Rosi Braidotti is an Italian-Australian feminist (she was born in Italy in 1954, but grew up in Australia and studied philosophy at the University of Canberra) with a prominent intellectual career in the field of women’s studies, though for a long time she was only known and recognized within specific niches. She helped found a European network of women’s and gender studies, ATHENA, which received the Erasmus Prize of the European Commission, in 2010. Her philosophical work is closely linked to a strong political and social activism for women’s rights, in Europe, and to her pioneer role as founder of a women’s studies department at Utrecht University, in Holland, which she directed from 1988 to 2006. Her collaboration with radical feminist magazines began in the mid-1970s in Australia, which she left in 1978 to move to Paris. There she found a cultural environment permeated with post-structuralist philosophy, often labelled the ‘philosophy of difference’, and the feminist generation that moved within that constellation (Luce Irigaray, Hélène Cixous, etc.). From that time of great theoretical effervescence, two figures have remained as points of reference in Rosi Braidotti’s project: Foucault and, above all, Deleuze (especially the Deleuzian reading of Spinoza). We say ‘project’ since that is the word commonly used by Braidotti to refer to her theoretical and philosophical elaboration of the concept of nomadism, in a trilogy that began in 1994 with Nomadic Subjects. Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory and was followed by Metamorphoses (2002) and Transpositions (2006). Subsequent to that trilogy, but perhaps representing its apex, we find the more recent The Posthuman (2013). Braidotti’s ‘nomadic thought’ is highly engaged with the present. The concept of nomadism (whose genealogy can be traced back to Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the rhizome) provides Braidotti with an instrument capable of reading the present, almost charting it, since it is endowed with great analytical capability and critical content. The philosopher starts out with the formulation of the nomadic subject and extends the critical potential of nomadism (in short, a critique of fixed entities and identities: for example, Eurocentrism) to culture, politics, sexuality, and ethics. In this interview, we can easily conclude that Rosi Braidotti’s ‘nomadic feminism’ distances itself somewhat from gender theory and, consequently, from the American philosopher who has taken the gender issue furthest in terms of theory and with more profound effects: Judith Butler. Braidotti strives to reflect on sexuality beyond gender, a sexuality that is not disembodied and that takes into account the materiality of bodies and their social, political and subjective inscriptions. At the same time, she defines the condition of certain fundamental categories of advanced capitalism.

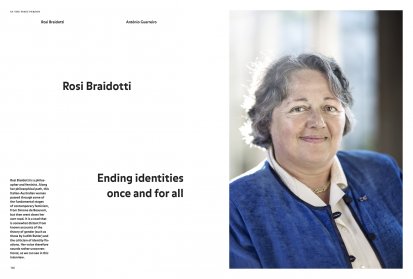

Rosi Braidotti is a philosopher and feminist. Along her philosophical path, this Italian-Australian woman passed through some of the fundamental stages of contemporary feminism, from Simone de Beauvoir, but then went down her own road. It is a road that is somewhat distant from known accounts of the theory of gender (such as those by Judith Butler) and the criticism of identity fixations. Her voice therefore sounds rather unconventional, as we can see in this interview.

Rosi Braidotti

© DR

ANTÓNIO GUERREIRO You have written a text about your intellectual trajectory entitled ‘Untimely’ for a collective book on your work (The Subject of Rosi Braidotti. Politics and Concepts). From the outset, the title suggests your claim to unseasonable thought. Yet, providing conceptual tools for reading the present is the task that motivates you…

ROSI BRAIDOTTI To begin with, there is a contextual element: this text was written as an afterword to a volume of commendation, celebrating my sixtieth birthday. There I made a kind of Blanchot-inspired commentary on my existence, as if I were not here anymore, as if the subject had already been evacuated. It was not only a stylistic exercise, but also a very complex and painful intellectual one, allowing me to trace the central lines of my work and research, which I was aware of at the conceptual level, but maybe not so much at the emotional level. This untimely thought consists of swimming against the current, i.e. in opposition, but at the same time I want it to be affirmative and not nihilistic or negative. I owe a lot to the generation of brilliant philosophers with whom I studied: early Foucault, but mainly and very strongly, Deleuze’s thought and some of Luce Irigaray’s, before she became too spiritualistic for my liking. Especially the revision of Spinozism, by Deleuze and Guattari, and early Negri had a big impact on me. That spirit that passes through Nietzsche and Spinoza, reinterpreted by French philosophy from the 60s and 70s and revisited by a feminism engaged with the present, with the world as it is, can serve as a framework for my project: fully facing the present; a present that isn’t just the current one, but is also virtual, always a becoming. It looks both at the past and at the future. I think that this engagement with women’s rights and human rights lies at the heart of this complex relationship with resistance.

AG You arrived in France in 1978, coming from Australia, and found the feminist generation concerned with post-structuralism and the philosophy of difference. But then you distanced yourself from that and forged your own way. Could you describe that process?

RB It is very complex. In 1978 we were living the aftermath of the events of May 68. In 1980, François Mitterrand came to power, signalling the end of the militant left. I went through that transition period when, as a result of the partial failure of May 68, activists, intellectuals and teachers were looking for alternatives to the revolution that had not succeeded. And I think that it is very important. Almost no one celebrated the fiftieth birthday of May 68, the revolution that, despite failing, changed the world and led to a search for alternatives within philosophy, for example a return to Spinoza and a rejection of Hegel and a particular brand of Marxism. It was a moment of transition, mutations and changes that saw the left rise to power. And, in that sphere, the radicalism of the 1970s was revised by many groups. In the case of feminism, it was strongly influenced by psychoanalysis. What happened in France, both the women’s and the psychoanalysis movements, has allowed me to understand what is happening right now in terms of identity, for example, what identification is.

AG Today the concept of ‘identity’ has become pervasive…

RB Yes, we talk a lot about identity politics, but the questions of identification, how imagination works, and how the unconscious process structures the social and the phantasmatic and delirious planes have been trivialized. There was this spirit of seriousness and sobriety that we took from psychoanalysis and that caused many splits in the women’s movements. In 1970, in France, there were Lacanian feminist movements with a lot of differences between them, especially concerning how to approach the relationship between the structure of the unconscious and politics. The whole Lacan phenomenon hinges on that, ultimately causing violent theoretical and personal conflicts among French feminists, between Cixous and Irigaray, between Cixous and Beauvoir – in short, a whole series of quarrels. The feminism of difference has never existed. It was invented in translation, when the Americans opportunistically discovered these new texts and translated them as representing ‘new French feminisms’. To some extent, they did the same thing to French philosophy, by calling it ‘French Theory’ and thus killing what is alive and creative. It is a question of marketing. Americans invented a ‘feminism of difference’ that has never existed. There is a variety of ways of linking social reality to the phenomena of the unconscious, to identities. We just have to draw a comparison between Kristeva, a right-wing Lacanian, and Irigaray, a left-wing Lacanian, to arrive at two completely different worlds, though both have at their core the extremely patriarchal Lacanian conceptual structure, where everything revolves around the phallus and the commandment ‘do not question my phallus’ or there will be chaos, anarchy and psychosis. My impatience with this thought was immediate. When I was working with Luce Irigaray, I attended Deleuze’s seminars, and Deleuze critiqued Lacanian thought, alongside Guattari, in Anti-Oedipus.

AG And it was with Deleuze that your project of a feminist nomadism started?

RB It is essentially a critique of fixed, rigid and strong identities, since I encountered them in feminist movements as well. No political movement is safe from a fascination with power, and even a genius like Simone de Beauvoir drew on Hegelian and Marxist thought structures, or on strong identities and subjectivities. Today, people have grown tired of so much fluidity and there has been a return to fixed fascist structures. And that happens also with the left, which is not exempt from little dictators. I have witnessed that totalitarian drift within the so-called progressive and radical movements. The idea of inquiring into the process of change and into complexity, multiplicity, movement and the relationship with others, all of that seemed absolutely essential to me. And essential also with respect to another project that is dear to me and that is going through a very difficult moment right now: the European project. Nomadism is a critique of nationalisms, including the European nationalism that is at the core of a certain idea of Europe as the centre of the world, the heart of civilization, the place where the Enlightenment has led humankind towards great progress, through reason and science. This is a very self-indulgent and self-aggrandising discourse, while the colonial and imperialistic implications of this narcissistic Eurocentrism are often glossed over. On the one hand, we deny that our wealth and well-being is a product of the empires that we have built and that we continue to defend; on the other hand, we find a discourse that places us at the centre of the world and distances us from the misery of the world. This is a completely bipolar, psychotic stance, which is active today in the discourse about immigrants and refugees, where ignorance goes hand in hand with arrogance. Sometimes people are even oblivious to the fact that we had empires.

[...]

Share article