1.

The French philosopher and sociologist Geoffroy de Lagasnerie explores in this article why the object of his intellectual investment was never literature, but theory. This personal taste of his has provided him with a reason to analyse the attraction of theory, both in terms of knowledge and of libido.

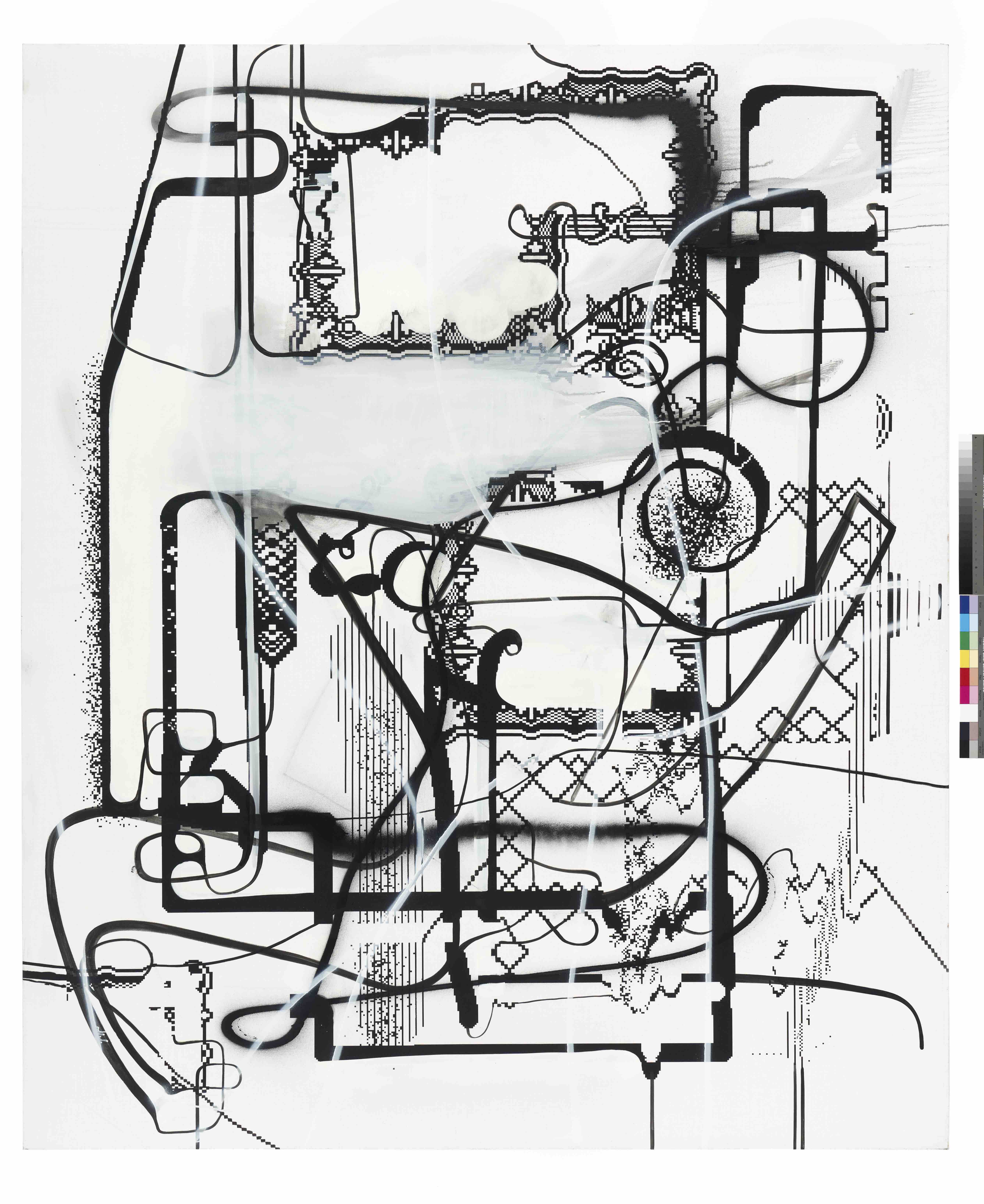

Albert Oehlen, Captain Jack, 1997 © Photo: Archive Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin, Paris, London / DACS / SPA, Lisbon

For as long as I can remember, ever since I was old enough to freely navigate culture and choose the books I wanted to read for myself rather than making do with the ones we had to read for school, I have always had a taste for theory to the exclusion of practically every other topic. Since I was sixteen or seventeen years old, my reading has focused almost entirely on philosophy and sociology, with occasional incursions into law and economics. I never really developed a taste for literature, novels, or poetry and I have always been rather disinterested in history, which is closely intertwined with literary writing and, as the most narrative of the social sciences, is also the most literary. My friends have never given me novels for Christmas or birthdays because, as they say, ‘there’s no point giving Geoffroy novels, he never reads them’.

As a teenager, I lived with my brothers and sister at my stepfather’s house (my mother’s new partner after she and my father divorced), which had an enormous library containing equal numbers of novels and essays. Whenever I was looking for a book to pass the time, I was always drawn to theoretical or political works, especially the texts by Marx, Lenin and Bakunin that my stepfather had had since his left-wing student days.

vMy preference for theoretical activity was not limited to books. It shaped my overall approach to life, especially cultural life. Theory occupies a place in my life that, for others, is usually reserved for literature, theatre, or art. Just as I barely ever read literary texts, or only those that take the form of an essay (Kertész, Bernhard, and sometimes Hrabal), I find museums dull and art brings me no particular enjoyment. What some people find in novels, poetry, and painting, I find in theory. This inclination often makes me feel out of step with other people’s tastes. Just as I have never understood why the working classes turn to the right or far right rather than the far left when they are disappointed by a moderate left-wing government, I have never understood why so few people are attracted, excited and moved by theory. Why does theory not trigger the same intensity and fervour among the general public as an exhibition or play?

2.

When we speak of ‘taste’, we tend to relate the notion to practices that are associated in the social unconscious with the affects (art, literature, gastronomy, decoration, sex) rather than with activities such as philosophy, which is associated with reason or the mind. But I would like to move away from this artificial divide and consider the question of theory as a matter of taste: what do we like when we like theory? What is at stake when we invest our affects, emotions, and preferences in texts on sociology, philosophy or economics rather than paintings and novels? What effect does theory have on those who read and write it? My aim here is to try to identify what could be described as the fundamental principles of the theoretical libido. Why might someone prefer a book by Bourdieu, Adorno, or Freud and feel a certain thrill as they read them but experience deep boredom when faced with a novel or comic? In my case – and this appears to be quite common – the taste for theory came at the cost of an appreciation of art or culture, just as a taste for art and literature often precludes an enjoyment of theory. Given this, can we identify oppositions between these two preferences, like two opposing psyches or psychologies?

"Universities are not a place for theory. Indeed, they are shaped by extremely powerful anti‑intellectual impulses."

Albert Oehlen, Untitled, 1992–2005 © Photo: Archive Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin, Paris, London / DACS / SPA, Lisbon

3.

By acknowledging the possibility that theory may be viewed as a legitimate focus of libidinal investment, just like art or culture, I would first like to challenge the implicit hierarchy that governs our world. The society in which we live appears to have been deeply affected by what could be described as a symbolic degradation of theoretical activity in comparison with art or literature. I have spoken to numerous painters, artists and filmmakers, who quite openly admitted to never reading philosophy or sociology but looked at me oddly when I said that I rarely visited museums or read novels. As if it were entirely acceptable in our world to overlook theory but not art or literature... As if we were missing out on something if we do not immerse ourselves in the artistic experience but not if we neglect to engage with theory. An artist will always be a little annoyed if a philosopher does not attend an exhibition of their work, yet feel no obligation to read a theoretical volume. Rather than an object of taste and culture, theory is considered as either a task for a specialised professional or a dispensable, secondary taste, a kind of non-essential, parasitic hobby.

It is tempting to explain this distance from theory as the outcome of difficulties in accessing this type of production. Yet those who steer clear of theory tend to prefer works of literature, film and art that are considered esoteric and inaccessible and require a grasp of a series of codes of understanding that are just as elaborate as those involved in any theoretical work. If difficulty is acceptable and a lack of immediate understanding is appreciated when it comes to art, why is theory not treated in the same manner? If difficulty is the only reason for this aversion to theory, what does that mean? Could it point to the existence of a powerful anti-intellectualism in our culture?

4.

If we are to understand the emotions and affective attachments that theory may produce, it is important to understand that what I call theory here has almost nothing in common with the form that it predominantly takes in the university setting. Academic production conveys a distorted image of theoretical work. There is a fundamental difference between the essence of the theoretical activity engaged in by the most eminent authors and the philosophical or sociological discourse produced in the academic disciplines. Foucault rightly raised the possibility that the tendency of universities to render knowledge dull and dreary is a political technology intended to divert people’s attention from knowledge and the freeing effects it might have.

Universities are not a place for theory. Indeed, they are shaped by extremely powerful anti-intellectual impulses. University research is organised into narrow, specialised circles for discussion or publication, which are obsessed with questions of methodology and consistency. Our minds must be constrained, mutilated, and limited in order to fit in. In his Notes on the social sciences and culture, Adorno stresses that universities’ obsession with conformity and control results in a loss of the unique characteristics of the mind: imagination, spontaneity and freedom are all repressed. To illustrate this trend, he cites an academic saying to a student: ‘You’re not here to think, you’re here to do research’. In other words, what I call theory and may also be called thought should be viewed as a practice that takes place outside the framework of academic research, just as modern painting and literature have historically resisted academic supervision.

[...]

Share article