There are generally three types of Airbnb properties. Firstly there are the “real homes”, occupied by long-term residents, and only rented out on occasion. Then, there are the investment properties, occupied by their owners only occasionally, and rented out frequently in order to pay off a mortgage. And the third category – the kind that does not concern us here – consists of properties that are just hostels or hotels in disguise.

The “real homes” are always littered with what Philip K. Dick called “kipple” – those personal affects which, together, form the meaningless dross and detritus that accumulates over time. Ageing family photographs, chipped fridge magnets, mismatching cutlery, vast quantities of used take-away chopsticks and plastic bags. Furniture, marked by the battle scars of past moves and decades of use, huddles together awkwardly in a manner that suggests the residents no longer really see their forms. Clutter lurks in every appropriate corner, conveying a certain pragmatism: the home may or may not be attractive, but the umbrellas are just where you think they might be. Like learning the tastes of a new lover, these places always come replete with baggage, rules and idiosyncrasies. “If the hot water pipes start to bang,” a Post-It note suggests, “just turn the tap down a bit.”

The second category, the “investment properties”, are always slightly uncanny – they appear as if a nervous and alienated individual has transposed a Starbucks lounge setting into a stage-set apartment. Furniture, where it is not Ikea, is overblown. The out-of-scale blue velvet winged armchairs overcompensate for the lack of kipple, but only highlight further the absence of life. These interiors are often “quirky,” employing decorative and architectural one-liners peddled by home-renovation television programmes: sober Louis XV chairs with an ironic twist of pink faux Leopard; flaking gilded picture frames hung unfilled on the wall and packed with motivational (almost mimetic) messages clipped from magazines; the functionless chalkboard paint feature wall, at its edge a few love hearts, a non-specific but friendly message of welcome (“hi! xoxo”) and the wifi password. Inasmuch as they strive to appear casual and homely, yet professional and modern, these are already-always finished interiors. No new objects can be added to them, nor taken away.

The investment property, with some aloofness, converges on the aesthetics of the ‘real home’. Simultaneously, the real home directly approaches the investment property. The standardisation policies of Airbnb dictate how, and from what angles, rooms can be photographed, and even suggest certain objects or colour schemes that might enhance the “look” of a property. The aim of this is to provide a more legible comparison of images by the website or app user. In other words, the blurring of the lines between the appearance of the home and that of the investment property is designed to render culturally and geographically diverse properties exchangeable – in every way homogenous and homotopic.

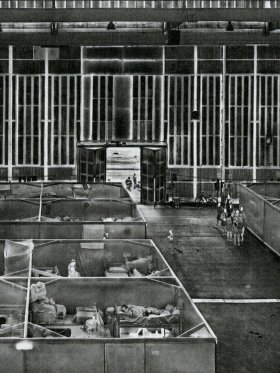

The confluence of these two categories might be called the “investment home,” and presents rather novel, and ambiguous, architectural conditions. Foremost amongst these is the parcelisation of personal space. In the investment home it is common to see specific markers outlining the borders of the private: the bedroom wardrobe is empty, like in a hotel, awaiting the clothes we will never arrange in it. But the bottom drawer will be marked by a red sticker, or a note, asking and trusting the temporary occupant not to disturb this last private space. This atomisation of privacy is only the latest reduction in a process of domestic commodification that began with the advent of mass home ownership after the 1970s. Yet it would be wrong to think that it is specifically the technology of Airbnb that is solely responsible for the disappearance of soul in the home. Rather, it is but one easily seized upon model amongst a myriad of image-based informatic exchange technologies – all of which aim to render every detail of our lives and personalities comparable, and therefore fungible.

At least amongst radical liberals, the home has always stood as the pinnacle of personal freedom. On the street, free speech and common courtesy are respected, while lethal force upholds the sanctity of private property. But the Airbnb interior, with its partitioned privacy, is a private home made accessible to the public for a fee. This directly exposes the relationship between personal taste, socioeconomic status and profitability, explaining why the generic home is so ideologically uncomfortable. It is at once both public and private, but neither public nor private. This ambiguous condition produces what I term quantum space.

In fact, the image- or icon-based informatic technologies we increasingly use to mediate our perception of reality extend this condition of indeterminacy far beyond Airbnb. The video call that brings friends in a foreign café directly into the space of the bedroom performs an abstraction of public-privacy. Equally, the predictable frame of reference embedded in the multiplicity of the “selfie” transposes the tourist in a strange land into a familiar space: into a state of private-publicness. The impossibility of being completely alone (there is always the threat of the text alert’s call to arms) is mirrored only by the impossibility of truly being part of the group (we literally cannot hear each other over the sound of our personalised music playlists). At the scale of the city, the progressive privatisation of public space is complemented by the extension of government surveillance (whose totalitarian extents were chillingly revealed by Edward Snowden) into the privacy of our homes, hard drives, histories and heads.

[...]

Share article