Although resident in France for twenty years, in his novels – his oeuvre already numbers a dozen books – it is as if he still lives in Morocco. Abdellah Taïa, born in the city of Salé in 1973, is an Arab writer who the French like to describe as an example of unruliness. This is an image he despises to some extent, tired of the simplistic manner in which the French, and the West in general, regard the Arab world. His most recalcitrant public gesture occurred in 2006 when he came out as gay in an interview with the Moroccan weekly TelQuel, providing a colourful front page headline: ‘Homosexuel, envers et contre tous’. This story of coming out and the dramatic aspect of it, in the context in which it happened, did not end there. He followed this up some time later with a letter published in the same weekly entitled ‘L’homosexualité expliquée à ma mère’. Meanwhile, his renown in France grew, establishing him as a frequent media commentator, while some of his books achieved major recognition, such as the Prix de Flore-winning The King’s Day (2010). In 2012, his oldest artistic wish came true when he adapted his novel Salvation Army for the big screen. The film was shown at several film festivals, including Venice, in 2013. Highly politicised, instilled with European literature, painting and film (he focused on Fragonard and the 18th-century French libertine novel while studying in Paris), Abdellah Taïa at first sight may give the impression of an uprooted Arab writer who has been Europeanised in every sense. But not so. His voice is that of someone who has remained faithful to the world he first knew and who fights to ensure this world is not reduced to stereotypes and sacrificed on the altar of prejudice and ignorance. Moreover, all of his writing stems from an experience whose strength cannot be reduced to the comfortable and innocuous exercises of narrative fiction. It is this experience, and the way it carries over into his literature, that he talks about in this interview in Paris.

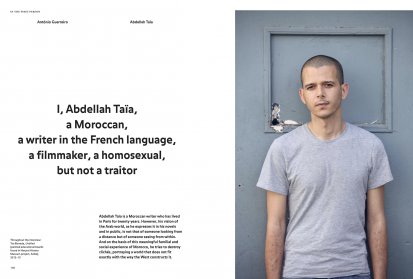

Abdellah Taïa is a Moroccan writer who has lived in Paris for twenty years. However, his vision of the Arab world, as he expresses it in his novels and in public, is not that of someone looking from a distance but of someone seeing from within. And on the basis of this meaningful familial and social experience of Morocco, he tries to destroy clichés, portraying a world that does not fit exactly with the way the West constructs it.

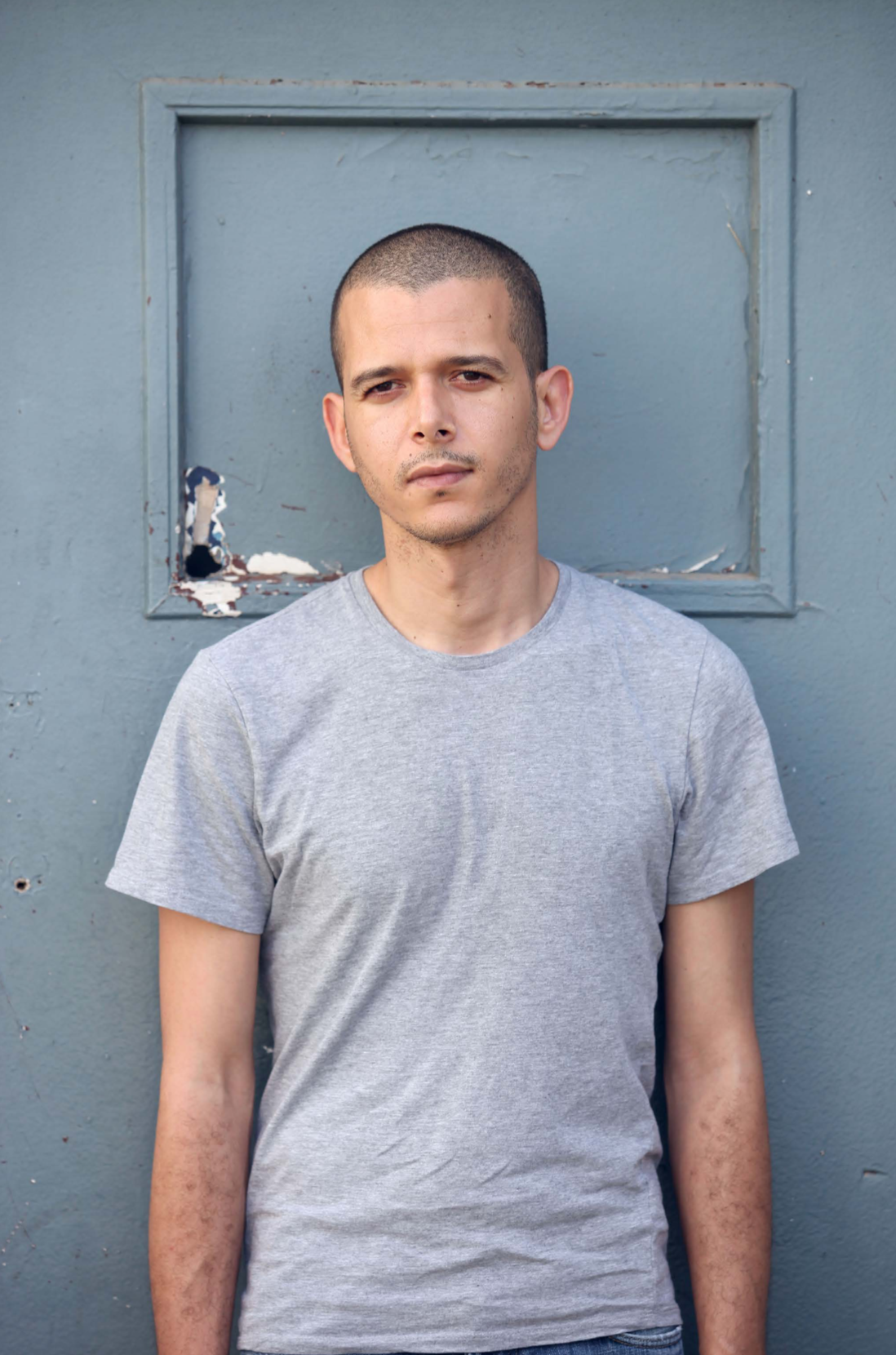

Abdellah Taïa

© Yto Barrada

ANTÓNIO GUERREIRO You arrived in Paris in 1999, you write in French, but Moroccan biographical details always lie at the heart of your novels.

ABDELLAH TAÏA It’s obvious that my writing can only come from my Moroccan roots because I was born in Morocco, in 1973, and lived there for 25 years before coming to Europe. Even if, one day, I decided for some stupid reason to change how I see the world, I wouldn’t be able to, because it’s something that’s created within, even before we’re aware of the way it dwells within us. It’s not just my view of the world; everything I am is Moroccan and Arab-speaking, not Francophone. I was born into a large and very poor family that had to fight constantly to survive. It’s always there; it’s something you can’t forget. You don’t betray your roots just by writing in French.

AG But at the biographical level, you’ve added a second, and long, life in Paris to this Moroccan one. And yet you keep returning to Morocco in your books.

AT You can think of the 20 years I’ve spent in France as, let’s say, a ‘prison sentence’ [laughter]. Could living in a small cell (I actually live in a studio which is like a small cell) for 20 years make me forget, remove from my skin, and my eyes, the indelible traces of what I experienced before, for the first time? Everything I experienced for the first time was in Morocco.

AG So all of that continues to be insurmountable…

AT It wasn’t a conscious decision; it’s something that’s beyond me. It’s not a question of borders and nationality. It’s a question that relates to the way the body is constructed as a memory. And this memory doesn’t come from an intellectual universe; it doesn’t come from what we read or study in school and university. It comes, rather, from a coupling, an osmosis, between the body and the earth, the air and the wind. We have no control over any of this. And everything I do at the artistic level, whether it be literature or film, comes firstly from these places, where we’re unable to intellectualise things, unable to reflect on the dominant intellectual codes of the time, whether these be Western, French or any other. It’s not therefore about being loyal to Morocco or the Moroccans, or of pride in being an Arab; it’s a far more basic question than that.

AG But you use the French language…

AT But that’s out of revenge [laughter]. Post-colonial and social revenge: to escape poverty and to escape the humiliation that I was afflicted by. I use the French language but I don’t speak like those who humiliated us in Morocco: the rich Moroccans and the many French who go there. This thing we call French – the beautiful, extraordinary language of Proust, Molière, Foucault and Barthes – is used by these same French people to humiliate those who don’t speak it well. I don’t have a fascination for the language; all I have is a desire for revenge and to get to those who humiliated me in order to seize their language and change it from the inside.

AG When did you start to become fluent in French?

AT Quite late. Happily for me. I went to a state school in Morocco where all lessons are taught in Arabic. But I decided to study French literature when I was 19 at the Mohammed V University in Rabat and it was there that I discovered that my French was poor and decided to work at it to become fluent. But this came too late to change anything about the way I understand the world and react to it. I had already been moulded by the world. French was just a means to achieve a goal. For me, French, however sublime it may be, is nothing more than a means to an end.

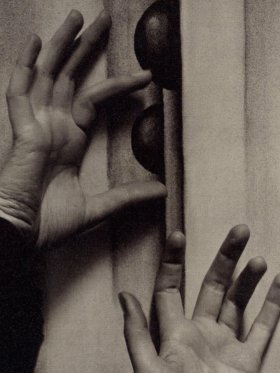

© Yto Barrada

AG At that time, when you began the process of mastering French, did you already have a political awareness of this whole question of language?

AT I had some idea, but things weren’t as clear to me then as they are today. I was a teenager. However, my awareness of the world was the same as my mother’s and I knew the world she lived in, how she manipulated people for a little money, and all that. But this awareness of the world, which is just as important if not more so than the knowledge that comes from books, in all its intellectual forms, is the awareness of survival. In the same way that, as a homosexual, I learnt to identify at a distance those who wanted to rape or insult me, and had to arm myself with rhetorical tools to prevent them from hurting me. This knowledge seems to me to be just as important as the things I learnt later as a student. What I mean is that people, unfortunately, live in a world where the intellectual side of things – what we learn as students – is all important and they therefore oppress those who weren’t fortunate enough to study. As if the way these people reflect on the world, react, struggle and transgress has no value. Only Rimbaud’s transgressions matter. The transgression of people like my mother, a poor and battling woman, is seen as worthless in this world. And that’s something that profoundly shocks me, even today. I think that what made my mother, the struggles she faced, is more impressive than what made Rimbaud or Simone de Beauvoir. Evidently, this judgment only has any value at my level. It’s my job to say how much my mother’s struggle, resistance and transgression are extraordinary. And it’s even more important to say it because I’m gay, which means that this way of understanding the world, of discovering I’m gay in an Arab country and how I can save myself, means I can’t forget what my mother has lived through and what she has done for me. It’s not that she ever talked to me about being gay, but for my survival she did something that was essentially malevolent and wrong rather than correct and well behaved. I think this idea of doing wrong to survive is something that in certain milieus is also inscribed in the character of homosexuals. I found that out from my mother, not Jean Genet.

[...]

*Translated by Chris Foster

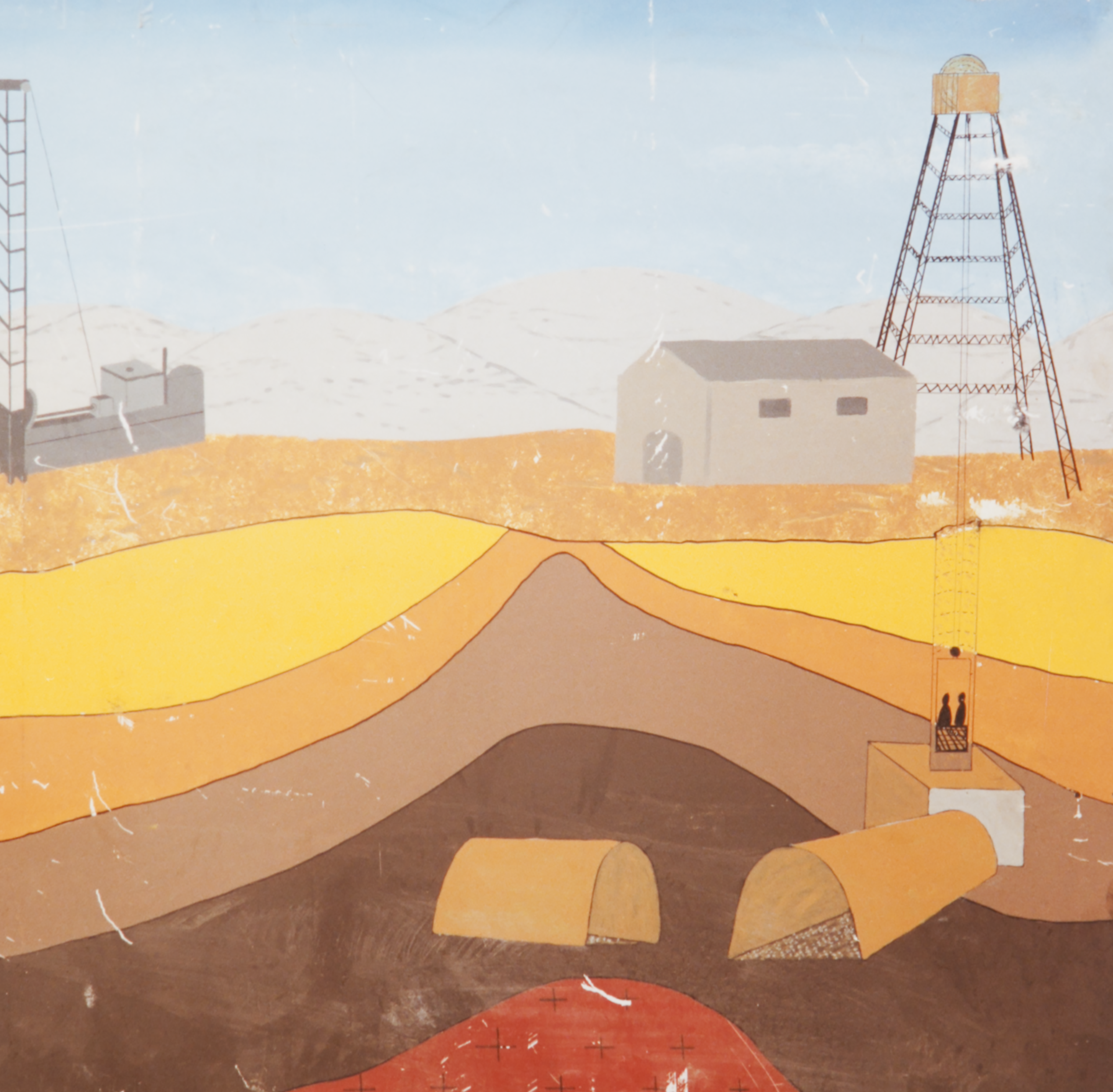

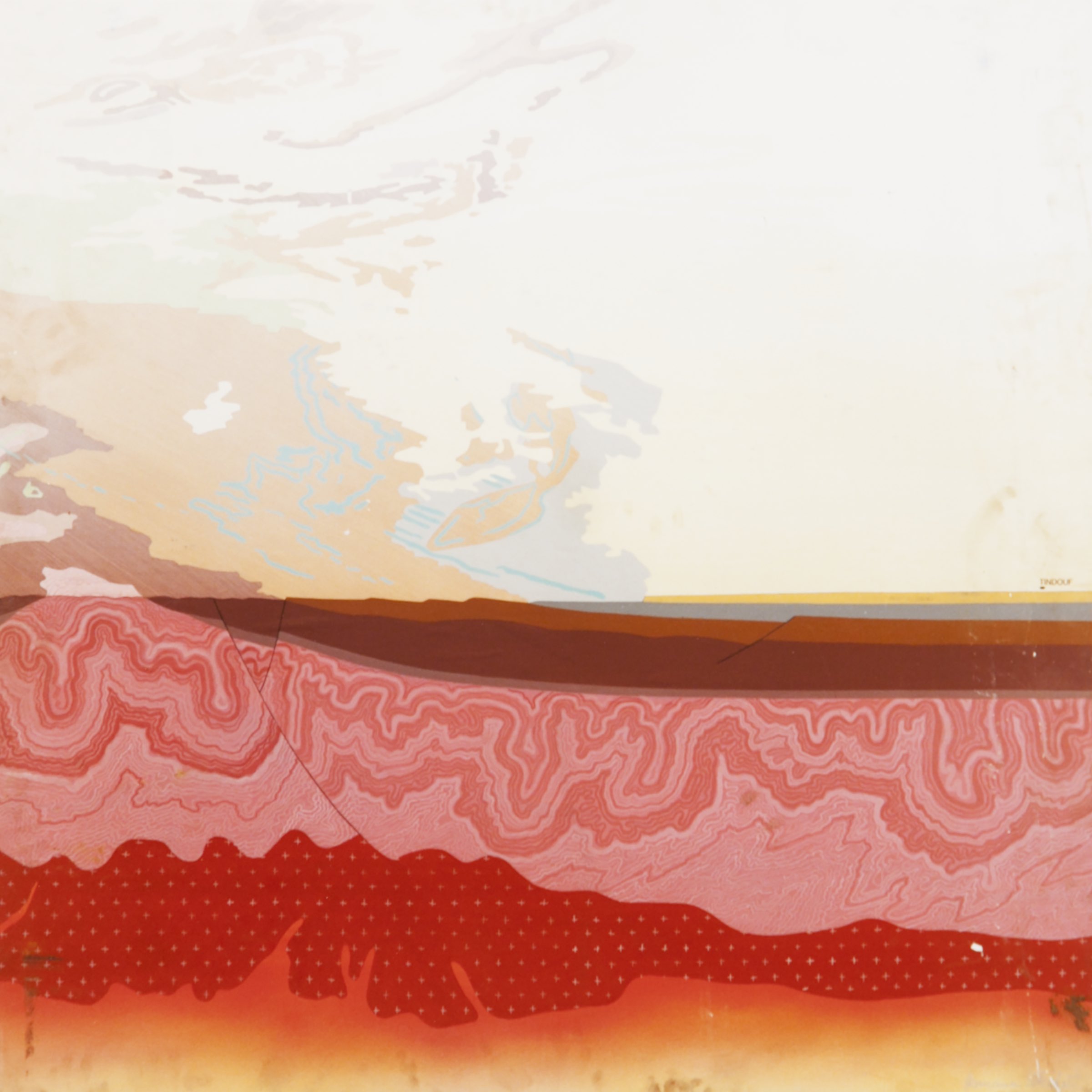

Yto Barrada, Sem título (murais do Museu de História Natural de Azilal, Marrocos), 2015

© Yto Barrada. Cortesia Pace Gallery, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburgo, Beirute; Galerie Polaris, Paris

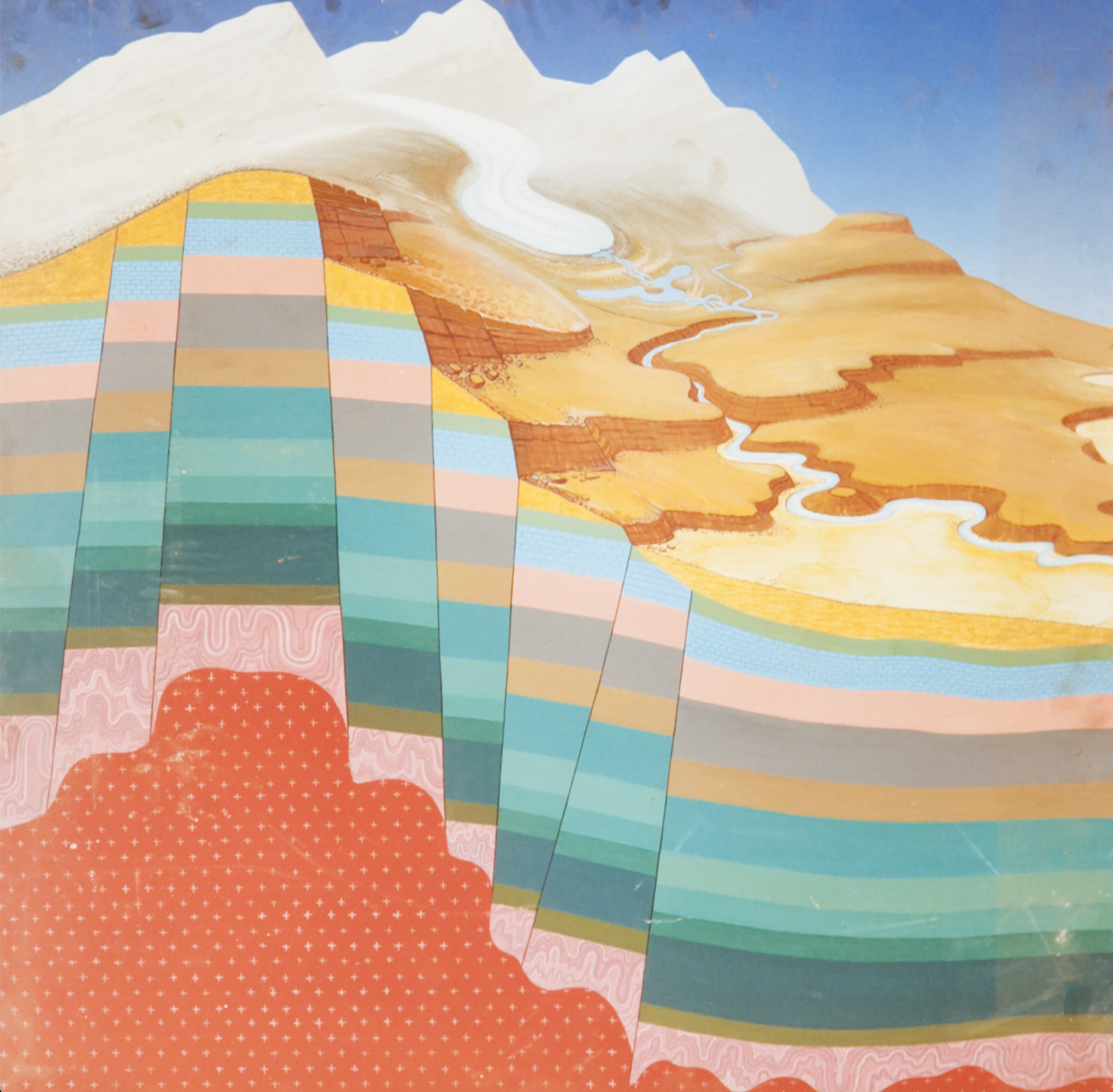

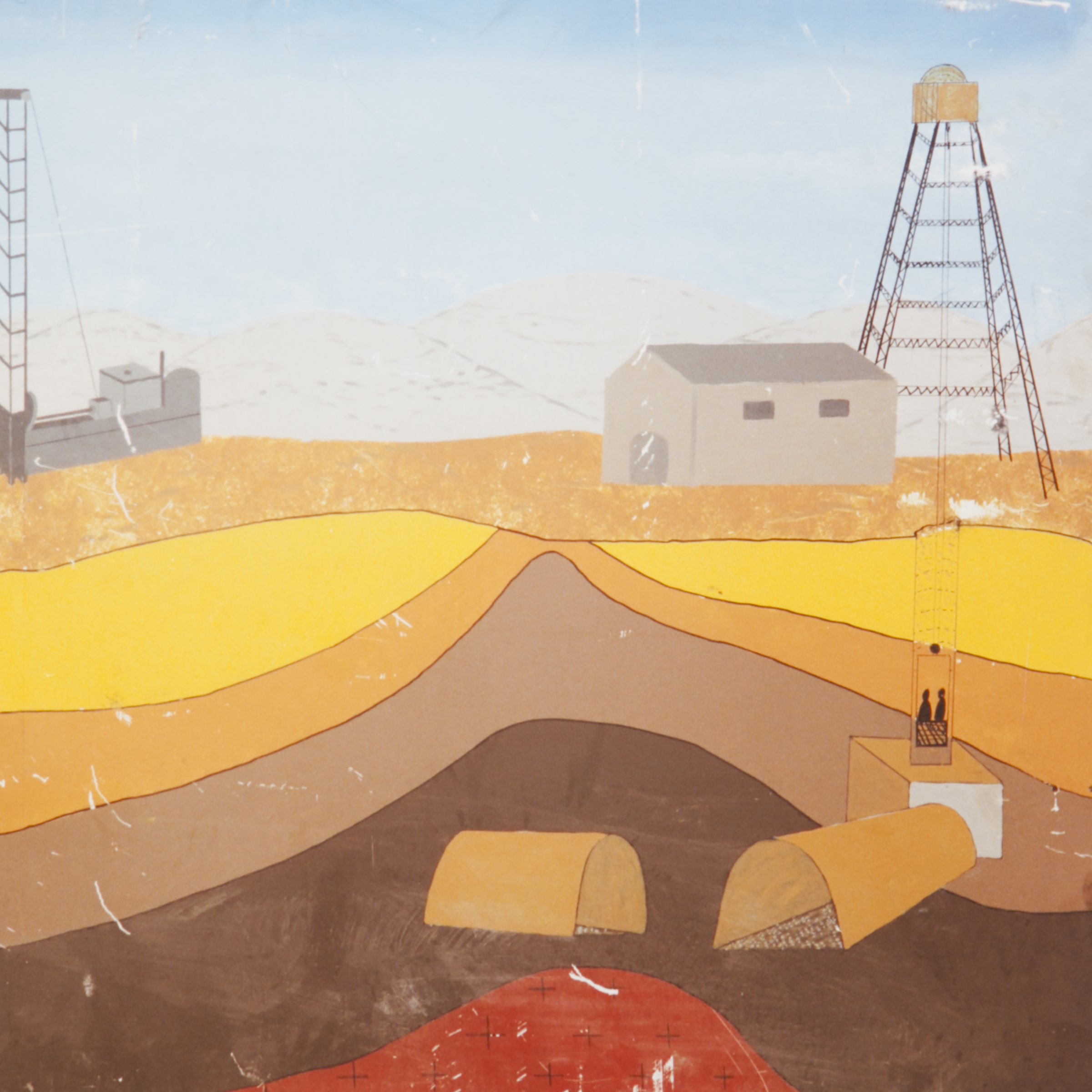

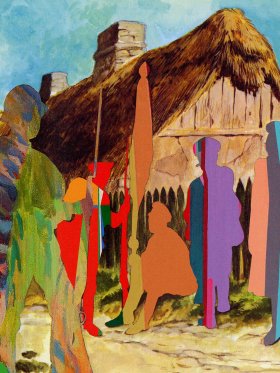

Yto Barrada, Sem título (murais do Museu de História Natural de Azilal, Marrocos), 2015

© Yto Barrada. Cortesia Pace Gallery, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburgo, Beirute; Galerie Polaris, Paris

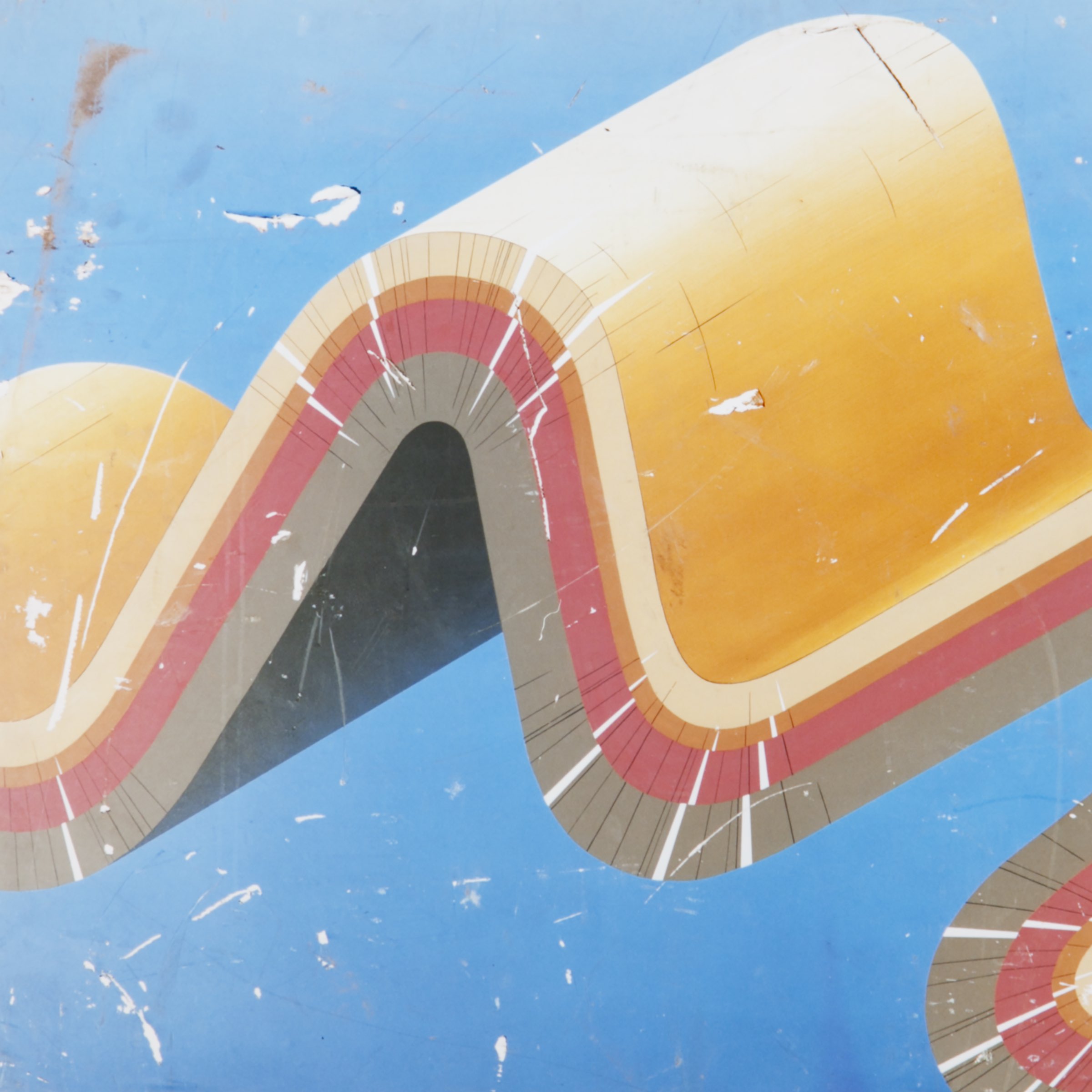

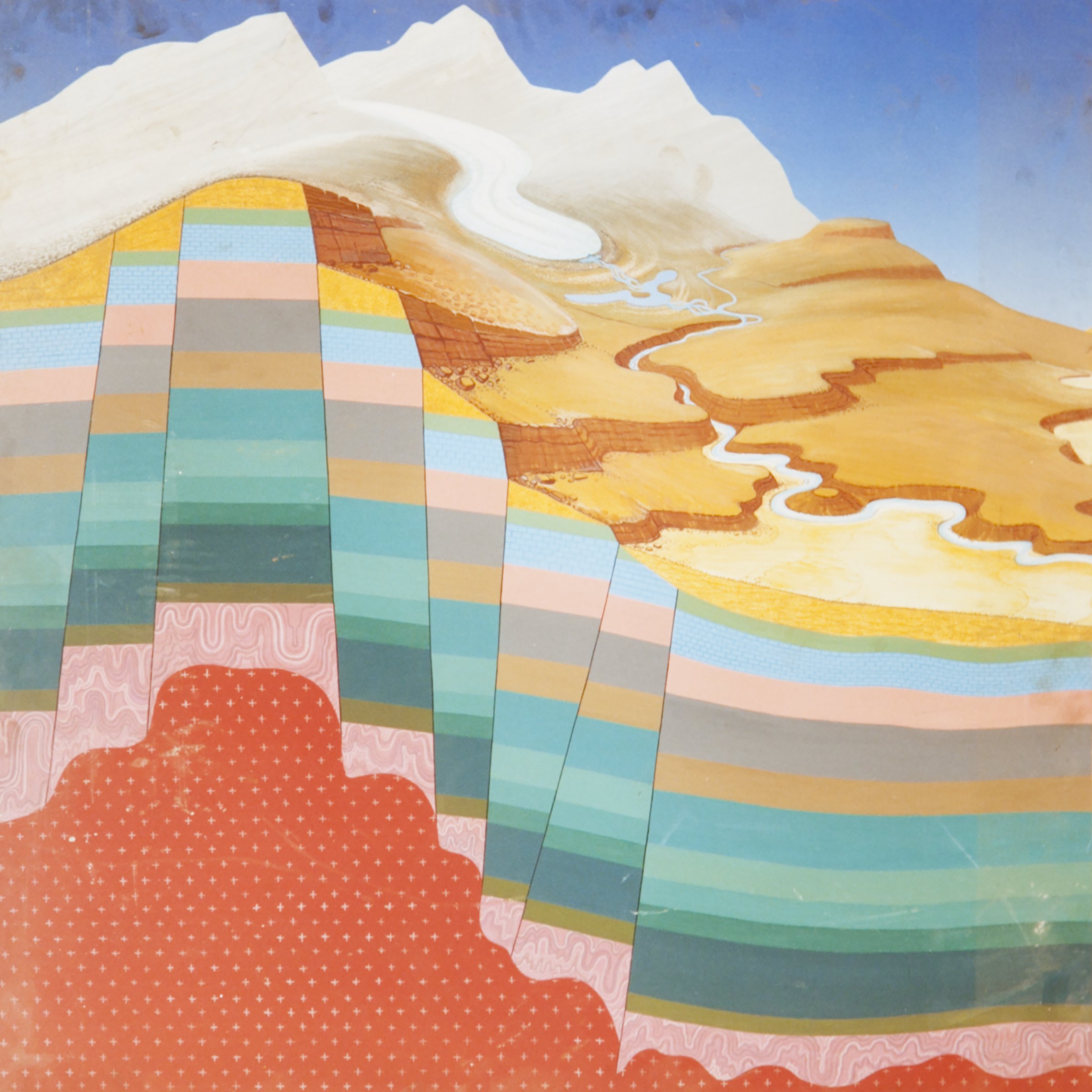

Yto Barrada, Sem título (murais do Museu de História Natural de Azilal, Marrocos), 2015

© Yto Barrada. Cortesia Pace Gallery, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburgo, Beirute; Galerie Polaris, Paris

Yto Barrada, Sem título (murais do Museu de História Natural de Azilal, Marrocos), 2015

© Yto Barrada. Cortesia Pace Gallery, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburgo, Beirute; Galerie Polaris, Paris

Yto Barrada, Sem título (murais do Museu de História Natural de Azilal, Marrocos), 2015

© Yto Barrada. Cortesia Pace Gallery, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburgo, Beirute; Galerie Polaris, Paris

Share article