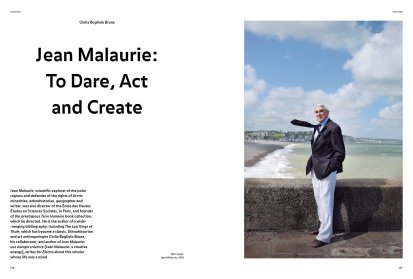

Creative energy at the service of an ecological humanism, explorer of frozen deserts, anthropo-geographer, successful writer and publisher, Jean Malaurie (Mainz, 22 December, 1922 – Dieppe, 5 February, 2024) traversed the 20th century as a retro-futurist, appropriating Terence’s maxim: Homo sum humani nihil a me alienum puto [I am man, nothing that is human is indifferent to me].

A prolific author of works that are classics nowadays, from The Last Kings of Thule to Hummocks, from Ultima Thule to The Call of the North, from Letter to an Inuk from 2022 to Oser, resister [To dare, to resist], Malaurie always promoted the construction of a civilisation of the Universal, multiple in its unity, multi-ethnic and rich in fruitful cross-fertilisation.

Awarded Grande Médaille of the Société de Géographie in 1997, Patron’s Gold Medal (Royal Geographic Society, 2005), UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador in charge of Arctic issues (2007), Commander of the Légion d’honneur (2015), Malaurie embodied the figure of the non-conformist and eclectic humanistic intellectual, unus et multiplex. On the day after his death, French President Emmanuel Macron paid him a vibrant tribute, remembering him as ‘[a] French writer of the Universal, a man who knew how to dare, to resist [...], a great scholar who traced the legend of the century.’1

Refusing, in June 1943, ‘the unacceptable Service du travail obligatoire (STO, compulsory work service) [and] the paramilitary collaboration Vichy sought to entertain with Nazi Germany’2, Malaurie, in his early twenties, chose his side and went into hiding. This courageous act of resistance constitutes the catalyst for a metamorphosis in his identity:

Share article