The portfolio we present here was prepared for Electra by one of the most renowned and most innovative artists of our time. He is also one of the most sophisticatedly learned and most effectively communicative.

In this work, William Kentridge couples semiology with iconology and finds the sacred meaning and profane use of words. By placing these two modes face to face, he creates through their coming together an indeterminacy and interrogation. These works are like visible sparks emitted by the incessant breath of an invisible fire. They are thus both familiar and strange to us at the same time.

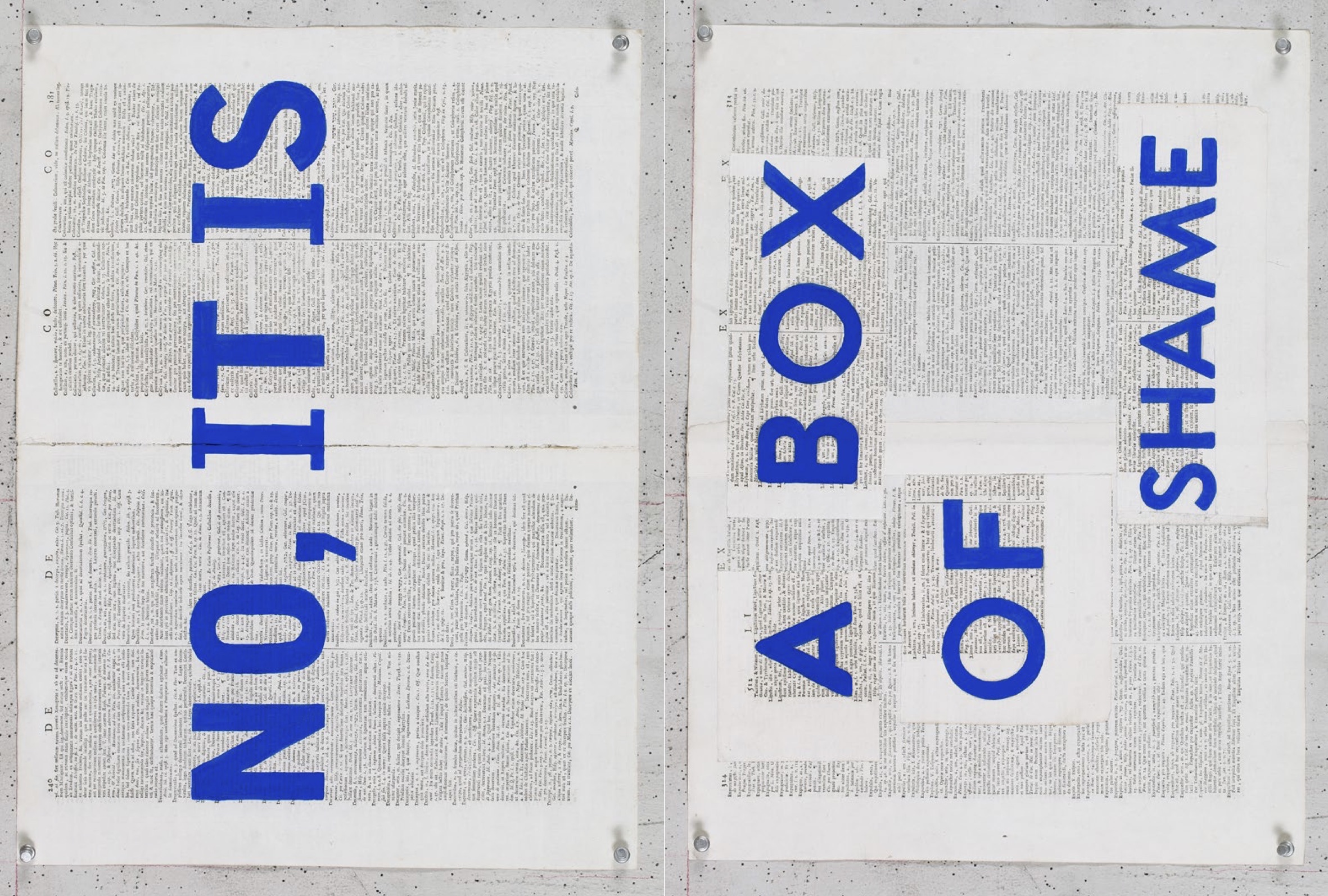

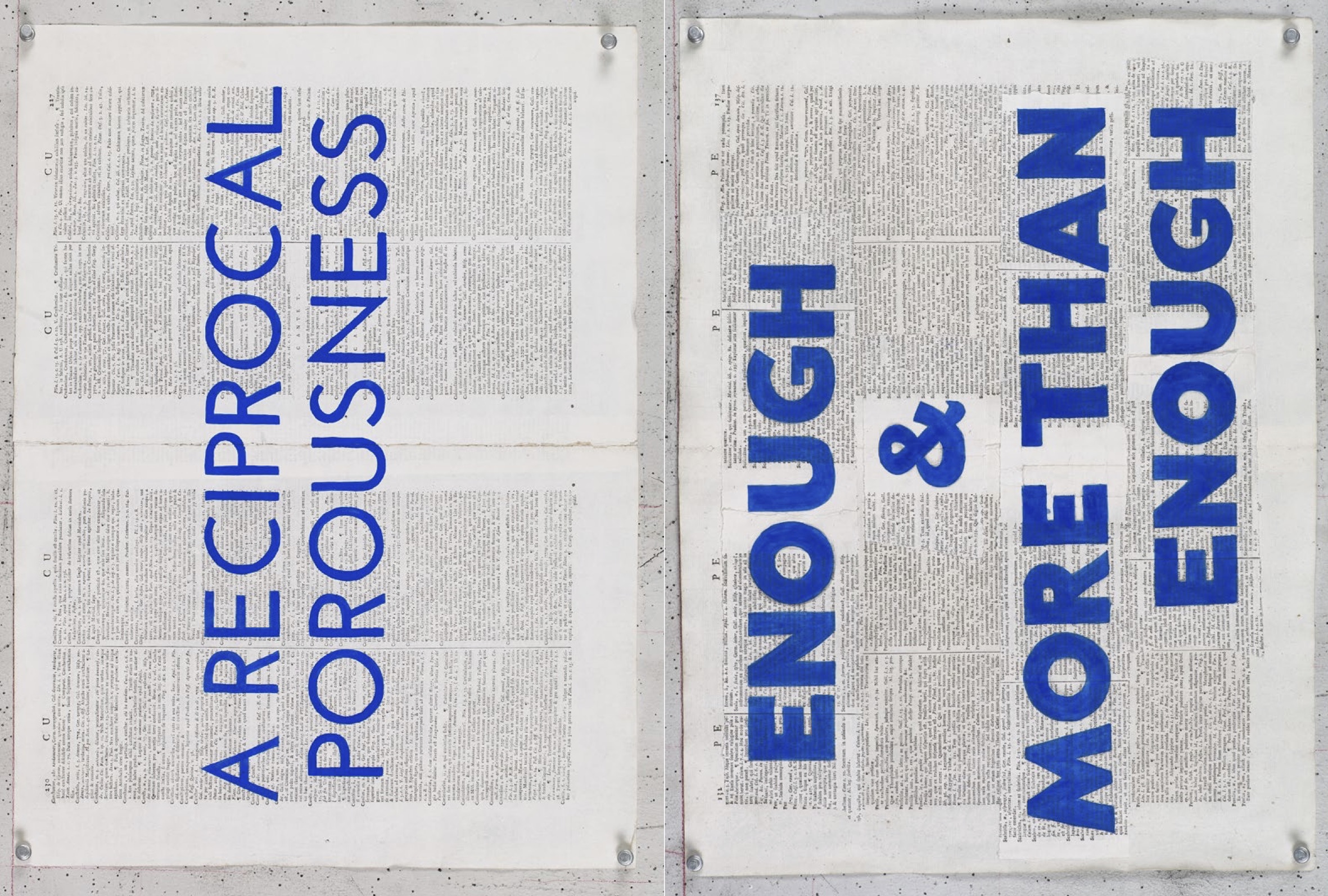

The artist’s starting point can be found in the red notes which accompany the illuminated or printed liturgical text in religious books from which we learn to pray. These notes are called rubrics. By exchanging red for blue, he also exchanged the visual sign (and history, as Pastoreau shows) of one colour for that of the other, creating an imbalance between it and its memory and chromatic etymology, and making it a symptom.

The origin of the blue in these “blue rubrics” lies in a present given to the artist: gouaches composed of lapis lazuli pigments from Afghanistan. Aware of the symbolic transgression he was making, Kentridge accompanied it with a translation, giving the words – or sets of words – he drew-wrote the function of footnotes of a thought. In this way he located them at the extremities, or the margins, or the limits, of this thought. They are like harmonious series.

Kentridge explained that these words-expressions-phrases hover over or surround the centre of meaning: they are fragments long kept in a drawer and represent unresolved enigmas. He sees these words and phrases as a stimulus to the activity of thinking and the sign that we have to give sense to the world from contradictory fragments, imperfect messages and incomplete evidence. They are the words of a vision and a vision of the words.

There are visual physics and linguistic metaphysics here. A philology, a love of words. A verbiage and iconoclasm. These words live between two time periods: the prologue (that which is before the word) and the epilogue (that which is after the word). Around them circles this question: do they echo the performative sounds of Genesis or the lethal images of the Kentridge explained that these words-expressions-phrases hover over or surround the centre of meaning: they are fragments long kept in a drawer and represent unresolved enigmas. He sees these words and phrases as a stimulus to the activity of thinking and the sign that we have to give sense to the world from contradictory fragments, imperfect messages and incomplete evidence. They are the words of a vision and a vision of the words.

There are visual physics and linguistic metaphysics here. A philology, a love of words. A verbiage and iconoclasm. These words live between two time periods: the prologue (that which is before the word) and the epilogue (that which is after the word). Around them circles this question: do they echo the performative sounds of Genesis or the lethal images of the Apocalypse?

The words-images we see here inhabit, as their author says, a place between reading and looking. They are parts of a whole that no longer exists – or does not yet exist. Instead of clarifying things, they become unsolvable puzzles, unanswerable riddles, unheard secrets, unencoded ciphers. They glimpse us when we glimpse them. They create echoes, associations, mnemonics, queries, references and nooks. They are abbreviations of a big idea, titles of a long piece of writing, contents of an infinite book.

This polysemic indeterminacy and openness in meaning are a property shared by sacred and poetic writing. This visual Morse code receives and innovates a manifold genealogy that comes from the Kabbalah, from Plato’s Cratylus, from Scholasticism’s logomachy, from baroque cryptography and cryptograms, from chicken-foot tables, from Mallarmé, The Book, from the verbal and visual games of the Modernists, Futurists, Lettrists, Dadaists and Surrealists, and from visual poetry.

Through this work with letters, words and images, the artist ponders his thought, revisits his oeuvre, questions his life. And, at the end, perhaps he can finally exclaim like Fernando Pessoa, who grew up and studied in South Africa, “Don’t give me conclusions! / The only conclusion is to die.”

William Kentridge was born in Johannesburg in 1955, the son of parents who defended various victims of apartheid in court, his father having been Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu’s lawyer. He studied political science, fine arts and, later, drama. The experience of violence, exclusion, humiliation, rage, blindness and fear of the regime will stay with him forever.

His multiform oeuvre, realised in various fields, disciplines, media, physical media and techniques, moves between the performing arts (opera, theatre, conferences) and the visual arts (in their various disciplines), ranging also from art to literature and literature to science. In his work, everything that arises converges.

Anything in it that is self-portraiture and autobiography extends the world and is extended in the world. A lucid and courageous political, social and cultural awareness of the world runs through it. For Kentridge, the artistic act is an act of creative intervention and creation that thereby amplifies, erects, pluralises, reinforces, symbolises and transfigures the singular testimony.

The winner of various prizes (for example, the Princess of Asturias Award for the Arts in 2017), he has held exhibitions and performances at major museums (the Louvre, Jeu de Paume, Whitechapel Gallery, Reina Sofía and Tate Modern) and in many cities (London, Paris, Berlin, New York, Sydney, Kyoto, Madrid and Johannesburg). He has participated in the most renowned art events (Venice Biennale, documenta, Bienal de São Paulo) and has worked for prestigious theatres and festivals (La Scala in Milan, the New York Metropolitan Opera, the Opéra de Lyon and the Salzburg Festival).

The author of this portfolio is an artist who is simultaneously universal and rooted, intimate and social, personal and representative, individual and collective, contemporary and historical. His alphabet specifies what is closest and most distant. Time is thus today one of the focuses of Kentridge’s work.

In his oeuvre, drawing, which includes cartoons, is the engine that constructs movement and rest, revelation and concealment, adventure and the audacity of it. From writing to dance, from stage sets to drawings, it is with drawing that he thinks, feels, imagines, experiments, remembers and forgets. And proposes, prophesies, forgives, accuses, advances, listens and sees!

In his drawings, paintings, engravings, collages, sculptures, photographs, videos, films, performances, stagings, set designs, acting roles and conferences, everything is interwoven in a knot of particular and general memory that apprehends, tying and untying itself in images, signs, movements, impulses and emotions.

This work of memory (one can speak here of the “work of memory” as Freud spoke of the “work of mourning”) unleashes revelatory probes from an acute, active and agile curiosity about everything. Kentridge has also taken possession of some of the great literary canons of our culture, bringing his voice – and our own – to them as if wishing to answer Italo Calvino’s question, “Why read the classics?”

In him, “I” becomes “you” and “I” and “you” become “us”. In this path of communication and coming together in which the particular is made general, the physical mental and the natural cultural, without ceasing to be what they were, art becomes the world: the world happens as it does happen (Wittgenstein). And with his letters drawn in words, sometimes on pages of books, maps and newspapers, he writes the world.

Like artists who are unashamedly so, Kentridge refuses all simplifications and assumes all complexities. That is why he says that he is interested above all by uncertainty, by ambiguity, by the absurd, by paradox and by contradiction. That is why he affirms that, when he creates art, he does not know what he is creating until the moment he creates what he creates, and that he does not completely control the process and result, which is the sign of a possible adjustment.

Recognising the inheritance of the Dadaists, Kentridge says that we owe them the ability to work with sounds, silences, texts, poetry, images, happenstance and disarray. And he recognises that he has a love-hate relationship with Duchamp and others like Bruce Nauman because they worked with the haughty and worn confidence of those who are at the centre of the world.

But he recognises that it is now possible to work at the periphery (a place, he stresses, which has philosophical, geographical and economic interest) and be seen in the centre. And notes that Europe’s errors can be better observed from the periphery. “In peripheries such as South Africa, one always knew that life was risk.”

And Kentridge also always knew that art is the risk of this risk.

José Manuel dos Santos

Share article