On the whole, with the notable exception of Morel, the son of a servant who is ashamed of his social origins but will end up as a respectable bourgeois, Proust’s characters are not grasping in the usual way of French nineteenth century novels, written against the background of the middle classes’ rise to power and the growth of capitalism. None of them tots up the price of a meal or thinks that the god of money is all-powerful. Proust’s purpose in describing the value of things is mostly to give a sense of reality, to expose social hierarchies and behaviour,2 to illustrate well-regulated attitudes or even to evoke snobbery, but hardly ever to define the characters’ natures. In Proust, unlike in the realist novels of Balzac, Maupassant and Zola, people rarely count their small change.

In À la Recherche du temps perdu, whether in terms of the social comedy or the tragedy of love, the battle for recognition takes precedence over greed – symbolic capital over financial capital. All readers of Proust are struck by the disconcerting and sometimes comic artificiality of society life as well as by its cruelty, always seeking out scapegoats in order to make the group stronger. Proust’s view seems to be that life is a matter of struggle and conflict for the man of the world driven by vanity and ambition, two passions seen as symbols of energy and as engines of change in the aftermath of the middle class revolutions of the preceding century. For the Verdurins, bourgeois archetypes of enormous wealth, their worth is not attached to money, although they are quite happy to display their financial means, but to art, which at the end of the nineteenth century was seen as a currency that helped you to stand out and make an impression. For example, they arrange for Wagner to be performed at a time when the composer was not yet appreciated in France. It is through society’s transactions that stocks of worth and social capital must be increased! This explains the importance placed on snobbery, that attitude which consists of appropriating the style and desires of others while belittling those whom it is pointless to envy. In fact the same inability to exist without constraints is found in relationships of love. Proustian egoism turns on the spiritual rather than the material: he does not seek to possess (as money allows) but to dominate (as the symbolic allows). The fact that money is only a secondary theme in Proust’s work should be viewed in the context of his focus on the interior lives of his characters, on the conflicts between their vanity and the cruel core of their libido, rather than on history and the economic development of society as it relates to the development of lifestyle and social relations.

Marcel Proust was thus supported by a private income – a piece of good fortune that he passed on to some of his characters, for example Swann, whose inheritance from his father was almost identical to Proust’s own inheritance – but he used the money to maintain relationships that were affective when they were not neurotic. It should be noted that while this was a cause for concern, because he always spent more than he earned, he never expressed any disapproval of money, as did many writers who were so clearly marked by French Catholic culture, reflected in many extracts from the Gospels – for example ‘you cannot serve both God and mammon’ (Matthew 6:24) – as well as in numerous literary stereotypes of the moneylender and the miser. So we have Gustave Flaubert, another man of independent means, showing how Emma Bovary’s debt will lead to her downfall, or Charles Péguy, who said that for the first time in history (this was in 1913) spirituality had been suppressed ‘by a single material power, the power of money’ for its own sake. Georg Simmel also demonstrated this, at around the same time, in The Philosophy of Money: he recognised the central role played by money in society because of its instrumental function. From being a means, as all money is, it can become an end in itself, finally replacing the urge to exchange with the urge to possess. There was another basis for the aversion towards money at the time, although it was totally foreign to Proust: the Parisian myth of the bohemian, which emerged at the time of the 1830 revolution and celebrated freedom, idleness and joie de vivre – a myth made famous by Balzac’s novella Un prince de la bohème (1844) and especially by Puccini’s opera La Bohème (1896).

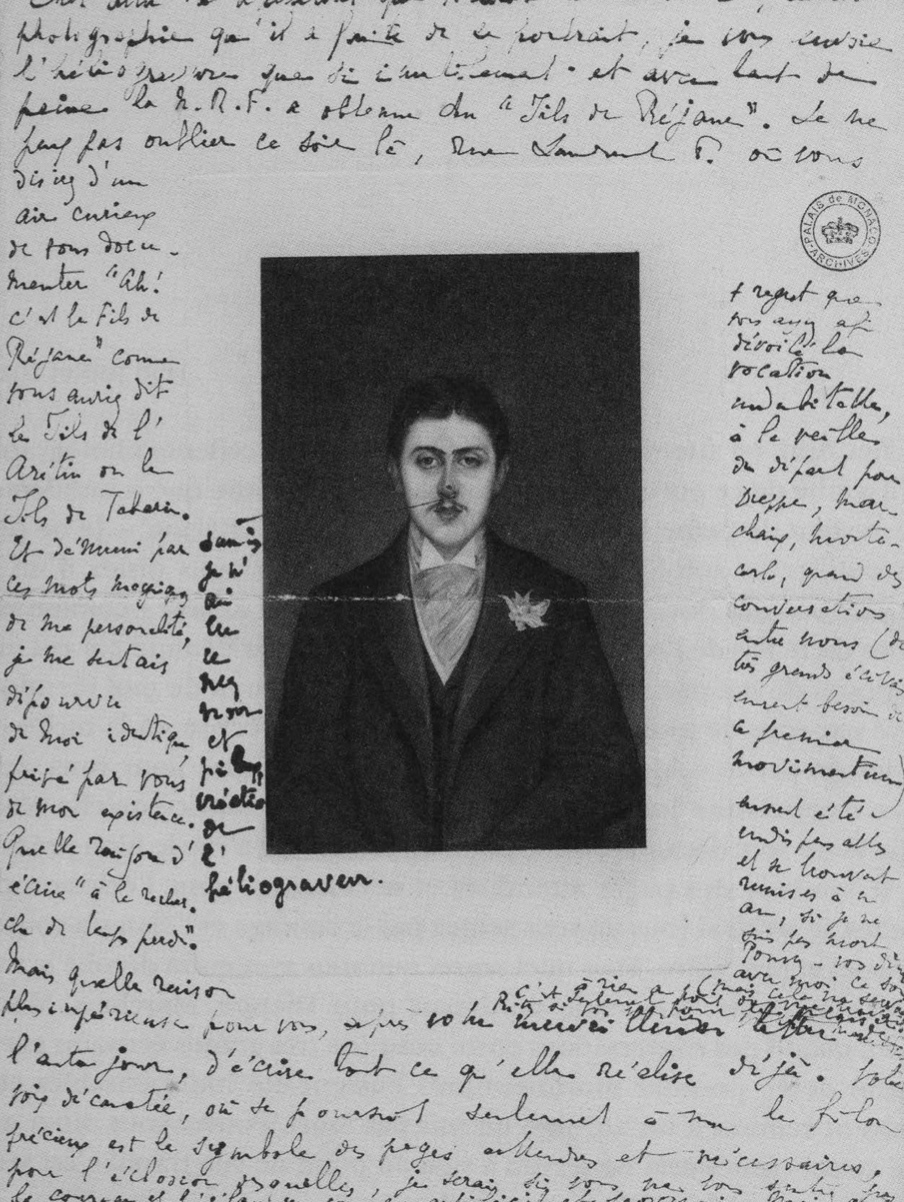

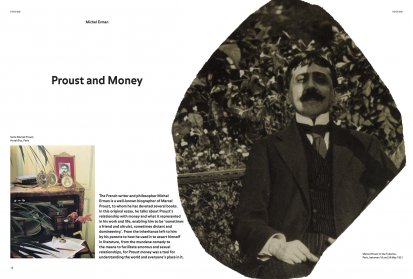

Born into a wealthy bourgeois family, whose interests included trade, banking, medicine and politics but for whom saving money was a virtue and increasing capital a duty, Marcel Proust inherited a small fortune after the death of his parents in 1905. Worth today around four and a half million euros, the inheritance was mostly banked with the Rothschilds and brought him, at least to start with, the equivalent of around 170,000 euros a year. But he spent freely, giving enormous tips as we have seen and placing large sums on the casino tables. Moreover, possessed by the demon of speculation, he was interested in the futures market, which fascinated him even more than baccarat. He had numerous financial advisors but to some extent set them up against each other, with the result that his stock market transactions were often high-risk: on the eve of war, he made some deals on the Paris stock exchange which turned out to be disastrous and then got into debt with Crédit Industriel, another bank where he held an account, buying securities on credit. He subsequently sold these securities (the equivalent of around 450,000 euros) in order to buy Agostinelli his aeroplane. After a series of unfortunate transactions to add to his ill-judged expenditure, Proust claimed to be ruined. This was something of an exaggeration for, while he had stripped his fortune of a good third of his assets and had less income coming in from his investments, he was yet not ruined, although his psychological balance was disturbed. It is worth noting, however, that after war was declared in August 1914, the financial markets closed. This, de facto, put an end to his speculations and probably saved him from financial disaster, according to the economist Gian Balsamo.3 However, there was a downside to this godsend: he would no longer receive foreign dividends.

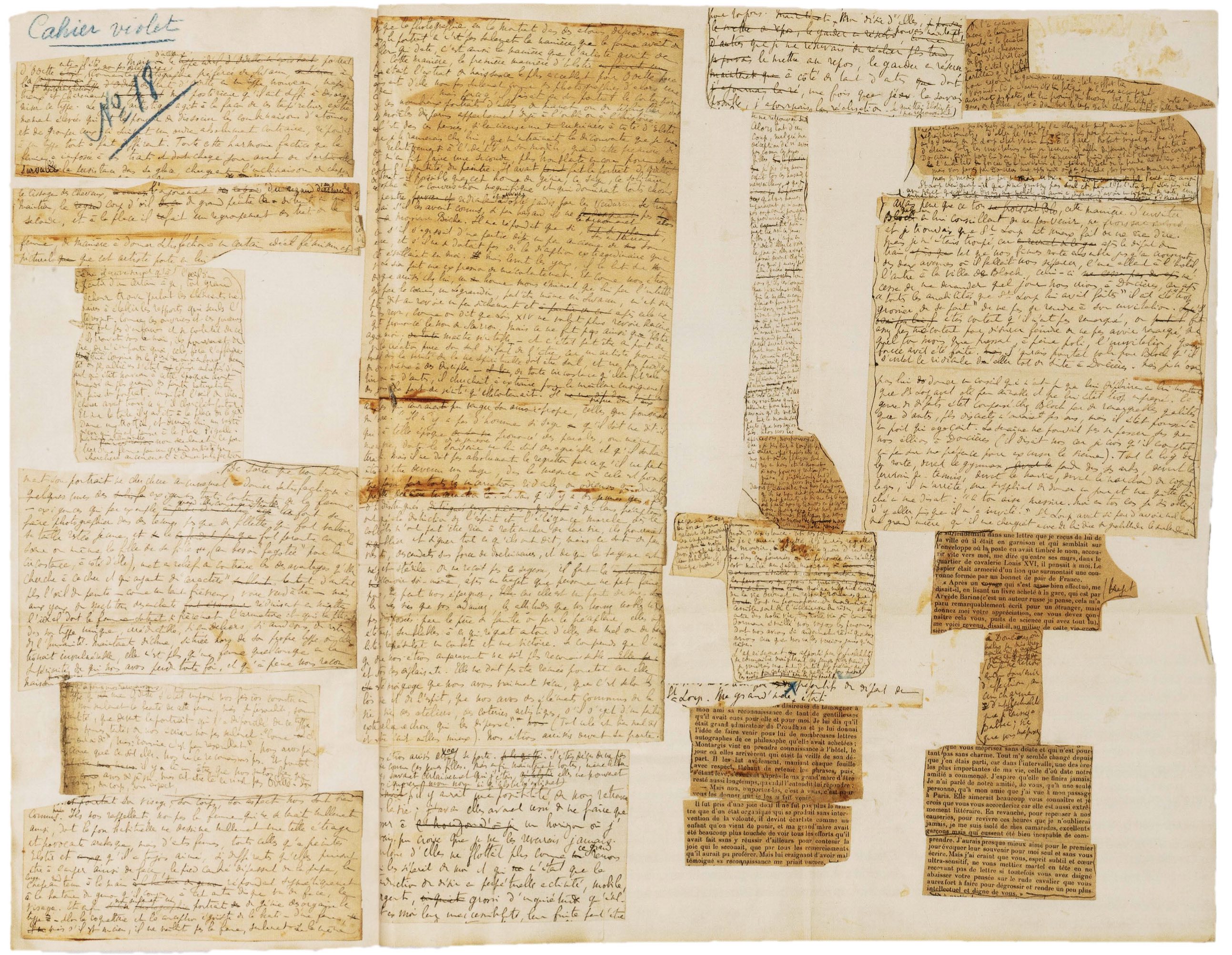

During the war, Proust entrusted his affairs in their entirety to his cousin Lionel Hauser, who would advise him and help him to manage his money. Hauser was an authorised agent for the Warburg bankers, having held the same position at Crédit Lyonnais. They had known each other since childhood and were fond of each other, despite the incomprehension that reflected the difference between them: in brief, while Proust was a spendthrift, Hauser was careful with money. It was through the skills of his cousin, in 1916, that Marcel’s financial liabilities were considerably reduced and his revenue doubled. After the armistice, Hauser made him invest prudently and as a result Proust gradually won back his lost capital. Additionally, after 1919, when he won the Prix Goncourt for À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs (In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower), his sales, which had until then been modest,4 grew significantly. From his new publisher, Gallimard, he had obtained royalties that would make any writer jealous (18% on the first three thousand copies sold, 21% thereafter). In 1921, the publisher started paying him in monthly instalments of three thousand euros. But the truth was, these royalties mattered little to him: what really concerned him was the reception of his work and its longevity.

From a psychological point of view, it is impossible not to connect his financial setbacks, which he set out in great detail in letters to his friends, with his many disappointments in love. It is as though they represented a reiteration of painful experiences, denoting a sort of pathetic complacency in defeat, even a kind of moral masochism. Money, like love, is experienced as an absence. Proust was in fact always afraid of lacking both – and he also liked to gamble with both. In terms of the conscious mind, it could be said that if he felt the need to gamble large sums at the casino as well as on the stock market, it must surely have been to give the appearance of participating in society, living as he did, for most of the time, shut up in his bedroom – with his last few years spent writing. Ultimately money provided him with the substance for a sort of Pascalian diversion. From a rational perspective, money gave Marcel Proust the freedom to devote his entire life between 1908 and 1922 – the year of his death – to À la recherche du temps perdu, this great novel encompassing existence and the emotions. He put all his energies into it, to the extent that when a journalist asked him what manual job he would choose if forced to do so to survive, he replied: ‘The job I do now: writing.’ The novelist François Mauriac said of him: ‘He was a man of letters who loved letters enough to die for them.’ It is safe to say that the material conditions of his existence saved him from the fate of Alexandre Dumas and Balzac, who lacked money and were forced to write for a living. Proust celebrated literature as an antidote to suffering and death, a way of countering worldly vanity and the destructive power of oblivion with the permanence of being.

*Translated by Emma Mandley / KennisTranslations

Share article