1.

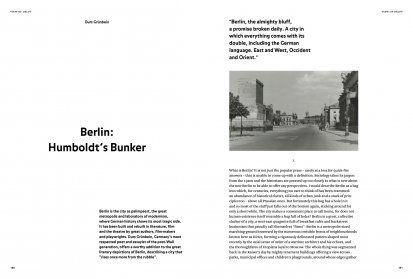

Berlin is the city as palimpsest, the great metropolis and laboratory of modernism, where German history shows its most tragic side. It has been built and rebuilt in literature, film and the theatre by great authors, film-makers and playwrights. Durs Grünbein, Germany’s most respected poet and essayist of the post-Wall generation, offers a worthy addition to the great literary depictions of Berlin, describing a city that “rises once more from the rubble”.

What is Berlin? It is not just the popular press – rarely at a loss for quick-fire answers – that is unable to come up with a definition. Sociology takes its jargon from the 1920s and the historians are pressed up too closely to what is new about the new Berlin to be able to offer any perspectives. I would describe Berlin as a bag into which, for centuries, everything you care to think of has been crammed: an abundance of historical clutter, all kinds of urban junk and a stack of principles too – above all Prussian ones. But fortunately this bag has a hole in it and so most of the stuff just falls out of the bottom again, sticking around for only a short while. The city makes a convenient place to call home, for does not human existence itself resemble a bag full of holes? Berlin is a great, collective slacker of a city, a west-east quagmire full of breakfast cafés and backstreet businesses that proudly call themselves “firms”. Berlin is a metropolis-sized marching-ground traversed by the numerous invisible fronts of neighbourhoods known here as Kietze, forming a rigorously delineated pattern shaped most recently by the axial sense of order of a wartime architect and his echoes, and the thoroughfares of Utopians loyal to Moscow. The whole thing was segmented back in the Kaiser’s day by mighty tenement buildings offering a view across parks, municipal offices and children’s playgrounds, around whose edges gather unemployed fathers who, just two or three generations ago, would have been forced to play soldiers but are today reading the newspaper or fiddling with their mobiles. Berlin was at the outset a military and early industrial complex, both the breeding-ground of Weltgeist, this mysterious shaping force of history, and the place from which it was most effectively banished; at all times essentially a stone city, it was once the stronghold of the employee, “Central Europe” as the headquarters of objective realism, at one time the jellyfish-like capital of an expanding Reich, later a heap of rubble for lost souls and today their federal haven, with a moth-eaten sofa by the roadside and a gutted Palace of Culture. And always something going on deep underground, in the labyrinth of bunkers and U-Bahn tunnels, latterly a refuge of pounding techno parties. Yet no sooner do you emerge onto one of the vast empty lots than the walls tumble away to reveal a starry night and the following day the most distinctive – Prussian – blue of all Germany’s skies. Berlin is a vacuum with the knack of filling itself up all over again with whatever possesses sufficient entertainment value. The key thing is that it is the capital city, the key thing is to be right in the middle of the temporary nowhere, where the music plays – part-Metropolis, part-Jericho. Berlin, the almighty bluff, a promise broken daily. A city in which everything comes with its double, including the German language. East and West, Occident and Orient, a pair of conjoined twins with little in common, only the transport network and the name; and anyone who likes all this talks about it the way I do. Because what is modern about it is precisely that there’s nothing to hold on to here. And now for a confession: I own up to having an erotic relationship with the names of cities. You only have to let the word Rome (or Moscow, New York, Tokyo) pass your lips and that sets me off. Every city has its formula for arousal, its own euphoria factor, which can only be sensed by the nerves, in films and novels, in photography, painting, music or – poetry. “The swindle that is Berlin differs from any other swindle in its splendid shamelessness,” wrote Bertolt Brecht to an acquaintance in 1920. And in this he is seconded by Walter Benjamin, “Berlin is a wonderful instrument on the condition that you play on it without giving a damn.”

"Berlin, the almighty bluff, a promise broken daily. A city in which everything comes with its double, including the German language. East and West, Occident and Orient."

As Walter Serner did not quite say, nowhere else but in Berlin, this paradise for confidence tricksters and hot air salesmen, could the Last Temptation have taken place. The only stylish thing for the two halves of the city to do amid all this unstylishness was to continually kick up an enormous fuss about something and then bore each other to death – with iron endurance and a torrent of subsidies. For Heiner Müller, one of the city’s last stoic bards, Berlin was literally – “the ultimate”. The place where German history took the worst possible turn and ended pitifully in a satanic fart.

“It’s impossible to recover one’s health in Berlin”, wrote Ernst Jünger to Gottfried Benn in the 1950s. Only Benn was no longer in a position to agree because he had long been terminally ill by the time the comradely tip reached him. Benn, your typical Berlin resident, leading a publicity-shy back-courtyard existence, averse to travel and pomp, a regular at the bar on his street corner (an extension, in a sense, of this doctor-poet’s own surgery), was responsible for writing some ground-breaking poems about the city. A speech he gave fifty years ago, during the Berliner Festwochen, on the subject “Berlin between East and West”, contains the provocative observation that “West Germany is foundering culturally because Berlin no longer exists.” This is followed by a sentence that encapsulates in a single image the lost or submerged nature of the city: “Berlin,” he proclaimed, “is buried in the jungle like Angkor and trips there are expeditions undertaken partly out of curiosity and partly out of nostalgia.” This is a voice from the days of the Four Power Agreement, when one part of the city was an island provisioned by the “candy bombers” and the other the parade ground of an empire that stretched all the way to deepest Mongolia. For a long time, this rearward part, the territory or camp open to the East, was the only one accessible to me. But division and provinciality on one side and the other, the Atlantic outpost behind enemy lines and the desert fortress of the Mark Brandenburg are all in the past now, forgotten in the name of a world city routine that wants nothing to do with nostalgia and only as much to do with the future as can be marketed to tourists. Here my thoughts return to Heiner Müller, who, like Benn and Brecht, died in Berlin (that was ten years ago) and whom I got to know as the last link to the highly-wrought big-city literature of the last century, its political convictions and artistic overstrainings. Despite all the warnings, this city continues to attract artists, the aspiring and the fully formed, as well as those who make a living from both, the movers and the shakers, the curators and the croupiers. Without anyone really holding the bank, but either at their own expense or at someone else’s, they all join in the game here for a while. And it was no different for me. Like them, I turned up in the city one day with high-flying hopes of finding a world in Berlin and of finding myself in that world.

"For Heiner Müller, Berlin was literally – “the ultimate”. The place where German history took the worst possible turn and ended pitifully in a satanic fart."

René Burri, The Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedachtniskirche, 1959

© Photo: Magnum Photos

2.

Nowhere can I drift into a daydream as sublimely as in Berlin. It is the city in which I have spent the greatest portion of my life, the city I know the best, despite its many building sites continuing to play tricks on the locals. It was familiar to me from the moment I entered it thirty years ago over Warschauer Brücke. Since then it has been like a bedroom in which you have already spent a thousand nights and are intimately acquainted with every centimetre, from the ceiling moulding all the way down to the skirting board, even in the dark.

Daydreaming begins when there are no more surprises. At that point the gaze is free to notice the transitions between the internal and the external – those border crossings of which Berlin, during its days as a walled city, had its share. For the rest of the world back then, Berlin was a city of secret openings. There were barbed-wire-garlanded gateways and kilometre-long beaches of Brandenburg sand luring people to leap into the death strip. There were escape tunnels, and bridges on which, in the cloak of night or fog, spies and political prisoners were exchanged. All these sluices and shadow zones have now disappeared, along with the massive concrete barrier that once held West and East in an equinox-like equilibrium. The crossing points, however, have survived: you just need to know where to find them. Natives of the city can thank its former division for a pattern of behaviour that orders their reveries even by day. They take their bearings from the cracks in the tarmac, from the landfall-like demolition precipices. With a practised eye they follow the course of former waste land, gaps in the development schemes, and will not permit themselves to be led astray by the big-city advertising. With them go the dreams of a shattered, bleary-eyed city – a city that rises time and time again from miscarried development projects. One architectural eyesore succeeds another; the city is continually falling pregnant with some megalomaniac project or other. Happily, amid this eternal improvisation there are orientation points that reliably regulate the dream-traffic, allowing you to follow the historic ground plan once more and drift through the Prussian city of stone.

"Here even the trees are historic. In winter they look as if they have been through a war. Their ruptured, furrowed bark makes one think of shrapnel."

The many foreign languages that caress the ear wherever you go are another, not insignificant, factor that contributes to the dreaming. Naturally English predominates, but all the European tongues and some Oriental ones are forever in the air. Meanwhile, Russian provides a kind of basso continuo: it can be heard on the major boulevards whose edges are lined with Mercedes limos – highly polished coffins out of which an astonishingly spry corpse will leap all of a sudden. It can be heard in the vicinity of the exclusive boutiques and on department store escalators. Around one of the Currywurst stalls swarm Chinese, all of whom, by some miracle, speak Chinese. Only the Turks fire out phrases at one another in – generally broken – German. The effect of the different languages is that you remain forever the outsider, the unbeliever. A ride on the U-Bahn, squeezed in on the seats among a crowd of dignified bearded men, takes you to a far-off place, a kind of bazaar where different cultures are thrown together. Somewhere or other you step into the daylight, squint into the sunshine in search of a familiar church tower, and instead catch sight of a tenement building that resembles all the others and yet is somehow different. The small difference is enough to kindle yet another daydream.

René Burri, Kreuzberg, 1959

© Photo: Magnum Photos

3.

Look out of a window somewhere and history hits you in the face: that is Berlin. Stand on one of the many balconies of one of the city’s many tenement blocks and the stone city comes at you with monuments, street signs and façades of buildings from which the Weltgeist squints back at you. The man who coined the term, which denotes an invisible, history-shaping force that cuts right across the physical world, also lived and worked in Berlin (where else?), occupying the chair of philosophy at the university. It was a fitting theory for this historic crime scene. From here the shock waves radiated to the outermost fringes of the continent and back again, smashing the den of thieves and ploughing up the ground until the city was nothing but an enormous heap of rubble.

Here even the trees are historic. In winter they look as if they have been through a war. Their ruptured, furrowed bark makes one think of shrapnel, but it is only in this place that such a thought comes to mind, even though the wind and frost leave their mark on trees elsewhere too. Nevertheless, in Berlin the wind whistles around the corners of buildings more icily than in other places and the November rain lashes through the bare branches as if blown directly from the Russian Plain.

At such a time of year a word like Volkspark is no more than a euphemism. But in summer the green hill that rises up in this “people’s park” entices the population to come and flirt on outspread bath towels. Naked flesh shimmers through the undergrowth, while in winter it is as a toboggan run that the park pulls people in. But look: concealed below it is a mountain of rubble, an uncanny, blood-soaked subsoil churned up by demons. You live in the immediate vicinity for years and then, as your dog snuffles around the foliage, a grey object is exposed, your foot strikes shattered concrete and a steel girder protrudes from the ground. The changing seasons on this rise gladden the hearts of walkers only for them to discover sooner or later that a flak tower-cum-bunker once stood here, storeys-high and as solid as an Assyrian temple. This structure split into two halves when it was blown up after the end of the war. In the chaos, Renaissance sculptures and paintings from the Prussian collections disappeared, never again to be seen. Poor Giovanni Bellini, what happened to your Madonna and Child? Poor Luca Signorelli, what fate befell your Pan and his Attendants? The list of artworks lost from the Friedrichshain flak tower is a long one.

A narrow-gauge locomotive was deployed at the site for a while, carting away the rubble in steel wagons. During the hot summer of 1945 this engine laboured through the dust-clouds of the pulverised city, out on a limb in the eerily deserted park. But the rubble would not be carried away. Even as a ruin the flak tower continued to resolutely hold its position. The only option was to bury it, to conceal it beneath a layer of camouflage like a nuclear reactor after a disaster. Eager Lilliputian women – a large proportion of the island’s male population having been taken prisoner of war by the Soviets – got down to work, whole legions of industrious females clutching shovels, the odd tracked vehicle dotted among them, and they did not stop until the mark of shame had been completely covered over with earth.

At night, and particularly in moonlight, the silhouette of the ridge of the hill hints at the monstrous architecture underneath. Berlin’s tower-bunkers seem to have been modelled on the Staufer fortresses in Apulia, geometric showcase structures, menacingly modern, of which the crowning glory is the Castel del Monte in the hinterland of the port of Bari. In Berlin, however, the building material was not the light, sand-coloured limestone that feels pleasant to the flat of the hand, but grey, seamless, artillery-proof cast concrete, metres-thick reinforcement encasing a steel skeleton. These were bulwarks that no Mongol hordes could have swept aside. Even heavy artillery was incapable of doing more than nicking the elephant skin.

Flanked by a low wall, the path spirals its way to the top. There, fragments of the former flak platform jut out even now from the masses of heaped-up earth. Their unwieldy forms defy all attempts to make them disappear, to kill them off. From the summit, the eye sweeps over the entire district. This would be a good spot for a homicidal maniac to hunker down. With all the calmness of the anti-aircraft gunner, he would be able to get the various targets in his sights – to the east the station and new Rockarena, to the west the residential district of Prenzlauer Berg. To the south, the ball of the television tower, marking the location of Alexanderplatz, would make a good practice target for the gunman to get his eye in.

Three such installations once stood in strategic locations in Berlin, towering fortress-like over their surroundings, a constant reminder of the population’s helplessness, menacing but at the same time offering refuge. That in the Zoological Garden, having provided more than twenty thousand people with shelter during the war in the air and having also accommodated the bust of Nefertiti, was blown up; that at Friedrichshain – where treasures from the Berlin museums were also stored, and where the SS fought to the last, wall niche by wall niche – was buried. The only one of these structures (its north flank, at any rate) to have survived is the Hochbunker at Humboldthain in the old working-class district of Wedding, close to the former AEG works with their huge and impressive turbine hall.

Steps lead up to it and the flak platform is surrounded by railings on which children like to do gymnastics, occasionally coming a cropper. The kick they get is just as much a part of it all as the lugubrious atmosphere that radiates throughout the rest of the park from the bunker. The shadows are longer here where there is a gash in the green lungs. “Local recreation site” is a pretty expression. But contaminated ground lies underfoot, the burdensome legacy of a fallen tyranny that seems to be far from dead and buried, and not to sense this requires a degree of mindlessness. When coming in to land at Tegel airport, it is occasionally possible to catch a glimpse of the grey mass of the bunker between the sparse pines in the snowy park, and an uplifting sight it is not.

These colossi were an architectural expression of megalomania, and the real contribution of the Third Reich to Berlin’s modern urban culture. There was clearly something of the operatic about them, something of the loud-mouthed director, of the empty brag. Indeed in this final stage, the battle of matériel, measured in cubic metres of concrete, two hundred million of which are believed to have gone into the building of bomb shelters up and down the land, was the only form that culture now took. It is still painful, standing in front of these concrete cubes, to think of Germany’s estrangement from the world, the narrow-minded, parochial nature of National Socialism’s wartime planning, the tendency to seal oneself off and curl up into a ball, and the enormous collective claustrophobia. From Humboldt things went downhill until everyone had gone to the dogs, landing themselves the shabbiest of death cults and caught in their own death-trap of flak towers and bomb shelters.

And as I have already said: that is Berlin, the combat-weary city that knows no peace. There is nowhere here that has not already been shat on by the Weltgeist. Here history knows no let-up. It is here, amid all the delusions of grandeur, that the nocturnal ghosts gather. The ground can open up just like that, causing you to stumble into old death pits. Out of the grey sky comes the sound of bells, to which no one pays any attention. It is night-time, you step out onto the balcony, darkness has swallowed up the contours of the flak mound opposite. With its rows of parked cars, the street bordering Volkspark Friedrichshain lies still in the yellow glow of the “whip lights” that once illuminated the sandy death strip.

*Translated by Richard Elliott / KennisTranslations

Share article