Talking about the media in these times of dizzying communications and this world of noisy networks means talking about dissemination, depreciation, multiplication and proliferation. And it means talking about that chaos, whose laws are those of our anxious bewilderment in the face of it.

It means talking of media power, chaotic, irresponsible panoptic power (also in the legal and ethical sense), though it is abundant, pulverised, proliferated, polymerised, empowered and caught in meshes of micro powers, some of which are domesticated and others untamed, working in their micro-spheres (Michel Foucault).

The moving world of the media is similar to that sphere that Pascal gave to the universe, as being its most powerful and possible image, and that Jorge Luis Borges loved so much: an infinite sphere, the centre of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere.

It is as if the media are a magnet for the misunderstandings, illusions, deceptions, hoaxes and perversions of our time. This is why the classic, heroic discourse that still speaks of information in our democracies in an epic tone and of freedom of the press in a lyrical manner sound so strangely hollow and inappropriate, so useless and anachronistic.

With an inescapable connection, we therefore feel that the generous, headstrong, tired and infallibly applauded discourse of old, pompous, enlightened humanism about freedom and democracy is vain, ineffective and slightly deluded. These two discourses are the head and tail of the coin with which we buy the good conscience that lies to us and makes us happy.

There is no point in not knowing or pretending not to know what is happening. As Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen wrote in a poem that was written during the dictatorship and became a slogan of resistance, rejection and protest, “We see, hear and read / We cannot turn a blind eye.”

What is happening in the media today (including social networks) is of an unacceptable brutality and, quite often, vulgarity. It is of an unsustainable lightness and, quite often, levity.

Those were the days when television was the conduit for major social, cultural and political disputes on the present and the future. It was pilloried by radical critics and bitter prophets. In the United States in the 1970s, The Last Poets declaimed, “When the revolution comes some of us will probably catch it on TV”, while Gil Scott Heron sang, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. In the 1990s, full of live broadcasts of wars, invasions, riots and massacres, the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy called it Television, the Drug of the Nation.

Every day, we see the publication of works that rub salt in the wounds and drip with the blood flowing from them. Every day, we see chilling diagnoses and ineffective treatments. And the crisis sails on like an invincible armada on the deadly, stormy ocean of the days that follow each other in waves.

These works talk of heteronomy, a change of paradigm, concentration, technologisation, trivialisation, commoditisation, industrialisation, massification, instrumentalisation, manipulation, de-credibilisation, mediarchy, populism, conformity, sensationalism, infantilisation, dictatorship of ratings, media doxa, alienation of audiences, loss of influence, unsustainability, unfair competition, media waves, synchronisation of emotions, globalisation of affects, pseudo-events, militant depoliticisation, promiscuity with justice, submission to neoliberal ideology, advertising agencies, the tyranny of communication, fake news, fake profiles, fast thinkers, trolls and tweeters. And also of cyber-journalists, hypermedia, alter-media and solution journalism.

It has been said that there now seem to be only two figures in the media. They are the intern, that new proletarian without Marx, who is exploited and willing to be so, and the manager, that new bourgeois without Kant, who is the exploiter, and unwilling to be anything else. Between the two, there is a no-man’s land and every-man’s land. This is the place for the rest, those who survive, those who suffer, those who resist, those who crawl, and those who break away. This has been called the Taylorisation of the journalist’s profession.

The history of the press and its freedom has its heroes and martyrs, and this moral memory may be inspiring. And it has scoundrels and cowards, and this immoral memory may be a deterrent.

Newspapers and journalists have obviously always been the target of many accurate and off-the-mark, many fair and unfair attacks. The worst attacks have often been against each other, and much more noisy than those of others who attacked them.

We can take a journey through the literature of the last two centuries on board a hot-air balloon moved by the wind that blows and whistles from attacks on journalism and journalists.

From the scorn of Balzac to Camilo’s diatribes, the infamy of Palma Cavalão de Eça to the merciless portraits of Raul Brandão, Flaubert’s clichés to Evelyn Waugh’s satire, Proust’s ironies to Karl Kraus’s fabulous aphorisms, there is a collection of accusations, sarcasms and swearwords, some of them brilliant, that have detected and called out journalism’s stupidity, ignorance, venality, vileness, promiscuity, manipulation and calumny. We know that part was often taken for the whole. But we also know that there were moments when this part almost covered the whole…

Today, however, we are – or should be – acutely aware that the crisis in journalism is of a different nature, dimension and complexity, and of a different severity. Carried by the force of things and by our own weakness in relation to them, we have gone from concession to concession, abdication to abdication, and have also conceded our conscience and given up our right to have one.

Today, everything is confused: information, opinion, entertainment, presentation, journalism, comment, humour, fiction, social diaries, legal discourse, retail, marketing, advertising, charity and propaganda.

Every day the extreme and disturbing scenario in Sidney Lumet’s film Network (1976) seems perfectly plausible.

TV newsreaders have dreams of a glorious career. They want to be stars who are as famous, popular and well-paid as the hosts in the next hour’s programme, who hand over prizes in a bodybuilding competition or a reality show. Or they want to be like the comedians who tell jokes and do pirouettes while they tell them or like the soap opera actors or actresses whose only visible talent is their exuberant anatomical attributes.

Without this easy, fallacious fame, the newsreaders know that their sub-existence or even non-existence diminishes, compromises and degrades them and, at the limit, might banish them into that exile of having to leave the screen or the station. To avoid this and ensure “public interest”, they run to the gossip magazines to tell their stories since childhood, their sex life since adolescence and their illnesses since diagnosis. They show off their bodies, homes, gardens, partners, children, parents, parents-in-law and friends. They talk about their dating, marriage, cheating, divorce and reconciliation.

We see, hear and read and cannot ignore that journalism today often seems to exist to prove the accuracy of the remarks and the dark, even sinister prophecies by Guy Debord in The Society of the Spectacle and other works. One of them says, “The spectacle is not a set of images; it is a social relationship between people mediatised by images.” Another says, “Audiences do not find what they want; they want what they find,” or “In a world that is indeed upside down, the true is a moment of the false.” Or finally, “Culture that has totally become a commodity will also become the star commodity of the society of the spectacle”.

Journalism lives between the current threat and the many to come. And to thwart the threats made against themselves, the media use the threats that they make against others. This back-and-forth between aggressive arrogance and submissive subservience, which we can call resigned, resented and resistant self-sufficiency, portrays this dangerous dance as a clandestine casino game. And as happens in these lawless places, you cannot win, even if you win! You are playing with fire with hands already burned by it.

We know (and even those who do not want to know are aware) that the situation and its enormity can be described as follows. All dependencies add up; all precariousness builds up; all instabilities are joined; all pressures are brought together; all horizons are closed; all risks grow.

The risk tree has many branches and is evergreen. Its copious treetop therefore covers everything with a silent, sombre shadow. The branches extend and represent economic risk, technological risk, labour risk, cultural risk, social risk, ethical risk, deontological risk, political risk and civilisational risk. Being a journalist today means, in many cases and places, living in a permanent state of alert (or even a state of siege).

It is obvious that the media are a magnet for the misunderstandings, illusions, deceptions, hoaxes and perversions of our time, of which they are also the fingerprint that identifies and discloses, the voice that screams or remains silent, the eye that opens or closes and the colour that grows brighter or duller.

The media are restless, starving animals in the cage of our time, which is not ours at all. From this muddy, claustrophobic time, they feel the tremor and are overrun by speed, haste, pulses, changes, obsessions, clichés, traps and earthquakes. They suffer the earthquake and are the seismograph, even if this is involuntary and they are unaware of what they are.

We cannot try to understand this time and this world without looking at the media’s rises and falls, concessions and resistances. We cannot understand them without going down the Via Sacra of this story of pain, crucifixions and occasional resurrections. Or without staring down the temptations of the devil, Herod’s condemnations, Pilate’s washing of hands, Veronica’s veil, Peter’s denials and Judas’s betrayals.

When we think about the media and journalism, we think about distancing ourselves from the temptation of simplification, sensationalism and superficiality (to which a large part of that pair so often succumbs).

By addressing the media and journalism, Electra is continuing its programme of thinking about some of the issues, myths and images that figure in and configure our time.

This is a matter that triggers emotions and commotions, divergences and disputes, vociferation and vengeance, and defences and self-defences. It offends convictions and conveniences, and stirs up intrigues and interests. Here we want to regard it with agile serenity and with a distance that wants to draw near to the sound of the engine that sets the sphere in motion and also stops it.

We are aware that we are a magazine and that addressing a subject that is closely associated with us and vehemently challenges us is always a double-edged sword. Or it is the launch of a missile that may have a boomerang effect on us, the aborigines of the future.

Nonetheless, we know that this risk is useful, vital and relative. Because running this relative risk over all the absolute risks in this disturbed and disturbing world of the media is not even a test of courage; it is just a need for lucidity.

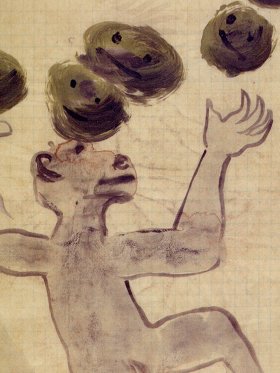

In this edition we show you the portfolio of the well-known artist William Kentridge. We also talk about two exhibitions in Paris, one by Rui Chafes and Alberto Giacometti and the other by Paula Rego. They are different artists but they are the same in that lack of the cowardice that accommodates and submits to everything.

Each of them has looked and seen with eyes that did not close to the light or the darkness. Their works are crafted around a space of silence pierced by the voice of a will that does not waver.

Talking about them is to assert that, in this world of lightning without light and thunder without the gloom, there is still a place for what we need, even if we are unaware of it.

*Translated by Wendy Graça

Share article