I walk up to the door, massive and closed. I feel like I’m entering a place of worship, immersing myself in the darkness of space. I climb the stairs, and each step brings me closer to what I’m anxiously expecting. The hum of the outside world becomes ever more distant, until it fades into no more than a distant memory, and then not even that. When at last I reach the fifth floor and enter the room, the noisy world has receded to nothing. Silence falls, time stops. Nine expectant figures, each accompanied by a dog, await me in a circle of fire. They seem to me to give off a blue light, although they’re made of soft white limestone. Arms crossed, they wait for time to reveal the enigma of which they are the seed. They are made of dust, dust accumulated over the centuries. I am small, very small, they are enormous and silent, on their pedestals. Maybe they are self-portraits of a vanished mankind, models in a pose with no beginning and no end, keeping watch for us. I understand that their vocation will always be to create a space of beauty inside others, inside those who look on and converse silently with them. “They fill others with beauty,” I think. “Might that be my vocation too?” To my wondering eyes, each of these outlines lies between a kouros out of its time and the Ange du Méridien at Chartres Cathedral, his mouth made of a hundred mouths. These silent, still, absent figures will stay within me for ever.

They are pieces that exist outside time, or in a very ancient, archaic or archaeological time: a time without time. Only a few will manage to hear the voice of their beauty. Their immobility, a state of waiting that appears to belong to fragmented sleep, accentuates the love that we should all feel for the suspended moments we experience, so distractedly. These works stop us forgetting that we have to stop time to see beyond the world of appearances. To communicate with things, we have to enter into them, to become them. Even if just for an instant.

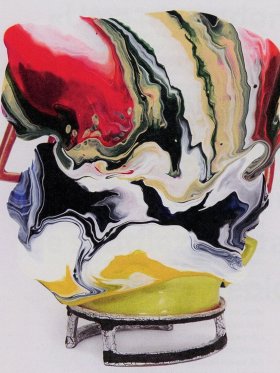

All of Manuel Rosa’s sculpture shows us that beauty is a consequence of duration and persistence (and, consequently, of contemplation). So his work stands outside this world of speed and haste, where superficial images and information flash past, making us confuse beauty with fleeting attraction, the inner pulse with a mere gasp. The beauty that Manuel Rosa seeks and offers us is made of silence and the sediment of time. Only here is beauty at one with truth. This is also why these stark, timeless figures, these canoes, containers and empty houses, seem to come from another age, not an age that fed on itself out of emptiness. They carry within themselves architectural structures which already lay in ruins. The hieratic nobility that these pieces exhale also speaks to us from its ability to resist (or to survive): I see the work of this sculptor as an immense shipwreck, from which only the debris reaches us. This world speaks to us, radically, of a world facing extinction.

Death is not always a narrow door we have to pass through, sometimes it is a path we follow, when we know we are witnessing the end of something. At the end of the path will be memory, for as long as there is space for it to make sense. Some of these sculptures simulate the detail fossilised in our innermost terror, the way we face the end. The simplicity with which arts seeks to heal the wounds of death...

How many centuries enclose within them the gaze of millions of eyes, which come together in a single gaze, across the years, in a complex winding line that finds its way to us? This trajectory outside time, or parallel to it, is where Manuel Rosa put his hands to work. In his closest connection with the Earth, this artist models his forms in clay. Other times, he lets them emerge from fire and the incandescent earth, taking on an existence in iron or bronze. But his starting matter is the absolutely static weight of stone. I see the limestone as an accumulation of sands, in the immensity of years without beginning or end. How many thousands of years does a rock take to be formed and how many does it take to become a pebble? How many centuries does it take sand to accumulate, with fossils and crystal fragments, and form a block of limestone? This is the time- and millennia-old stone from which these silent figures that await and confront us emerge. Made of the sediment of dust, made of the dust of time. Every time I visit these sculptures, I still sense in the air the dust hanging in the air of the sculptor’s studio. The same film covers the faces before us, fixed for eternity. I can feel them cling to the dust of time.

Manuel Rosa’s sculptures are statues which were removed from places of worship when there was still a reason to have such places for people. In each of them I see the sad smile of a mute angel, his serious, severe face that duplicates the shadow of our eyes. I have grown accustomed to finding these serene and melancholy figures where I least expect them; they await me expectantly at the corner of a building, when you walk into a house, as our friends open the front door to welcome us. Over the years, they have been transformed, and have themselves become a house that welcomes me each time I visit them.

Manuel Rosa belongs to a time when it was still possible to believe in the figure and in figurative representation in art, using it in a believable and serious way that is rare to find today. That is perhaps why his work presents itself, today, with a disconcerting serenity that is now strange to us, that is no longer familiar. The gift that this artist offers us is the possibility of discovering works that make the world around us stop and which, for a few moments, silence the noise and lead us to a place of contemplation and almost melancholy delight.

Discreet, but always present and generous, this artist brings with him his enormous love for words, literature and the beauty of books. His tranquillity is synonymous with humanity, discretion and rigour. Manuel Rosa has been taking care of others, of all his fellow artists, writers, poets, photographers and film makers who still believe that a love of books might perhaps be the way to perpetuate the ephemeral quality of knowing and questioning. He does this with the greatest care, painstakingly and scrupulously so that the final result is the finest and simplest written record of the idea that others thought of building. In essence, like his sculpture, his writing sets out to present us with works that make the world around us stop, and silences, for a few moments, its senseless noise, taking us to a place of delight, where we think and read. A space without a body, withdrawn from the world, that seems increasingly rare. Perhaps the fear that people are at risk of losing books, and the precious hours given over to reading, is the reason for his long absence from his studio and his sculpture. In any case, the same wish to offer such a rare place to people, which the work of the sculptor and the publisher have in common, is such a generous gift that our thanks cannot find expression in the words of a text.

I walk up to the door, massive and closed. I feel like I’m entering a place of worship, immersing myself in the obscurity of space. I climb the stairs, and each step brings me closer to what I’m anxiously expecting. The hum of the outside world becomes ever more distant, until it fades into no more than a distant memory, and then not even that. When at last I enter the room, the noisy world has receded to nothing. Silence falls, time stops. Dozens of expectant figures await me, accompanied now by other faces and shadows forming several circles of fire that intersect serenely. Canoes, debris of boats that never sailed, igloos, bones, jawbones, tunnels, huge funeral urns, skulls, heads, bowls, circles... I feel like I’m in the storeroom of a museum, inhabited by countless statues and lost remains, archaeological finds before being discovered...

Then at last I realise I’ve come back to the place of worship that these nameless, untitled images never left. They continue to give off a light, despite being made in soft white stone, limestone (but also in fired clay, plaster, bronze, glass, coal, foundry sand, cast iron, plaster, wood...). The time that passed can perhaps be measured in hours, days, years... in hairs that turned the colour of moonlight, but I’m still small, very small, and they’re still enormous and silent. Perhaps they are self-portraits of a whole vanished humanity. I understand that their vocation will always be to create a space of beauty inside others, inside those who look on and converse silently with them. “They fill others with beauty,” I think. “Might that be my vocation too?” To my wondering eyes, each of these outlines lies between a kouros out of its time and the Ange du Méridien at Chartres Cathedral, his mouth made of a hundred mouths. These silent, still, absent figures will stay within me for ever.

*Translated by Clive Thoms

Share article