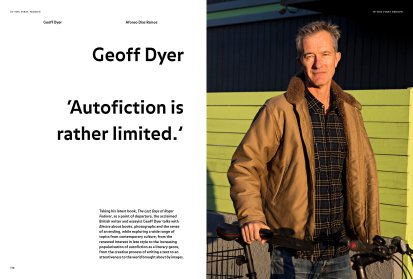

Geoff Dyer has published four novels and a broad range of non-fiction on subjects as varied as literary criticism, the First World War, John Berger, Tahiti and photography, which have been awarded numerous prizes in the UK and the US. A famously eclectic novelist and art critic, with a cross-referencing, genre-defying form of writing that has recently gripped contemporary literature, Dyer has mapped a route through the world of fiction, art, music and photography, always moving around different places and experimenting with many forms. He has analysed life on an aircraft carrier (Another Great Day at Sea), explored the lives of jazz musicians (But Beautiful), delved into his own failure to write a critique of D.H. Lawrence (Out of Sheer Rage), devoted a whole book to Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (Zona), and also penned a memoir-travelogue of sorts (Yoga for People Who Can’t be Bothered to Do It). Geoff Dyer’s collected essays and reviews (Otherwise Known as the Human Condition) won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2012, and his texts on photography, which have already led to three books, The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand, See/Saw and The Ongoing Moment, earned him an International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award in 2006. Kathryn Schulz has called him ‘one of our greatest living critics’ and ‘one of our most original writers’, Jan Morris described him as ‘perhaps the most brilliantly original practitioner of his generation’, and Zadie Smith dubbed him ‘a national treasure’. Born in England and educated at Oxford University, Dyer now lives in Los Angeles where he is writer-in-residence at the University of Southern California, and a regular contributor to various journals. In his latest book, The Last Days of Roger Federer (2022), Dyer has turned his focus to figures like George Best, Bob Dylan, Jean Rhys, Giorgio de Chirico, Friedrich Nietzsche, Eve Babitz and Adam Zagajewski, in a meditation about art and things coming to an end. He has talked to Electra about the current infatuation with autofiction, the experience of twilight

Taking his latest book, The Last Days of Roger Federer, as a point of departure, the acclaimed British writer and essayist Geoff Dyer talks with Electra about books, photographs and the sense of an ending, while exploring a wide range of topics from contemporary culture, from the renewed interest in late style to the increasing popularisation of autofiction as a literary genre, from the creative process of writing a text to an attentiveness to the world brought about by images.

© Matt Stuart

AFONSO DIAS RAMOS In your latest book, The Last Days of Roger Federer, the tennis star only gets a few mentions. Nietzsche is the major figure in your meditation on the arts and aging, which also includes Beethoven, Turner, Dylan... How did your interest in lateness come about?

GEOFF DYER It probably coincided with a sense of moving towards the twilight of my own creative life. To my astonishment, I was no longer 25. As in the Talking Heads’ song, it came as a great surprise to me, as it does to everyone. I was conscious of it proceeding in tandem with a sense of biological aging. But I was also conscious of having been interested in things ending from a surprisingly early stage. These manifestations make themselves felt sooner than one might think, which is why I thought it was nice to start the book with The Doors’ song, The End. As I say in the book, this was the last song on their first album. I also mention the experience that I had when I was 12, of one of the world’s greatest footballers, George Best, retiring when he was still close to his peak.

ADR You differentiate between lateness and lastness – you talk about last days, last games, last performances… What do you mean by this distinction?

GD It is a very important distinction, because there has been much talk of late style. This idea of late style has almost become an academic cliché. Beethoven is the classic example of somebody who very definitely had a late style, which is also his last style. Nobody would dissent from that. On the other hand, Beethoven’s last works seem to bring everything to some sort of conclusion. It is hard to imagine that he could have pushed things much further. When we listen to those late quartets, even now, they still blow our minds with how far out they are. But we can think of all sorts of examples of people whose last works, for whatever reason, came when they were really in what should have been their middle years. This happened with John Coltrane and Garry Winogrand. For both, the last works were in the midst of a transitional phase. You get the sense that there was plenty more to come. As we move the clock earlier on into people’s lives, we can think of many people whose last works are synonymous not with their late works, but with their first works, novelists who, for whatever reason, gave up after one book.

"Why should you give up doing something if you really love every aspect of it, even if you are not going to be doing it at your peak?"

Garry Winogrand, El Morocco, New York, 1955 © The Estate of Garry Winogrand / Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

John Coltrane in performance, 1962 © Photo: Bettmann / Getty Images

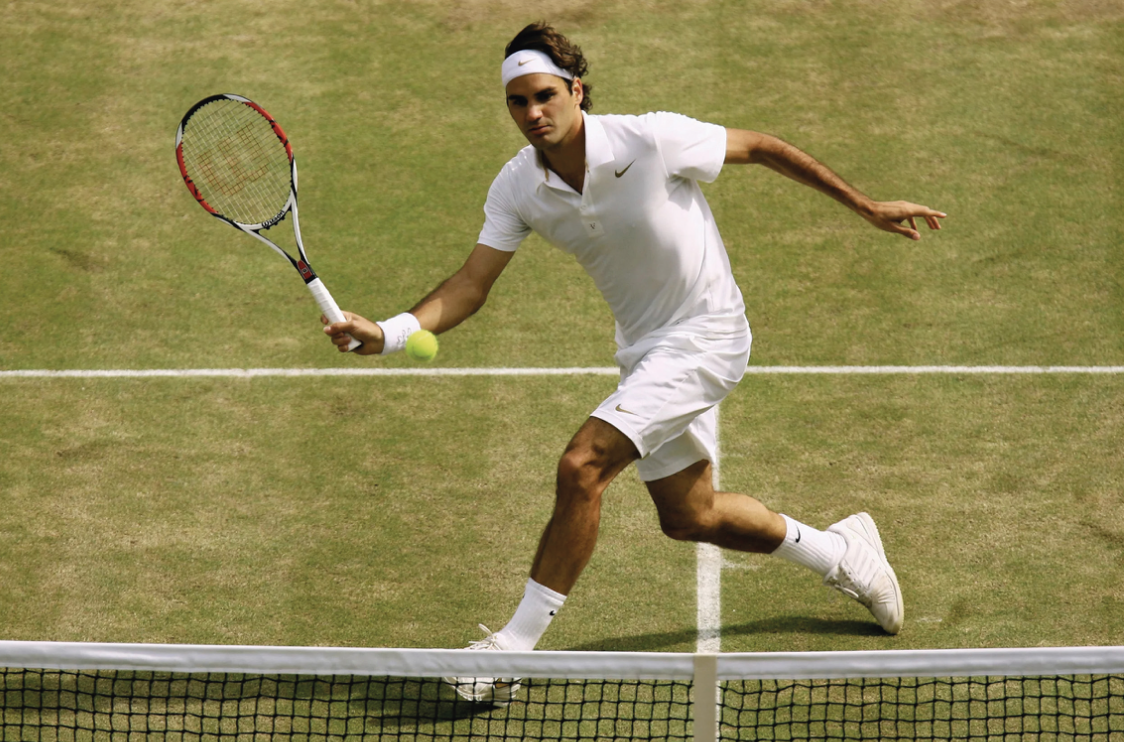

Roger Federer © Photo: Ian Walton

ADR Lateness was famously addressed by Theodor W. Adorno and Edward Said. But Said, for instance, wrapped it up in disenchantment. Your writing, on the other hand, seems to be getting more humorous.

GD I’m so glad you say that. I’m convinced that I’m getting funnier as a writer as I get older. That Said book was a great disappointment to me. It was an unfinished book, as he became ill himself, which is not his fault, but it seemed to me that the best bits of that book were when he did a synoptic appraisal of what Adorno had said. One of the things that I talk about in the book is when to embark on this discussion of lastness or lateness. Maybe Said just left that a little bit too late. But I should say that I never was besotted by Said in the way that some people are. He remained for me somebody who always sounded like an academic. I never fell for him the way that I did for other writers.

ADR On a completely different note: why did you go for Federer specifically? The twilight for elite athletes comes at an age before the dawn arrives for many intellectuals.

GD I was conscious of what you just said as well. But it has slightly changed now. The athletes are not drinking or taking drugs in the way that McEnroe and his friends used to. They can play into their late 30s. I used to see the life of an athlete as the best possible life, as it came to an end typically at about 30 – in other words, at the age that, typically, somebody publishes their first novel. It seemed to me that it could be the most glorious life: devoting yourself first to athletics and then to writing. I have a friend who was a pro surfer. It sounded amazing: going around the world, getting drunk and stoned with his friends, trying to fight off all the women who wanted to sleep with him. He looks back on that now and says it was fun, but that he should have written more. I always think: every writer that I know would have loved to have changed lives with you! The interesting thing about Federer is that, first of all, he had a very long twilight. There was so much talk about when he was going to retire. Maybe tennis is special in this regard. All that most footballers want is to keep playing for as long as they can. They love it. But tennis has driven some people nuts. André Agassi famously said that he came to hate tennis. But Federer seemed to like playing tennis, even if that meant playing when he was no longer going to win anything. And then came that lovely thing whereby, after we all assumed that he was never going to win anything again, he wins a further three Grand Slams. One of the reasons the book has his name in the title is because of that idea: why should you give up doing something if you really love every aspect of it, even if you are not going to be doing it at your peak? This overlaps with writers continuing even though the time of their best work might be behind them. That continues to interest me. I have been reading a biography of Walt Whitman, stressing how he went on revising and adding to Leaves of Grass for ages. But the period of his greatest creativity was compacted into less than a decade.

[...]

Share article