On 25 August 1979, Roland Barthes wrote: “I return with relief to Mémoires d’outre-tombe, the real book. The thought always comes to me: What if the modernists got it wrong? If they had no talent?”1

Barthes wrote these words, but he never published them. Not much more than six months later, on 26 March 1980, he died without having had time do anything with them. What would he have done? This is something we will shortly try to understand. Nevertheless, these words of his did reach us: they appeared in a posthumous collection put together by his friend and editor, François Wahl (1925-2014), published under the title Incidents in 1987, seven years after his death.

It is a strange book. It includes two very brief texts, one about “La lumière du Sud-Ouest” and another about a nightclub, “Au Palace ce soir”. Barthes had given the first to the communist daily paper L’Humanité, the second to a high-quality fashion magazine, Vogue Homme. Added to these were a series of unpublished and very personal fragments about Morocco, “Incidents”, which gave the collection its title. Everything about this curious ensemble is odd, from the juxtaposition of the two intimate texts (“Soirées de Paris” and the piece about Morocco) with two texts that are completely “extimate” (the one on the South-West of France and the one on the Palace nightclub), to the publications where the two articles first appeared: L’Humanité, the organ of the proletariat, and Vogue Homme, a magazine representing capitalism and hedonistic consumption. For my part, I see the first signs of postmodernism in this improbable and unexpected medley: the corrosion of the great ideological, social, economic and cultural certainties that began to bite at the beginning of the 1980s, the end of modernism.

Barthes’ readership was shocked. It appeared that François Wahl had used these anodyne articles (the two that had appeared in L’Humanité and Vogue Homme) to mask a double betrayal of his friend Barthes. The first betrayal touched on his lifestyle: both “Soirées de Paris” and the piece about Morocco contained revelations, sometimes very crude, about Barthes’ gay sexuality – a sort of outing, or rather an involuntary comingout, since Barthes had never spoken, at least openly, about what today would be called his “sexual orientation”. The second betrayal might be regarded as equally serious: there are several passages in “Soirées de Paris” where Barthes seemed to denounce “modernism” and the “modernists”, the whole avant-garde movement with which he was associated as one of its leaders, commentators and associates. This was the more vicious betrayal, not only because Barthes was attacking the modernists, who towards the end of the century were already in difficulties, but also because his attitude to modernism could have been seen as exhibiting the sort of hypocrisy that Molière’s Tartuffe was famed for.

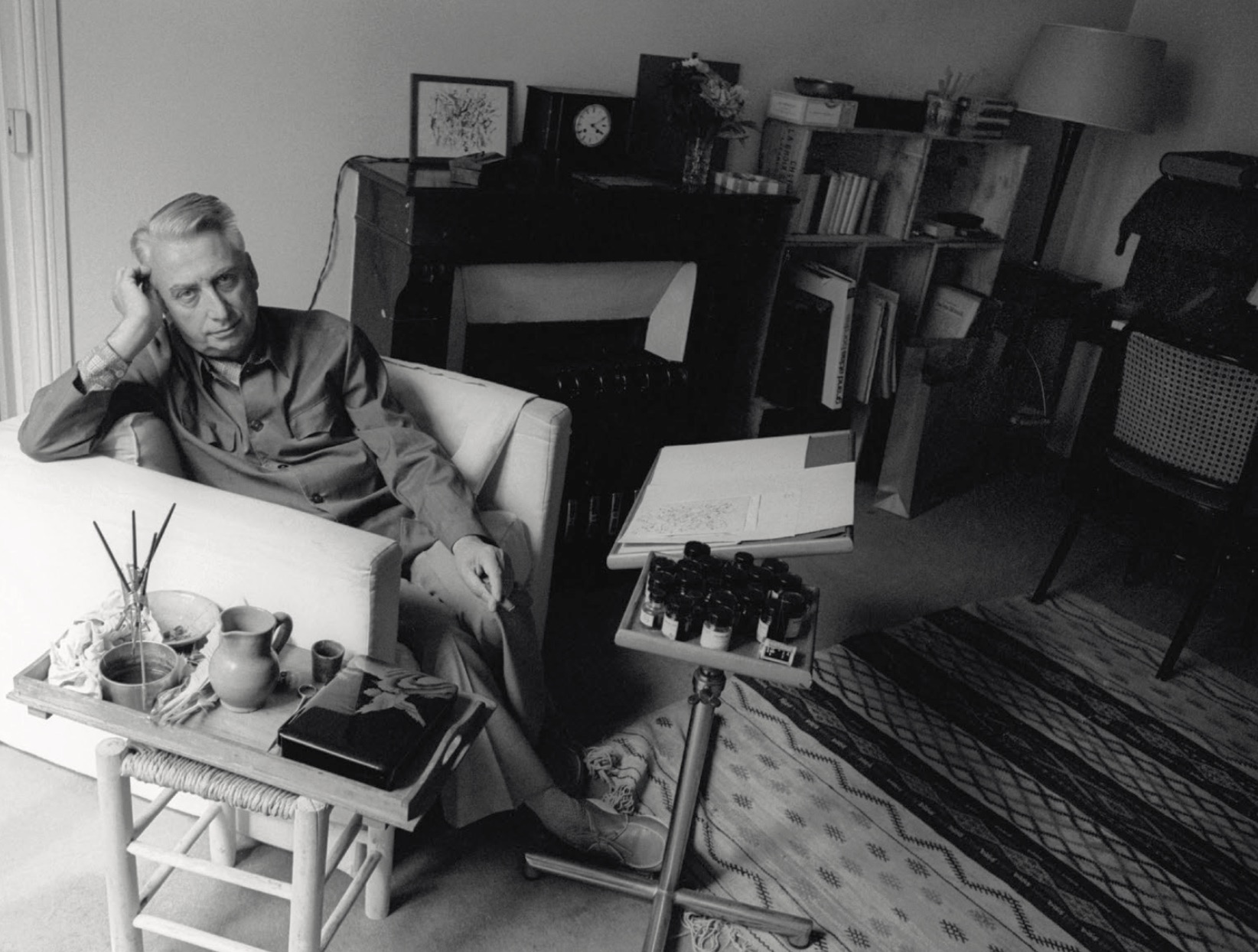

Barthes’ harsh question about the modernists – “What if they had no talent?” – came at the end of an evening (all the pages except the last in this “diary” describe evenings) that has a special meaning for me because I was there when it began: “A simple meal, at the Flore, with Éric M., where we had frankfurters, soft-boiled eggs and a glass of Bordeaux.”2 Barthes goes on to describe the evening we spent together at the Café de Flore, an emblem of intellectual life, where Sartre is supposed to have written L’Être et le Néant. Barthes went there often, but today it has become a rather tawdry café, packed with tourists. The passage contains a nice mise en abyme: after relating that we had talked about diaries, Barthes says that the piece he has just written, “Délibération”, which is specifically about the diary, or journal intime, will be dedicated to me – and all this is recounted in “Soirées de Paris”, which is itself a diary.

On his return home, Barthes read passages out of a few different books, as he did every night before going to sleep: some “modernist” books to start with, on this occasion, and afterwards Mémoires d’outre-tombe, “the real book”.

Perhaps we ought to take a look at the two books he opened and then closed again before picking up the one that he kept returning to, the Chateaubriand. The first is referred to by the name of the author (Navarre), the second only by the title, M/S. Were these modernists in the historical or aesthetic sense? Not at all. The first was Yves Navarre (1940‑1994), an author whose writing was utterly traditional and whose sole act of daring was to write gay novels. The one that Barthes was reading was Le Temps voulu, a fairly formulaic love story between a university professor and a very young man. The other book, M/S, whose author is not named, is more mysterious. These days it is extremely difficult, in fact practically impossible, to find any information at all about this book on the internet. The author’s name cannot be traced. It is Christian Pierrejouan, and his novel is about an extreme sadomasochistic homosexual relationship. Barthes mentions it once more in his entry for 5 September 1979 – again omitting the author’s name – in a passage relating to François Wahl, the book’s enthusiastic editor (to the point where he was rumoured to have written it himself, which was not the case). But again, despite the extreme nature of the sexual practices that it describes, this is in no respects a modern book, a “text”, a piece of textualizing modernist writing. I remember that this book, placed in full view on Barthes’ bedside table, had been covered in very thick black paper: Barthes did not want his cleaning lady to read the plot summary on the back cover.

Share article