When you make a person disappear, when you annihilate a country, you are murdering a language. These words spoken by Pinar Selek – a Turkish writer, imprisoned and tortured in her country for her pro-Armenian activities, now exiled in France – particularly resonated with me. They reminded me of the words my father used to say when he ran out of threats, before giving me a beating, ‘Shut up, or I’ll cut your tongue out’.

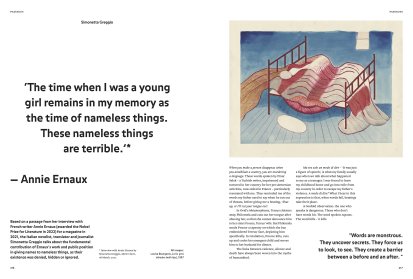

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Tereus cloisters away Philomela and cuts out her tongue after abusing her, so that she cannot denounce him to her sister Procne, Tereus’ wife. But Philomela sends Procne a tapestry on which she has embroidered Tereus’ face, depicting him specifically. In retaliation, Procne kills, cuts up and cooks her youngest child and serves him to her husband for dinner.

The links between violence, silence and death have always been woven into the myths of humankind.

Ma era solo un modo di dire – ‘It was just a figure of speech’, is what my family usually says when we talk about what happened to me as a teenager. I was forced to leave my childhood home and go into exile from my country in order to escape my father’s violence. A modo di dire? What I hear in this expression is that, when words fail, beatings take their place.

A twofold observation: the one who speaks is dangerous. Those who don’t have words hit. The word spoken exposes. The word kills – it kills.

Share article