We can only answer such deep, potent questions in the languages of memory and forgetting. It is as if these two functions of the mathematics of life were the two poles of binary algebra in each of us.

Memory and Forgetting – this is the dual theme of the portfolio in number eight of Electra. It thus relates to the years and their passage from one to another. This is also where the beginning of memory is the end of forgetting, although there are moments in which they touch and mix, like paints and colours. If we look at these two words, we find them laden with commonplaces that have been heaped upon them, making use of them in an operation fertile with clichés, facile ideas and false truths.

From politics to philosophy, medicine to literature, cinema to advertising, journalism to history and economics to sociology, memory and forgetting are mantras and container words that have room for all contents, many of which are unpleasant and pollutant. There is even a musical composition with these words as lyrics that gives kitsch a repetitive, repeated voice. We have to free them from this load and it is under this load that we have to find them.

The Greeks were the masters of all kinds of creation and all kinds of destruction, of all certainties and all scepticisms and of all disguises and all unveilings. As we have already said, we will never be able to escape them. Anyone trying to do so here and now has been caught up by them again – there and then – in an ambush set up on the weary paths of culture.

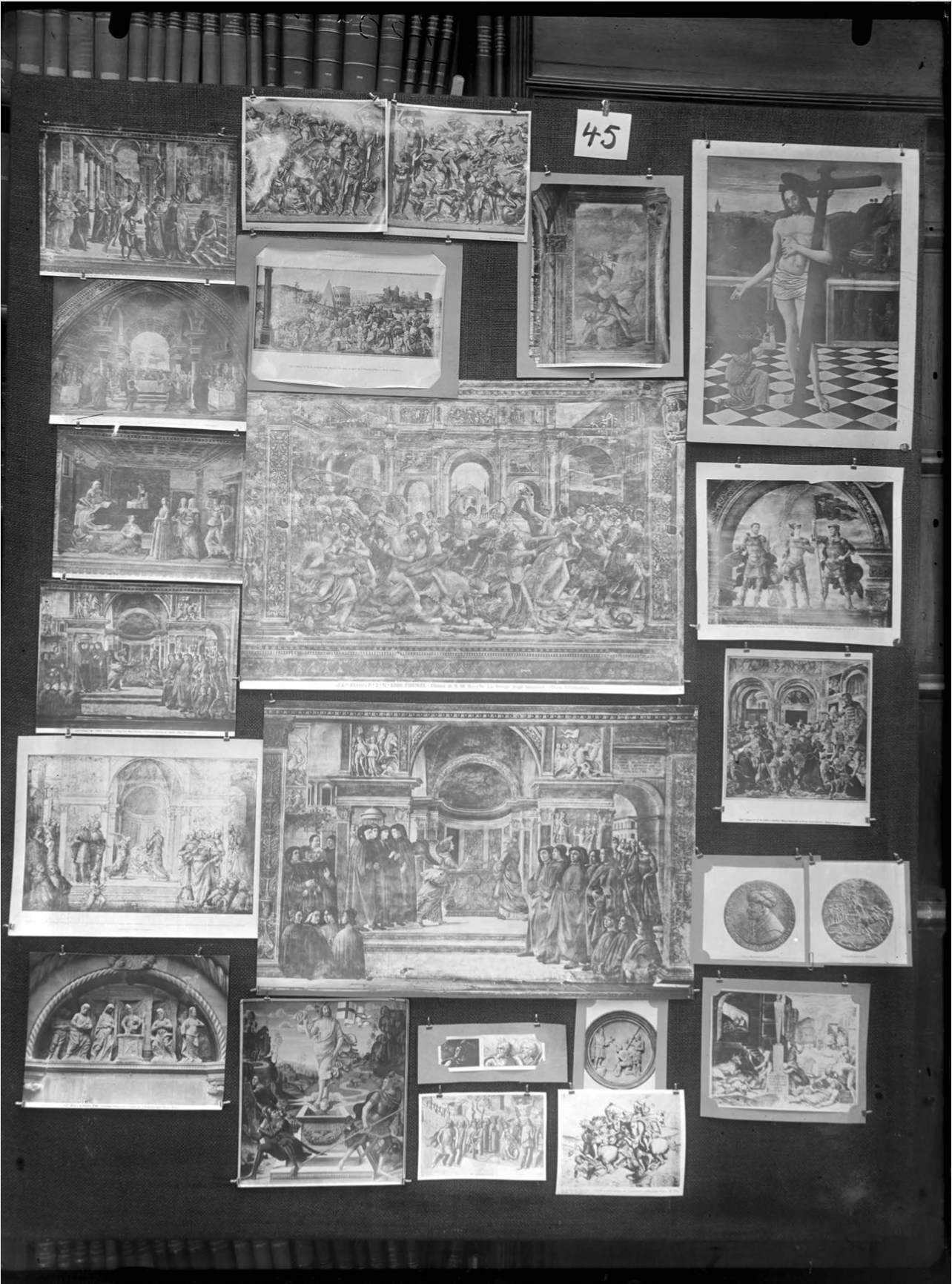

For these initiators and announcers of almost everything, who regarded the beginning of the sea and the end of the mountains with a thought-that-could-see, the Titaness Mnemosyne, whose name Warburg gave to his Atlas, was the goddess of memory. With Zeus as the father, she was the mother of the nine muses who inspire (the verb in the present is a tribute) both arts and sciences.

It is therefore no surprise that the history of our culture has as one of its centres the fight of anamnesis against amnesia and the duel between memory and its oblivion. From Homer to Dante or Milton, from Giotto to Velázquez or Mondrian, from Bach to Beethoven or Mahler, from Galileo to Newton and Einstein, from Paracelsus to Darwin or António Damásio, memory is the flame that burns forgetting and forgetting is the air that lights up memory.

‘In the beginning was the Word (Logos),’ says the Book. That is the Word to which words belong, even those with which the universe was created. ‘God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good. And God divided the light from the darkness. And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night.’ We call memory light (‘in the light of memory’) and we call oblivion darkness (‘in the darkness of oblivion’). And still there are luminous oblivions and murky memories…

If memory is the awareness of time in time, God, whose time is eternity, is the one who never forgets anything. God is the one who never forgets Himself and whose memory coincides with Himself (‘I am who I am’), meaning that His essence agrees with His existence. Eternity and its infinity are His memory with no beginning and no end, omnipresent, omnipotent and omniscient. According to the short story by Jorge Luis Borges, God is ‘Funes the memorious’, the one whose memory pursues him like insomnia with no sleep or forgetting.

Religions make memory their altar, their confessionary and their law-court. There is no sacrament (the Gospel reads that Jesus Christ said, ‘Do this in remembrance of me,’ when introducing the Eucharist) or soul-searching or confession or guilt or penance or absolution or salvation without memory and without forgetting. The solemn Memento of the Liturgy of the Ashes says: Memento, homo, quia pulvis es et in pulverem reverteris (‘Remember, man, that dust thou art, and unto dust thou shalt return’).

These methodical operations of internal heuristics, of subjective hermeneutics and of technology of the ego use memory and forgetting as effective, subtle and meticulous operators of power and transcendence. Sin is a memory that becomes a confession. Absolution is an awareness that becomes forgetting.

If we are talking about this in this way, it is because, in our time more than any other, in everything there is a visible or latent search for a memory of the origin and a discourse about it (archaeology, arkhaîos-logos, literally means discourse of the origin).

From the maieutics and reminiscence of Socrates and Plato to Freud’s psychoanalysis (the return of the repressed); from Rousseau’s to Saint Augustine’s confessions; from Roland Barthes’ allusion to ‘the force of all life: forgetting’ to Kundera of political memory and the lack thereof in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting; from Pierre Nora’s Places of Memory to the teaching of memory by George Steiner; from Paul Ricoeur’s phenomenology of memory to Sebald’s ‘post-memory’, there is a logomachy of these two words and a psychomachy of what they represent.

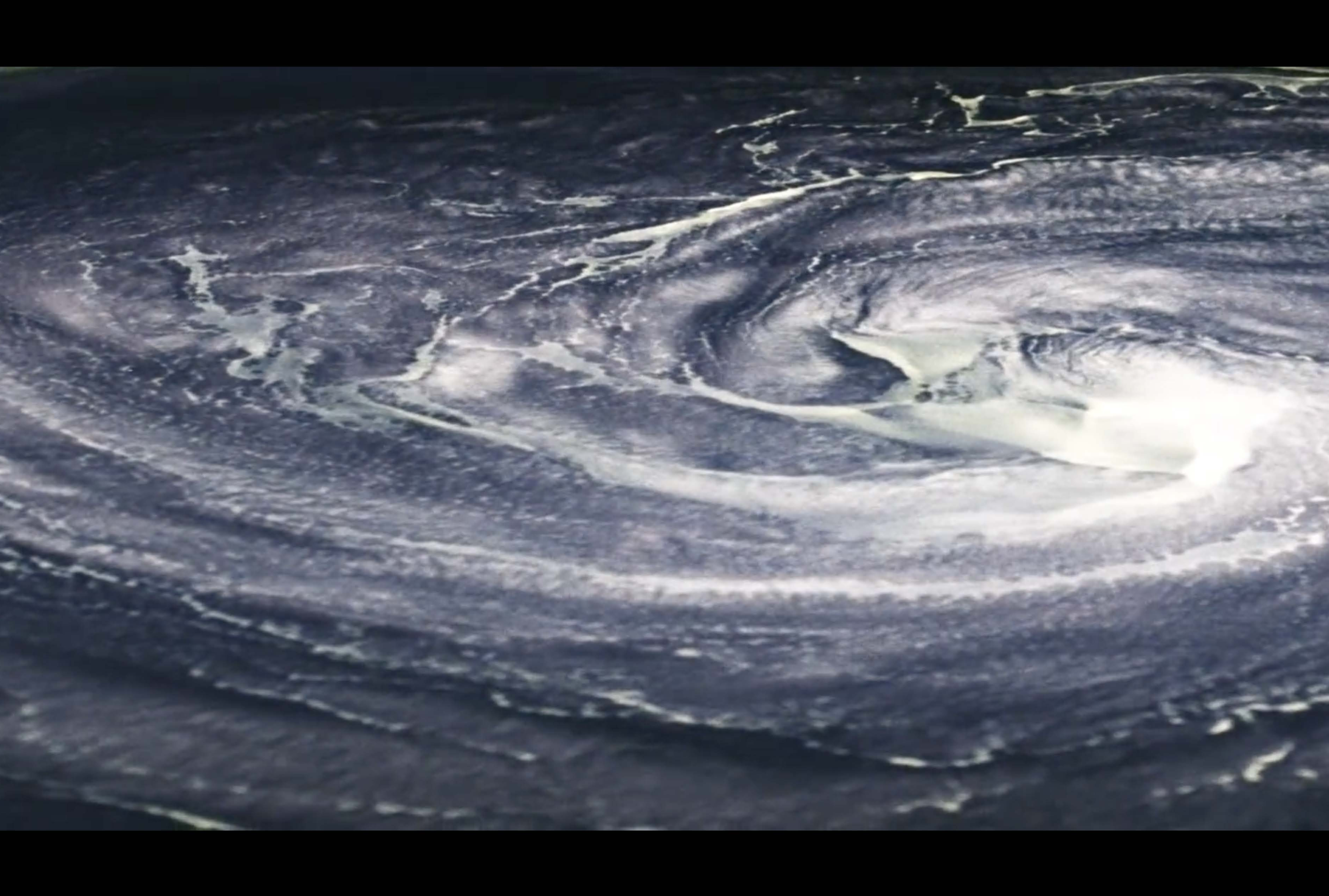

In the 19th century (the great age of historicism, in which photography and cinema also appeared) and the first half of the 20th century, memory and forgetting became a motive that gave thought and art an engine and acceleration. From Nietzsche (Every action requires forgetting) to Bergson (Matter and Memory); from Chateaubriand (Memories from beyond the Grave) to Proust (In Search of Lost Time); from Pessanha (the poem Olvido) to Pessoa (Ser consciente é talvez um esquecimento and Da saudade, esquecimento que se lembra); from Manet (Oublieuse Mémoire: Le Processus de Rémanence dans la Production Picturale de Manet is the title of an essay about him) to Magritte (Memory); from Baudelaire to Walter Benjamin, who in his essay about the poet speaks of the relationship between experience, memory and art as one of the reasons for his work; from Wittgenstein and his distinctions about the connection between mind (‘bringing to mind’), memory and its images to Paul Valéry of ‘memory is the future of the past’; from Picasso (La Mémoire du Regard was said about his work) to Dali (Persistence of Memory); from Hitchcock (Rebecca) to Tarkovsky (Solaris) or Lanzmann (Shoah), memory and forgetting are pitted against each other like gladiators in the circus of life and art.

After the Second World War and the savagery that it involved, the stage of culture acted out the tragedy of memory and forgetting. Totalitarians wanted to surround, censure, control, command and create memory and forgetting. From Hitler’s theories and ravings on the histories of Arians and Jews to the murderous fictions and propaganda inventions from pasts, presents and futures, with events, glories, heroisms and crimes; from Stalin’s removal of Trotsky from Soviet photos to the false confessions at Moscow trials, memory and forgetting were often the lubricant that oiled the gigantic, menacing and often grotesque machine of totalitarian power.

Memory is built from many memories. There is individual and collective memory, the memory of winners and losers, natural and artificial memory, aural and visual memory, sensorial and intellectual memory, affective and cognitive memory, real and imagined memory, current and virtual memory, political and historical memory and poetic and photographic memory. These qualifiers can also be used for forgetting.

Going against classic philosophical tradition, which is hypermnesic, and against Plato’s theory of recollection, Friedrich Nietzsche gave forgetting a throne in the endangered kingdom of life. He did not deem amnesia an absolute gift, but made it a relatively precious asset on the unstable and restless scale that weighs memory and forgetting. He believed that forgetting was the foundation of ordinary life and a condition of happiness. It was for the mind what digestion was for the body. Its value had the brand of more and not of less and its positivity was an energy that led to action, a lightness that led to advancement, a joy that led to boldness and a power that led to building. ‘There is no happiness or serenity or hope or pride or enjoyment of the present moment without the ability to forget,’ he said.

The author of On the Genealogy of Morals felt that the prisoners that inhabited the prison of memory were served the heavy dried bread of resentment, rage and paralysis: remembering is ruminating and brooding. As an anti-historicist, Nietzsche regarded history not as principle of identity or as driver of unity but as a heavy weight placed on the bowed shoulders of all and sundry that prevented peoples from free self-determination. This cunning master of suspicion said that for people and peoples sense was not inherited; it was created.

Marcel Proust made time, memory and art the trinity of gods of a heretical literary theology. His book-polyptych-labyrinth-cathedral of seven books sought what is only given to us when we seek without finding to find without seeking. Life and death speak a language other than ours. Living is translating and translating is pursuing the word that is dispensed, exonerated and replaced. However, it is also achieving that which corresponds (co-responds), is equivalent (worth the same), swings (moves back and forth), adds and compensates. According to Walter Benjamin, a good translation contains nostalgia for the absent language.

By endowing involuntary memory with a clear, broad predominance over voluntary memory, this compulsive asthmatic nocturnal writer, who sought within himself the oxygen of another breath and the clock of another time, made the system of life coincide with the regime of art in voluntary memory.

After all is said and done, voluntary memory is perhaps the memory of chronos – linear, serial, successive, quantitative, human time – and involuntary memory is the memory of kairos – the right, opportune, ubiquitous, qualitative, divine time. This is why voluntary memory is vulgar, monitored and vulnerable, while involuntary memory is magical, magnetic and magnifying. Because, as Proust said, ‘The true paradises are the paradises that we have lost.’

Memory has been acquiring ever more techniques and technologies, buildings and institutions, processes and processing. Memory is in archives, inventories, registry offices, depositories, libraries, periodical libraries, sound libraries, video libraries, media libraries, cinema libraries, picture galleries, museums and monuments. It is on parchments, papers, fabrics, cellulose, films, vinyl and hard drives, and in clouds. Information has become memory and memory has become information. Memory without recollections (without data), which Foucault talked about when referring to Marguerite Duras, only exists for those who drop out of the world or cannot find a place for themselves in it.

For classic psychology, memory is the deep foundation of being, the founding foundation of identity, the powerful pillar of personality. It contains the sources of sense. In this light, without memory we do not know who we are. It is the awareness of us in us and of us in the world. This is the axis that gives unity to the rotations of plurality, the faces of diversity and the proliferation of the unknown.

But in his autobiographic essay Less than One, the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky, who was a dissident, prisoner and Nobel Laureate, wrote:

Share article