The attitude that consists of always naming the stupid and defining stupidity as something other that one must expel often falls into a classic form of stupidity, the ostentatious exhibition of a presumption of intelligence. That risk was successfully identified by Robert Musil in a lecture delivered in Vienna in 1937. It became a vital reference for those who study this persistent theme, which must be faced with a sense of urgency. Starting with the title, Musil came straight to the point, treating it as the subject matter of a brief treatise: On Stupidity (Über die Dummheit). To reduce the risk of falling into the traps that stupidity presents against presumed intelligence, Musil moved cautiously, introducing the metadiscourse and suggesting modesty as “the most important weapon against stupidity”. And, with humour and the strong analytical sense that turn-of-the-century Viennese culture had imparted to him, he explained to his audience that every intelligence has a corresponding stupidity, thus granting it the same universality that Descartes had given to common sense. In a page of The Man Without Qualities, we find the most eloquent and irony-filled formula to prevail over the dialectics between stupidity and intelligence, the idea that there is an integral relationship between the two: “And after all, if stupidity did not, when seen from within, look so exactly like talent as to be mistaken for it, and if it could not, when seen from the outside, appear as progress, genius, hope, and improvement, doubtless no one would want to be stupid, and there would be no stupidity. Or fighting it would at least be easy.” What Musil refrains from is answering the question that he asks in the beginning with a definition: “Just what is stupidity?” We are left to assume that it is not possible to define the matter.

Nonetheless, it is a perennial topic that has always aroused the interest of philosophers and writers. With greater or lesser success, there are some who have embarked on a phenomenology of stupidity. And those who, reflecting on its genesis, described it as a “scar”: as Adorno and Horkheimer did in the last section of Dialectic of Enlightenment. The difficulty in fighting it stems precisely from its character of a hard protuberance, of something robust. Engaging in open warfare with stupidity has almost always been useless and often a bit stupid (we have tried to veer away from the idea of a declaration of war in the conception of this Electra issue).

Flaubert was perhaps the first to grasp this trait, by defining stupidity as “something unshakable; nothing attacks it without breaking itself against it; it has the nature of granite, hard and resistant”. He knew what he was talking about. The stupidity that he was obsessed with was the kind expressed by the French word bêtise, which evokes bestiality, the descent into an animal-like state. Stupidity, bêtise, idiocy, imbecility: here is a constellation of terms that are difficult to tell apart and form a problematic universe. We take a very particular interest in Flaubert because, for him, stupidity was not a theoretical question (he never intended to produce a theory of stupidity), but a historical one. His idiophobia was expressed this vehemently: “Against the bêtise of my time, I feel floods of hatred that choke me. Shit rises to my mouth as in the case of a strangulated hernia.” And, in this way, he initiated an analysis of epochal, social, political and collective stupidity, which is not the same as individual stupidity, associated in our minds with a lack of intelligence and measurable on an intensity scale. Since Flaubert, the idea that there is a modern form of stupidity has taken shape, related to the social form of the “bourgeois” and to mass culture. Hence the idea that each age concocts its particular manifestations of stupidity, as a “language” that belongs to it. Flaubert tried to capture the stupidity of his age by collecting its “clichés”, in a Dictionnaire des idées reçues that was, perhaps, to be the second part of his unfinished work Bouvard and Pécuchet. These are the names of the two idiots that take the idea of an encyclopaedia of all knowledge ad absurdum, representing it as a farce. Devoted to a succession of failed tasks, these stupid servants of science succumb to the utmost discrepancy between theory and practice.

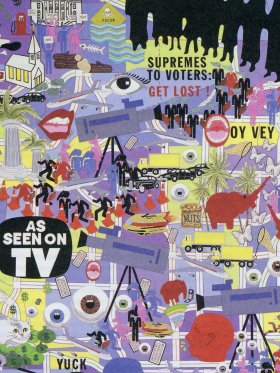

The sense in which Flaubert uses the word cliché is not that of classical rhetoric: it is the repetition of a formula that appears automatically, crystallized and mandatory by the abandonment of all thought and criticism. Cliché is everything that extracts, from the hyperbolic principle of identity, the strength to continue ever more vigorously: “It is what it is,” “War is war,” and forget about it, because “There are no free lunches.” The Flaubertian negative passion was revived by Barthes, in his critical analysis of the stereotype, “this nauseating impossibility of dying” and, more indirectly, in his “mythologies”, which were also, in their own way, an inventory of “idées reçues”. But this time, in the age of mass media and consumer society, it was necessary to analyse the new mechanisms that fabricated and distributed them, hiding them behind the screen of ideology. That is why the critique of ideology, with its demystifying goal, was the huge task undertaken by the generation that reached their peak in the 1960s and 1970s, who invested a great deal of their intellectual energy in “theory” and “theoretical work”, as it was called at the time.

Is there a present-day boom in this social, collective and political stupidity? This perception is probably as illusory as the idea taken up by each generation that we are at the edge of the abyss. But the configurations of the present universe of communication simultaneously enhance and slow down this age’s stupidity. They are a pharmakon, both the poison and the medicine. It is true that the tools for exercising critical reason have lost their force and the critique of ideology now seems a thing of the past. But it must be noticed that this critical reason has often become the opposite of itself, as Adorno and Horkheimer have clearly shown.

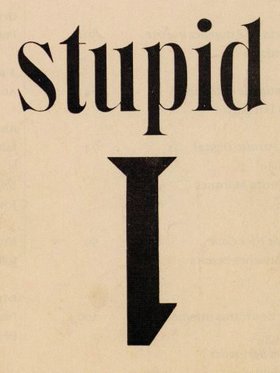

The social impact of television and, more recently, new communication technologies is enormous. But we should refrain from thinking that the media mechanisms that multiply and amplify stupidity belong exclusively to our own age or that there was ever a time when everything was virtuously and immaculately intelligent. Karl Kraus’ fight against the journalism of his time was a fight against venality, ignorance and stupidity. Flaubert said that stupidity consisted of wanting to reach conclusions (and Barthes continued in the same vein, when he wrote that “stupidity is the euphoria of the place”, i.e. that indiscrete glee arising from self-complacency and satisfaction with ourselves). Well, drawing conclusions is what is practised most in a regime of instantaneous communication that promotes opinion.

If stupidity, as we understand it here, drawing on a Flaubertian matrix, is a typically modern phenomenon, it is also true that it does not present exactly the same characteristics today. Flaubert intended to isolate it and identify its occurrences. On the contrary, it is no longer possible to isolate present-day stupidity, as it is disseminated everywhere. It is identified with society as a whole, with the rules of the social and political game, following and even creating the flow of culture. For instance, in the forms of diffusion and legitimization, can anyone distinguish between entertaining literature and literature that assumes a strong responsibility towards the tradition from which it emerges (in a dialogue with literary history) and its own time?

Share article