As the early days of utopianism about the internet seem to be an increasingly distant mirage, there has been no shortage of indictments of the costs and consequences of online life in recent years. After the international success of a small essay about the shrinkage of sleep and the nonstop circus of technocratic life in modernity, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (2013), Jonathan Crary has returned with one of the most uncompromising putdowns of digital capitalism in his book, Scorched Earth: Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capitalist World (2022). ‘If there is to be a liveable and shared future on our planet,’ Crary states in the opening line of this pamphlet, ‘it will be a future offline, uncoupled from the world-destroying systems and operations of 24/7 capitalism.’ This provocative book puts forward the idea that the digital age means both social disintegration and environmental collapse. We have arrived at the terminal stage of global capitalism, Crary argues, as he openly exchanges the nuanced detail of academic writing for the forcefulness of social pamphleteering. ‘The internet complex’, he claims, ‘is the implacable engine of addiction, loneliness, false hopes, cruelty, psychosis, indebtedness, squandered life, the corrosion of memory, and social disintegration’, as ‘the speed and ubiquity of digital networks maximize the incontestable priority of getting, having, coveting, resenting, envying.’ The verdict is loud and clear: ‘The internet has crossed a threshold of irreparability and toxicity’, as we now face ‘a world operating without pause, without the possibility of renewal or recovery, choking on its heat and waste.’

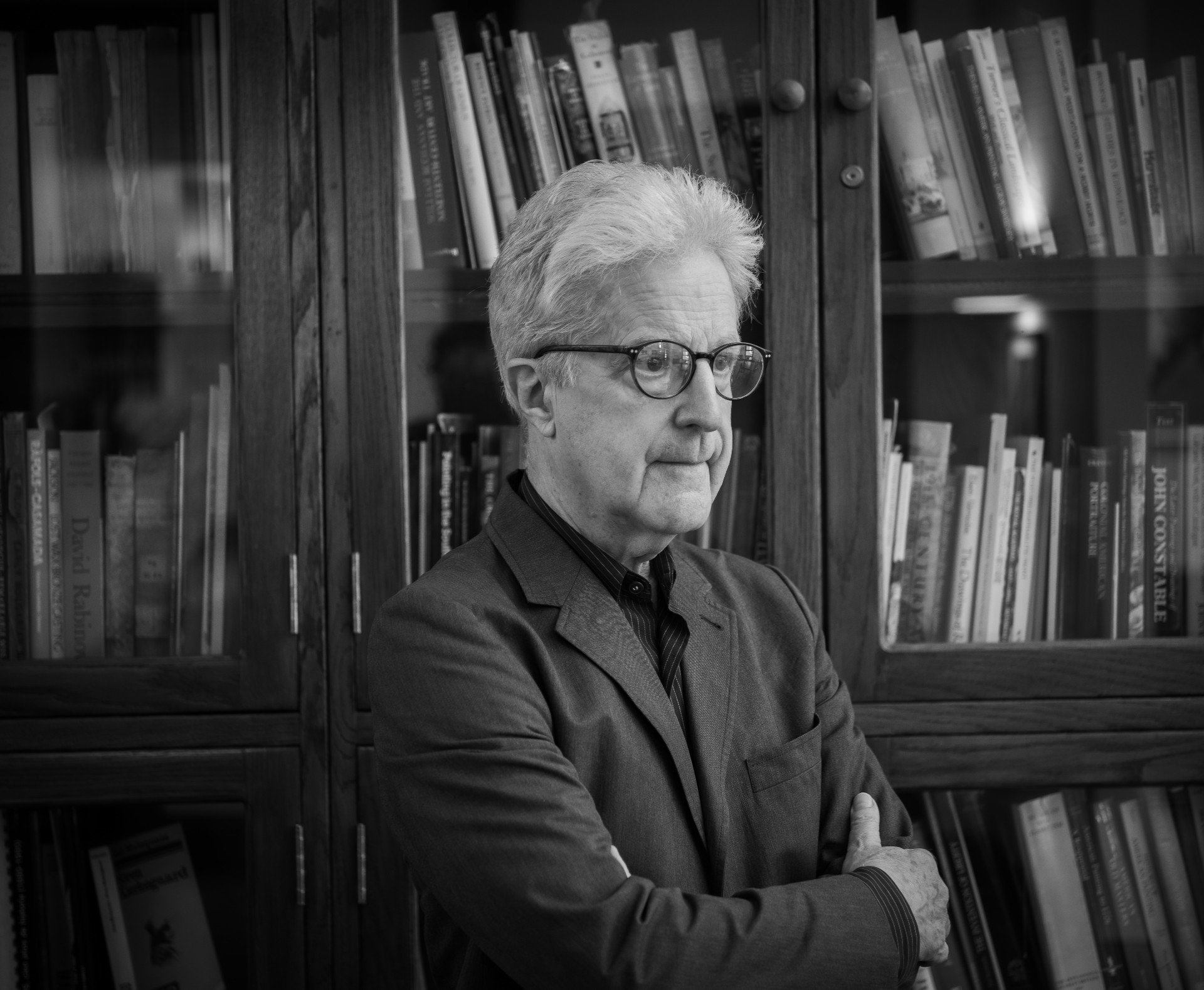

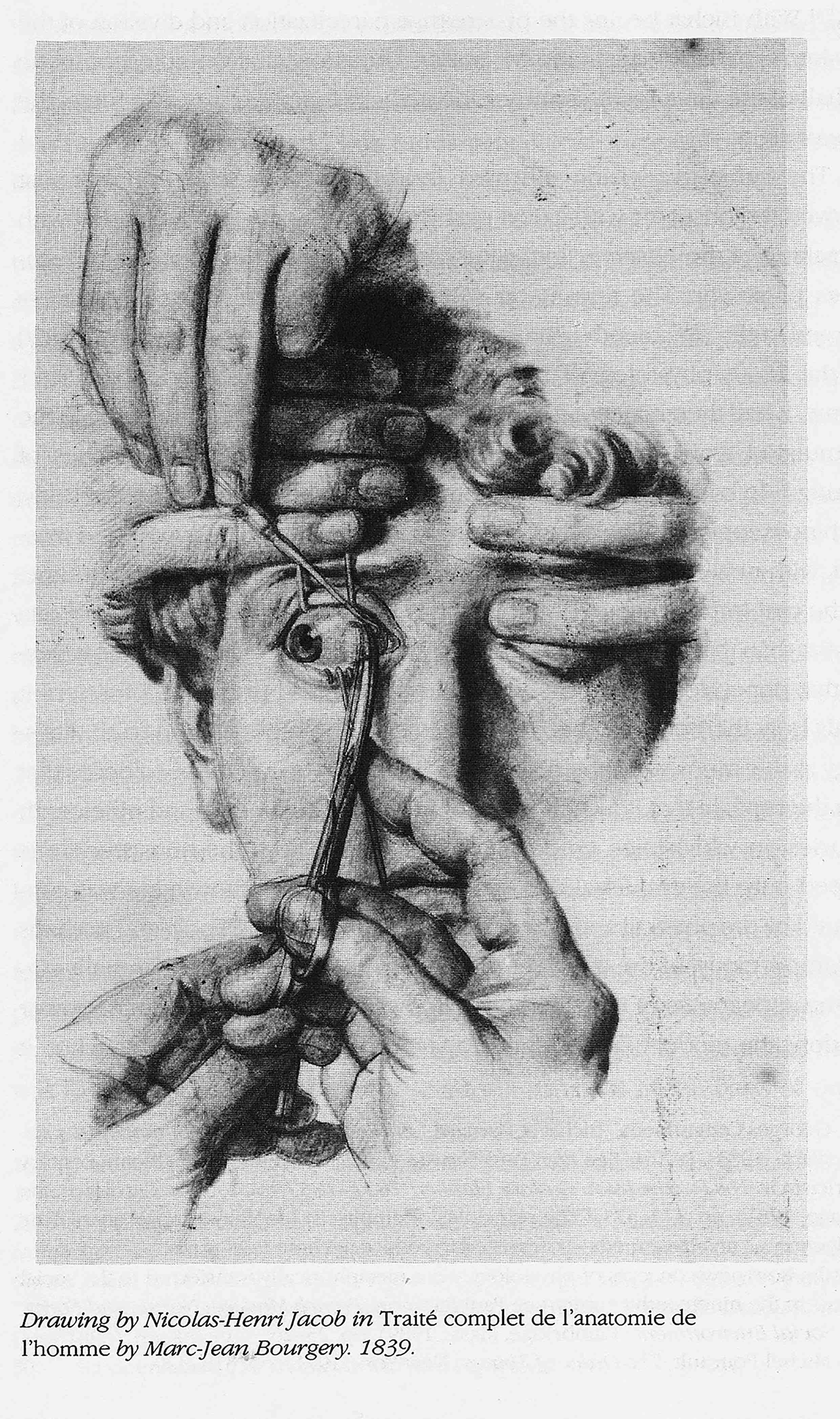

Jonathan Crary is the Meyer Schapiro Professor of Modern Art and Theory at Columbia University in New York, and has also been a visiting professor at Princeton and Harvard University. He was a founding editor (and continues to be co-editor) of Zone Books, an independent nonprofit publisher. An acclaimed political theorist, critical thinker and art historian, Jonathan Crary is the author of indispensable studies about the formation of visual culture in the 19th and early 20th century, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the 19th Century (1990), and Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle and Modern Culture (2000).

Share article