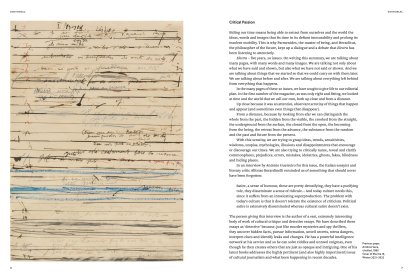

The person giving this interview is the author of a vast, extremely interesting body of work of cultural critique and detective essays. We have described these essays as ‘detective’ because, just like murder mysteries and spy thrillers, they uncover hidden facts, pursue information, unveil secrets, stress dangers, interpret clues and identify leaks and changes. He has a powerful intelligence network at his service and so he can solve riddles and unravel enigmas, even though he then creates others that are just as opaque and intriguing. One of his latest books addresses the highly pertinent (and also highly impertinent) issue of cultural journalism and what been happening in recent decades.

In this interview with Electra, his ideas follow on from one another as he proposes hypotheses of understanding, ways of questioning and forms of (satirical and self-mocking) cross-examination. This is what we refer to as ‘critical thinking’, calling upon centuries and centuries of sedimentation of what we call culture for the act in which this thinking can be put to the test.

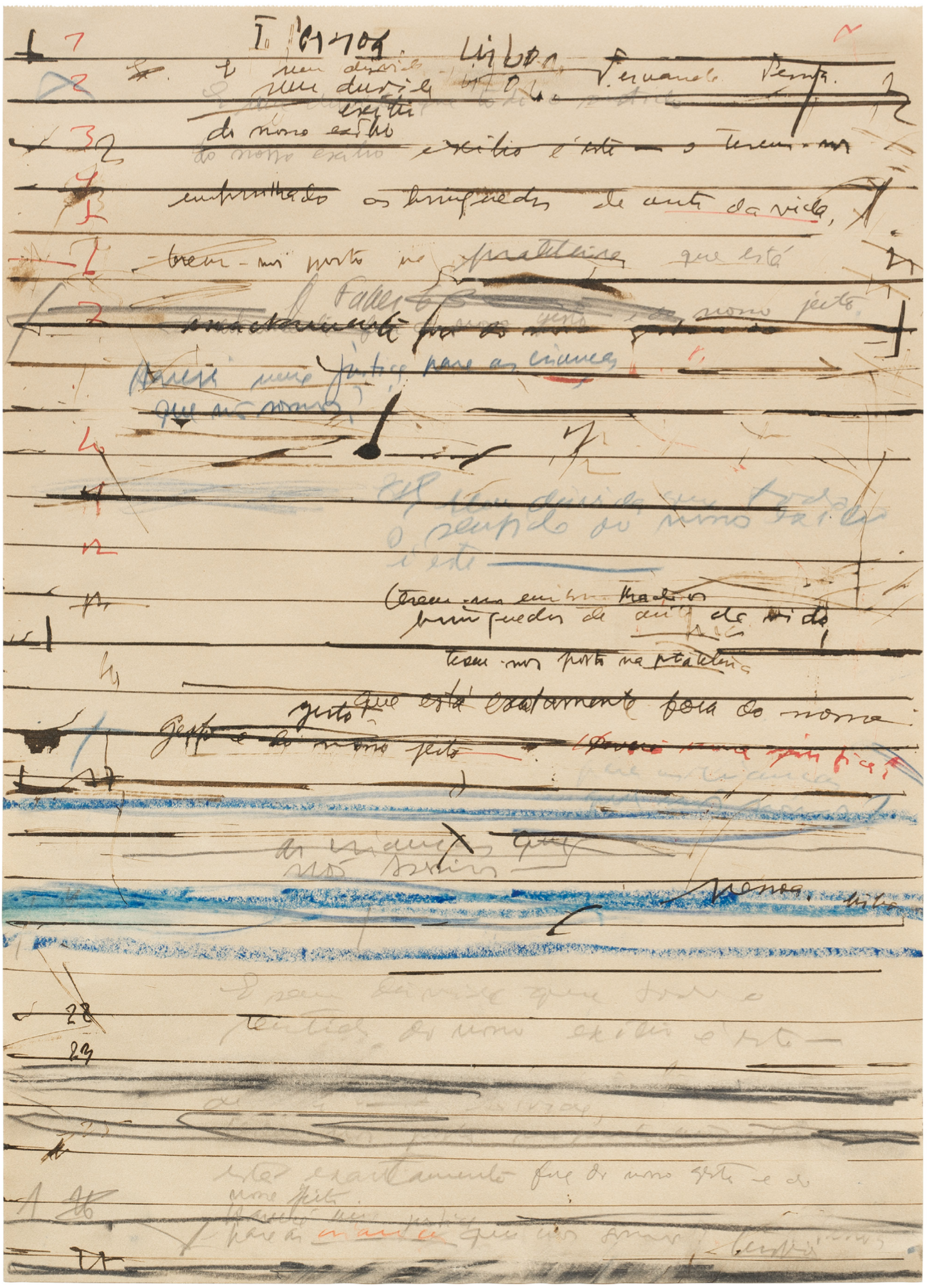

A close friend of Hans Magnus Enzensberger – the great German writer who died recently and about whom he wrote for Electra 18 – Berardinelli is more than a master of reading, as George Steiner liked to say of himself; he is rather, as Fernando Pessoa would say, ‘a disruptor of souls’.

If in this Editorial we are quoting from an interview that you can read further on, it is because it both affirms and confirms a great critical gap in the times in which we live and makes sense of the need to mitigate it, something that our editorial programme identifies with and raises awareness of.

In all the issues of Electra and in line with each subject matter, we have sought to open the way for a critical spirit to be applied and developed through a constant, deliberate openness to the verbal and visual forms in which this indefatigable spirit can dig deep.

To be genuine, profound and meaningful, criticism of politics, culture and society requires courageous lucidity and transgression; it requires risk and intellectual daring that hardly anyone seems interested in or capable of showing. It requires new, different, imaginative, unorthodox ways of thinking.

With well-aimed perversity, the power system in our times has managed to strip the authority away from all forms that threaten or detract from it or that create real, trustworthy, productive and therefore menacing alternatives to its rule. It has absorbed them, accommodated them, tamed them, falsified them, appropriated them, commoditised them and made them tools that prolong and corroborate the power that they seem to dispute.

With few exceptions, political criticism (so-called ‘commentary’ or ‘opinion’) has become a futile media spectacle; literary and artistic criticism (with inevitable star ratings) is editorial marketing and career-hungry mediocrity; social criticism (with its arrogant, two-faced academisation) stimulates inequality and conformism; economic criticism (with its compromising dependence) fosters continued single thought; and sports criticism (with its fraudulent montage) puts on an endless football reality show that sponsors unconfessed interests and unacceptable conveniences. Indeed, in all the circumstances in which we have just used the word ‘criticism’, we could and should prefix it with ‘pseudo’.

It is as if the current ‘order of things’, with its controlling device and the asphyxiating, totalitarian ideology emanating from it, had no exterior or, in the name of an artificial, bogus or imposed realism, did not accept the existence of any alternatives threatening its ‘eternity’.

Wanting to have genuine critical thinking in a world-setting like ours is almost like trying to make yourself heard in the midst of a raucous, massifying uproar that has no truck with any dissonance or disagreement. It is like wanting to wear something different when everyone else is dressed in the same uniform. But it is this ethical and cultural purpose that must be kept up.

In the awareness of this purpose, it is to original, unique voices of authors that Electra endeavours to listen, attract, capture, record and broadcast. These are the voices that can convey the sounds and signs of a thinking that refuses to be shouted down, tamed or besieged.

As they are the voices (or images) of critical thinking, the first requirement that they have to impose upon themselves is that of looking at the unstable, restless physiognomy of the world in which we live, with its radical changes, metamorphoses, transformations, ruptures and drifts. It is keeping up to date with the new forms of invention, creation, reproducibility and proliferation. It is not ignoring seduction, enticement, fraud, sham or manipulation methods. It is not underrating means of control, homogenisation, surveillance, blocking, harassment, confrontation and usurpation. This is also what Alfonso Berardinelli says in this interview. He is both detached and vigilant, personal and impersonal, local and universal, melancholic and combative.

Octavio Paz, whom Berardinelli also mentions, once warned:

Share article