introduction

In 1905, a young German Jew called Albert Einstein, then just a simple clerk in the Berne patents and intellectual property bureau, published five articles that shook the foundations of physics, making their author an icon of the twentieth century, the archetypal genius and model for the role of a scientist. The early studies and education (1895-1901) of this young man are the key to understanding the annus mirabilis of 1905 – and the years that followed. This period, less well known than others in his extraordinary life, is described and interpreted here by the science historian Christian Bracco, author of the recent book Quand Albert devient Einstein.

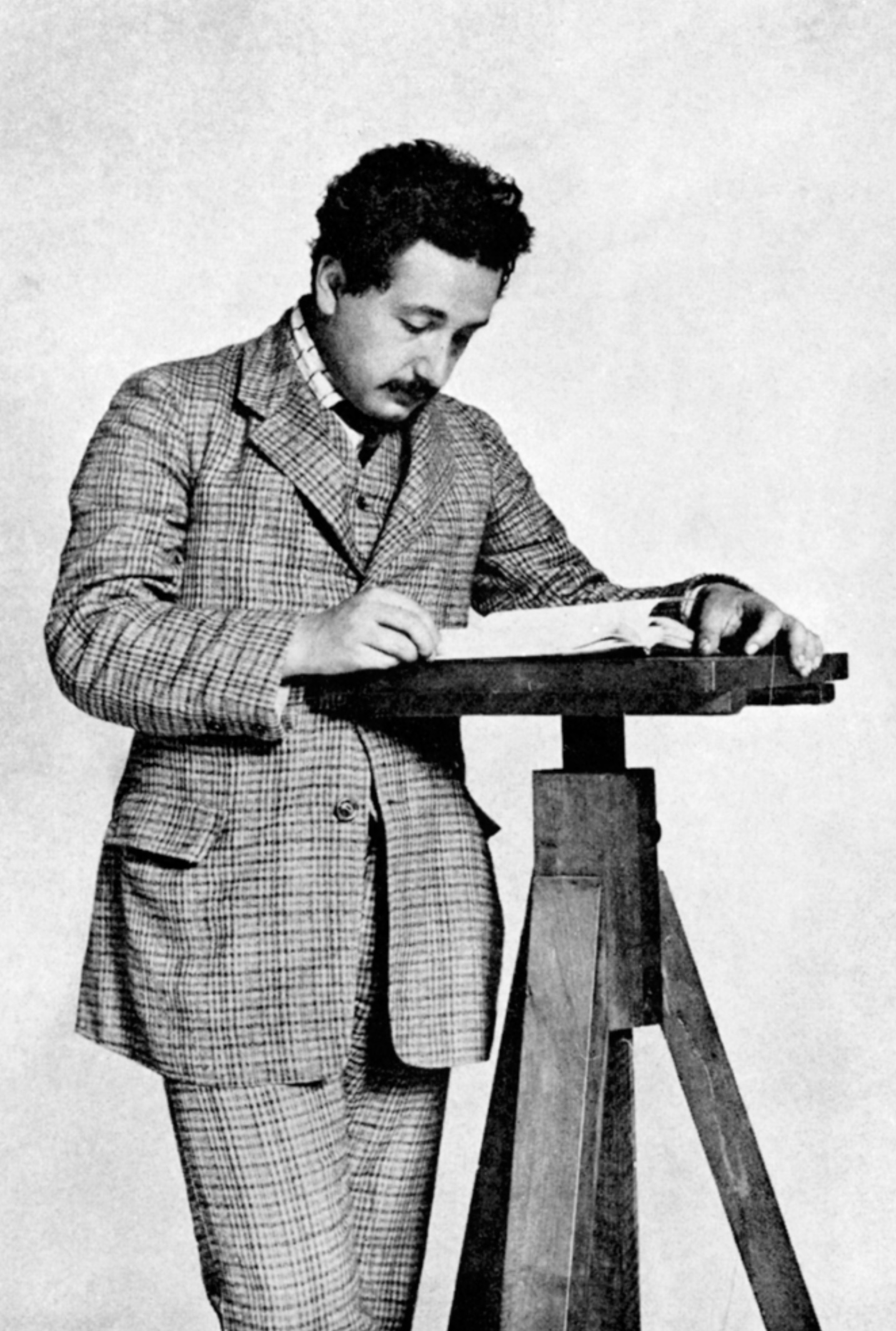

Albert Einstein, 1905

© Fotografia: Universal History Archive / Getty Images

The years 1895 to 1901 played a central role in the scientific education of Albert Einstein (1879-1955), if only because they included the years between 1896 and 1900, when he was studying at the Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich (now ETH Zurich). However, it was earlier, in 1895, that the young Einstein decided to enter this prestigious college, even though he was not old enough and lacked the qualifications. As for 1901, the young physicist was at that time working on a dissertation, although he had not obtained an assistant teaching post. These transitional years provide an opportunity for shedding light on his scientific environment and his working method.

We must go to northern Italy, Lombardy to be precise, to explore the traces of these times. This part of the young Einstein’s personal history has so far only been examined from the perspective of the business or social aspect of the Einstein family’s life in Italy. But we can site these formative years in their context and so better understand Albert Einstein’s first scientific orientations through a closer reading of the correspondence between Einstein and his sweetheart Mileva Maric (Collected Papers, 1987) – whom he would marry in 1903 – as well as through an analysis of his scientific connections in Italy. The result of this research was published recently in Quand Albert devient Einstein (Bracco, 2017). This article revisits a few of the new or lesser known points contained in this work.

the move to italy and his links with the electrotechnical milieu

Following the International Exhibition of Electricity in Paris in 1881 – the first exhibition devoted exclusively to developments in electricity – the Einstein brothers, Hermann (Albert’s father, 1847-1902) and Jakob (Albert’s uncle, 1850-1912), focused on this sector in their newly established business in Munich. The following year, in 1882, they played an active role in the international exhibition that was held in their own city and, later, in 1891, in another exhibition in Frankfurt. In 1894, following a failure to conquer Munich’s electricity market in 1893, the Einstein family, who already had a connection with northern Italy, went into partnership with an engineer from Turin, Lorenzo Garrone, and with Angelo Cerri, geodetics assistant at the university of Pavia, to set up a new electrotechnical business. This company, with eighty staff, was based in Pavia, south east of Milan, and had offices in Milan and Turin. The Einsteins went on to install electricity in a number of Italian towns and businesses.

Jakob Einstein was an engineer trained at the Stuttgart Polytechnic. He filed several patents in the field of electrics. It was with him that the young Einstein made his first ventures not only in the field of mathematics but also electrical engineering, in particular through the engineering journals that filled his uncle’s office in Pavia, where he occasionally worked. He was then around fifteen years old and had not been to school since December 1894, when he left the Luitpold Gymnasium in Munich to join his family in Italy. His uncle’s connections in the electrotechnical milieu allowed the young Einstein to contemplate continuing his studies at ETH Zurich. A letter dated 12 August 1895 has recently been discovered by Professor Andrea Silvestri of the Polytechnic University of Milan: here we find the young man, then sixteen years old, writing very respectfully to Galileo Ferraris, professor at Turin’s Industrial Museum, who at that time was considered to be the “father of electrical engineering”. Einstein had already been introduced to Ferraris and was now asking him to send a “small private reference” to his colleague Heinrich-Friedrich Weber, professor of electrical engineering at ETH Zurich, whose classes Einstein wished to follow.

Louis-Oscar Roty, Medalha para a Exposição Internacional de Electricidade, Paris, 1881

carlo marangoni

The years in Pavia were also marked by the young Einstein’s encounter with Ernestina Marangoni, who was three years older than him, in the summer of 1895. The Marangoni family lived in a sumptuous villa at Casteggio, near Pavia. Genealogical research carried out at the diocesan archives has enabled me to establish that Ernestina’s uncle was the physicist Carlo Marangoni. Although Marangoni lived in Florence, where he was professor at the Technical Institute, he returned to Casteggio once a year for the festival of the grape harvest, which Albert Einstein also attended between 1895 and 1900, staying with the Marangoni family. These were times that he counted among his happiest memories. It is easy to imagine the informal conversations between the aspiring young physicist and the professor, who was also interested in the science of education. What subjects might they have discussed at that time?

Carlo Marangoni graduated from the University of Pavia in 1864, with a dissertation supervised by the physicist Giovanni Cantoni, for whom he also acted as assistant between 1865 and 1866. Carlo’s dissertation focused on capillary phenomena. In physics, he gave his name to the Gibbs-Marangoni effect, which describes the transfer of matter when two liquids with different superficial tensions come into contact with each other. He would go on to publish around eighty articles over the course of his career as well as several books. Einstein’s links with Carlo gave a new impetus to his interest in capillarity, the subject of his first article in the journal Annalen der Physik, in March 1901. Formerly, historians linked this interest with Minkowski’s lectures at ETH Zurich. It is worth noting that in his 1907 article on capillarity for Sommerfeld’s Encyclopedia, Minkowski cites Marangoni on three occasions.

As for Giovanni Cantoni, he is known in particular for his 1867 kinetic interpretation of Brownian motion in particles of pollen suspended in liquid. Marangoni must have been very familiar with this research: not only was he Cantoni’s assistant in the months preceding the publication of his work but in 1867 he was assistant to Matteucci, one of the principal editors of the journal Il Nuovo Cimento, in which Cantoni’s article was published. It should be remembered that the precise quantitative interpretation of Brownian motion was the subject of one of Einstein’s celebrated articles in 1905.

michele besso and his family

It is well-known that, at the end of his article On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies (June 1905), Einstein thanks his friend Michele Besso (1873-1955) “who steadfastly stood by me”. He would tell one of his biographers, Carl Seelig, “I could not have found a better sounding-board in the whole of Europe.” When I visited the Marco Besso Foundation in Rome in summer 2014, I found a letter from Michele Besso to his aunt, dated 13 June 1913. This letter contains a subtle allusion to his relationship with Albert Einstein, at the time when he (Einstein) was developing with Marcel Grossmann, and then testing with Michele himself, the first version of his theory of general relativity. Michele concludes, “I [...] will return there [to Zürich] to watch my friend Einstein struggle with the great Unknown: the work and torment of a giant, of which I am the witness – a pygmy witness – but a pygmy witness endowed with clairvoyance.”

To better understand his role at Einstein’s side, we must return to Michele’s family and the context of their meeting.

Giuseppe Besso, Michele’s father, was one of the directors of Assicurazioni Generali, a large insurance company founded in Trieste. He married Erminia Cantoni in 1872 in Zurich. On the Besso side, Michele had three uncles: Beniamino, director of the Sardinian railways and author of works on physics and popular science; Marco, who would become, inter alia, executive director of Assicurazioni Generali; and Davide, who studied at Pavia and became professor of mathematics at the University of Modena. On the Cantoni side, Michele had several uncles and aunts, including Vittorio, a graduate of ETH Zurich and the Milan Polytechnic, who set up the first electrical transformers (studied by Ferraris) at Tivoli in 1886, and Giuseppe Jung, an uncle by marriage, professor of graphic statics at the Milan Polytechnic and a member of the Lombard Institute Academy of Science and Letters. It was to him that Albert Einstein turned in April 1901 when he was seeking an assistant teaching post in Italy so that he could continue with his dissertation. The records of the mathematics libraries of the Polytechnic and the University of Milan (the Jung endowment) show that Einstein sent him offprints of his first twelve articles, up to 1906.

Michele Besso graduated from ETH Zurich in March 1895, just when Albert Einstein was trying to enrol, as he later put it, “without it being clear as to how I should go about it”. It seems likely that the friendship between the sixteen-year-old adolescent and Michele, six years older, was cemented around the issue of the young man’s admission to ETH Zurich. Factual confirmation exists in a letter from Michele to Albert Einstein, written on 10 October 1945, in which he implicitly refers to the year 1895, subtly commemorating the anniversary of their meeting: “Isn’t that once again our starting point more than fifty years ago, between Newton and Huygens?” Their first meeting thus took place, on scientific evidence, before October 1895, when Einstein was dealing with the question of enrolling at ETH Zurich. It should be noted that it is necessary to go back to the original letters in German to find the exact reference to “more than”, which does not appear in the French translation of the Einstein-Besso correspondence (Speziali, 1979). Our research shows that this meeting was in fact made possible as early as 1895 as a result of the close relations between the business and financial milieus in which the Einstein and Besso families moved.

The friendship between Michele Besso and Albert Einstein became firmer as time went by and the links between their families became stronger: in 1897, Michele married Anna Winteler, who had been introduced to him by Albert Einstein. She was one of the daughters of Jost Winteler, head of the Aarau school that the young Einstein had attended during his final year of secondary education from 1895 to 1896. Meanwhile Maja, Albert’s younger sister, married Paul Winteler, one of Anna’s brothers. From 1900 to 1901, Michele worked in Milan for the Society for the Development of Electrical Enterprises in Italy and met Einstein on a daily basis during the latter’s holidays. In September 1900, Einstein wrote to Mileva, “I am spending many evenings at Michele’s”, and, in March 1901, “Yesterday evening I talked shop with him with great interest for almost four hours. We talked about the fundamental separation of luminiferous ether and matter, the definition of absolute rest, molecular forces, surface phenomena, and dissociation.” This gives us an invaluable glimpse into the variety of subjects they discussed together.

the library of the lombard institute

Until now there have been no precise details of any scientific work carried out by Albert Einstein in Milan, where his parents settled again in autumn 1896 after the sale of the business in Pavia. Now, during his biannual holidays in March/April and September/October, Albert Einstein joined his family there and continued with work he had begun in Zurich, firstly for his Diplomarbeit and then for his first dissertation. Two consecutive letters, dating from the beginning of April 1901, provide confirmation that Einstein was at that time working in a specific library in Milan where he was undertaking bibliographical research, as would be normal for a post-graduate student.

"Milan was a paradise of freedom and beauty. For the first time in his life, Einstein studied the plastic and graphic arts: The Last Supper of Leonardo da Vinci at Santa Maria delle Grazie, the collections at Brera – a world of classical beauty!"

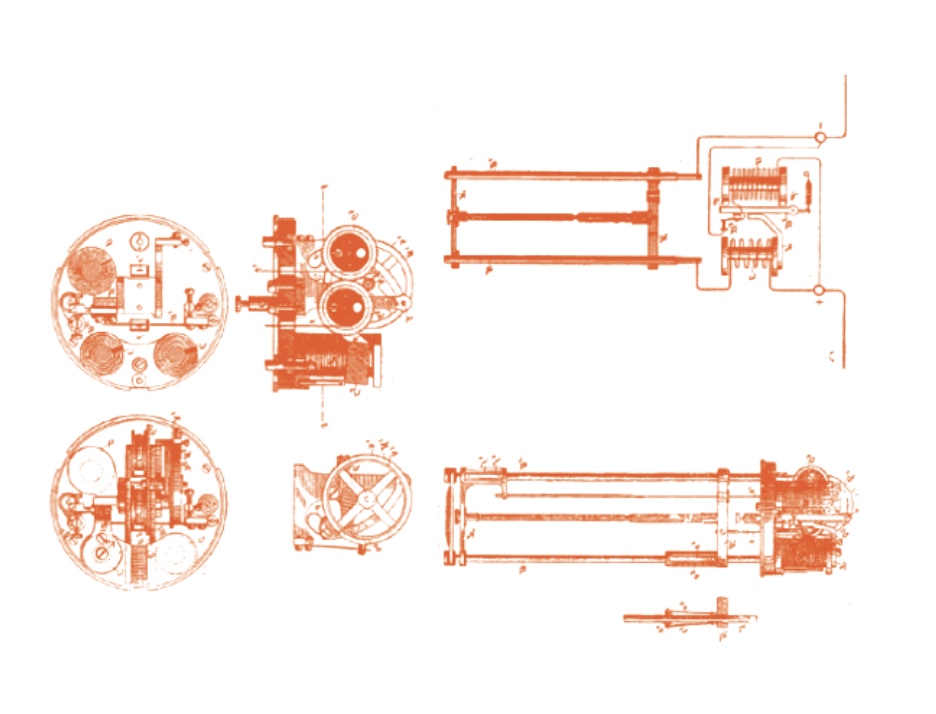

Sistema de lâmpadas diferenciais Jakob Einstein, in Gustave Richard, «Les lampes à arc»,

La lumière électrique, 49 (1893), pp. 313–319

On 4 April 1901, Einstein wrote to Mileva, who had remained in Zurich: “On the other hand I have in my hands a study by Paul Drude on the electron theory … He also assumes that it is mainly the negative electrical nuclei without ponderable mass which determine the thermal and electrical phenomena in metal, exactly as it occurred to me shortly before my departure from Zurich.” He ended his letter with an important detail: “But I must be off to the library, otherwise it will be getting too late.” Confirmation of the work he was doing there came the following week, on 10 April: “Last week I studied electrochemistry and chemical reactions from Michele’s ‘Ostwald’, and the electron theory of metals in the library.” This library, which was likely to have been close to his home, must therefore have held the Annalen der Physik in which Drude’s articles on the electron theory were published. At that time, the only library in Milan where this journal could be found was the library of the Lombard Institute Academy of Science and Letters. It also held the Annalen der Physik und Chemie from before 1900 and the Beiblätter zu den Annalen der Physik, which Einstein also read.

The Lombard Institute was founded in 1797 by Napoleon Bonaparte on the model of the Institut de France, transposed to the setting of the Cisalpine Republic. Its first president was the celebrated physicist Alessandro Volta. Einstein may have been able to access the library (which today holds 450,000 books) through the offices of Giuseppe Jung, Michele’s uncle, who was a member of the Institute. The library was located in the Brera Palace, around five hundred yards from the Einstein residence in via Bigli. Jung lived mid-way towards it, in via Borgonuovo. Although the Brera Palace is mentioned by Einstein’s son-in-law Rudolf Kaiser in his 1931 biography, its significance is thus greater than that writer suggests: “Milan was a paradise of freedom and beauty […]. For the first time in his life, [Einstein] studied the plastic and graphic arts: The Last Supper of Leonardo da Vinci at Santa Maria delle Grazie, the collections at Brera – a world of classical beauty!”

Having pinpointed the place where Einstein was studying, it becomes easier to understand his academic orientation in the light of the articles he was able to consult there. For example, on 31 January 1901, the Institute library acquired a copy of the Festschrift for Lorentz, published in Volume V of the Archives néerlandaises des sciences exactes et naturelles. This contains articles written in homage to the great Dutch scholar by around sixty international scholars to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of Lorentz’s doctoral dissertation. Aside from the article by Poincaré on La théorie de Lorentz et le principe de réaction, which Einstein, who was at that time interested in Lorentz’s theory, could have discovered when he was in Milan in April 1901 (and which he would cite in 1906 in order to dissociate himself from it), it was probably first and foremost the article by Max Reinganum, Sur les forces moléculaires dans les gaz faiblement comprimés, that engaged his attention in relation to his dissertation. Indeed, in the first place, in December 1900, Mileva informed her friend Helena Savic that Albert would submit his dissertation by Easter. Then, in his letters of 14 and 15 April 1901 to Marcel Grossmann and Mileva respectively, Einstein expressed his interest in extending his research into molecular forces to gases. In so doing, he came up with the bold hypothesis that the size of molecules was not a factor and that molecular forces were analogous to gravitational forces. This subject matter, these hypotheses and a similar vocabulary can be found in the Festschrift article by Reinganum, an author who was, moreover, known to Einstein. It is thus possible to see how his bibliographical work fed into his scientific research, reinforcing his own ideas or suggesting new pathways for him to follow. In December 1901, Mileva would tell her friend Helena that the dissertation was ready and that it concerned molecular forces in gases. But this topic was finally abandoned in February 1902 and it was not until 1905 that Einstein submitted his dissertation, on molecular dimensions.

"Having pinpointed the place where Einstein was studying, it becomes easier to understand his academic orientation in the light of the articles he was able to consult there."

conclusion

This research has revealed the young Einstein’s enthusiasm for and his interest in various parallel topics then current in the scientific world, and the advantages he gained from his family circumstances. These enabled him, as a very young man, to make contacts among the most important figures in the electrotechnical and university spheres. He was thus able to benefit from qualitative explanations of the phenomena of capillarity or Brownian motion (for example) and from lively discussions with his friend Michele Besso. The latter clearly played a significant role in his life from 1895, when he first attempted to gain admission to ETH Zurich. Michele continued to admire his protégé’s brilliance and determined character but remained in the background. The bibliographical research that Einstein carried out in the library of the Lombard Institute allows us to observe how the thinking of the young physicist evolved. The Institute would not forget and in 1922, just before he received the Nobel prize, would make him a foreign member of the academy, at the particular instigation of Giuseppe Jung.

*Translated by Emma Mandley / KennisTranslations

The collected papers of Albert Einstein, Vol.1, The early years, 1879-1902, ed. John Stachel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987)

Albert Einstein, Michele Besso: Correspondance: 1903-1955, ed. and transl. Pierre Speziali (Paris: Herman, 1979)

Christian Bracco, Quand Albert devient Einstein (Paris: CNRS Editions, 2017); translated into Portuguese as Quando Albert se tornou Einstein (Lisbon: Bizâncio, 2018)

Share article