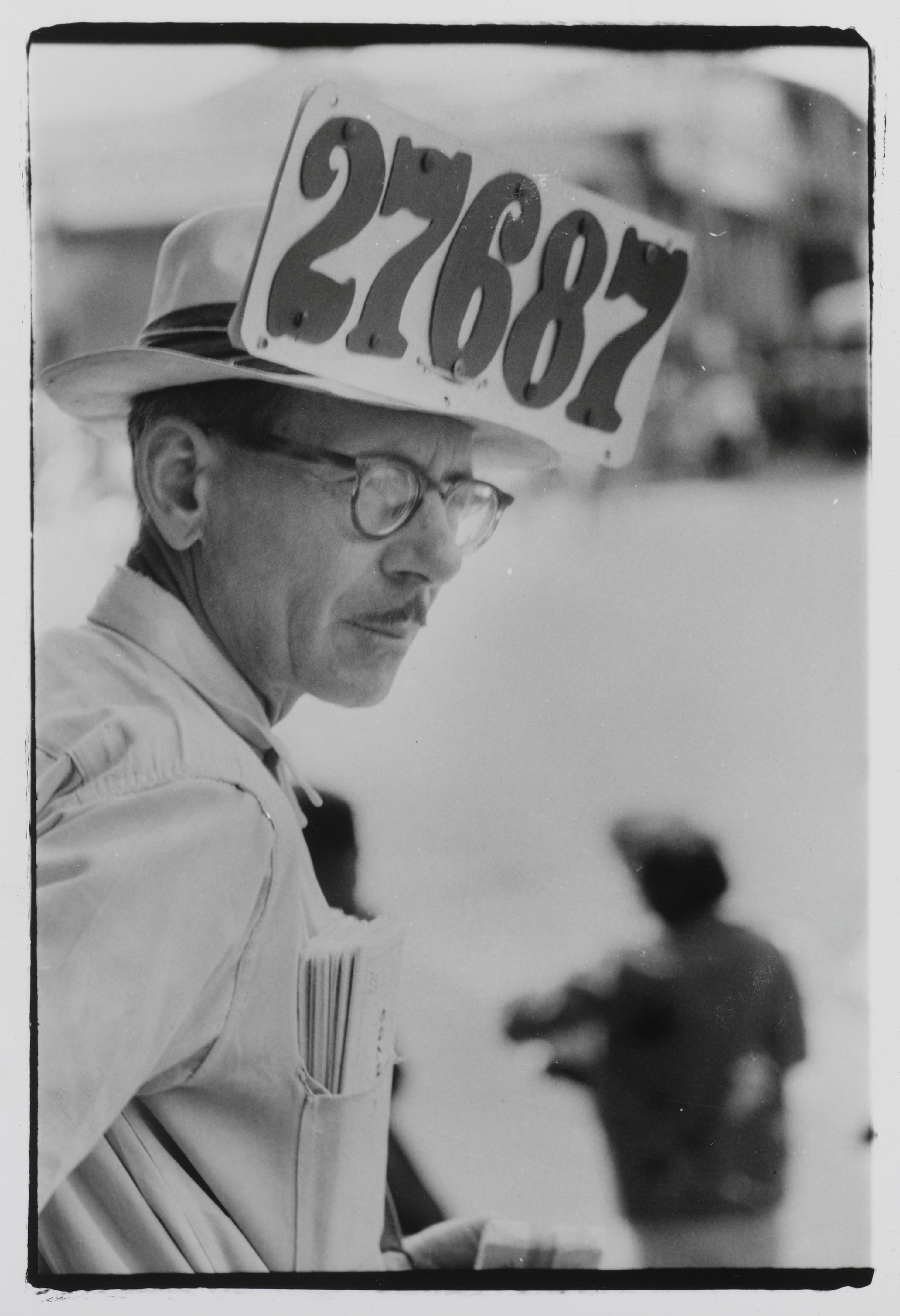

The night teems with medium-sized private businesses built on a conservative ideology, which are now permitted in the city. They are the moles on the skin of this state capitalism, emerging like a decaffeinated advance party onto the landscape of national Stalinism, and revealing the colour of the only other skin that could lie beneath this rubble.

With their demonstrated success, it is these spaces that most effectively embody the idea that politics is a dull matter to be handled by the Castro regime and the Miami exiles, something no longer required for a good life. Clubs, cultural and recreational centres, art galleries, and disused workshops and warehouses have been transformed into cocktail bars and exhibition venues of different kinds.

The advertising used by these companies sells a series of things which are desired by and apparently accessible to everyone, if we bypass the crux of the system and the social relationships it establishes. This is not dissimilar to what Mark Fisher termed ‘the semiotic excrescences [which] despoil former public spaces’.

Share article