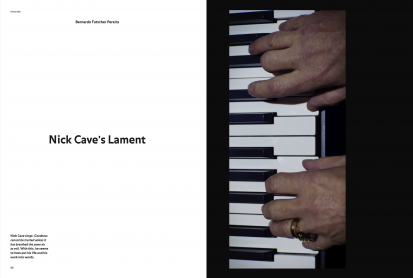

Goodness cannot be trusted unless it has breathed the same air as evil.

Nick Cave, 1996

Nick Cave belongs to a generation for whom rock and roll was still enveloped in a mythical aura. Its practitioners were demigods, not mere celebrities. Although he has not yet ascended to the Olympus where pop superstars like Elvis Presley, John Lennon, Bob Marley or David Bowie are enthroned, Nick Cave is, by profession, a rock star, with all the megalomania, exhibitionism, transgression, and excess that it implies. His path, followed by thousands of fans, is widely documented in the score of albums he recorded throughout his career, in the lyrics of his songs, fully transcribed at azlyrics.com, and in dozens of interviews, documentaries, films and concerts available on YouTube. However, what makes him unique in the universe of pop music is his literary talent, which sets him along the glorious path of the sacred monsters, Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen.

I saw him for the first time in the second half of the 80s, at the Sports Pavilion in Parque Eduardo VII. I believe this was his first performance in Portugal, at the time already with the Bad Seeds, who became his band after the break-up of the Birthday Party. The histrionic violence of the concert, the almost unbearable noise, aggravated by the shrill feedback of the electric guitar, did full justice to their tenuous but growing reputation as a post-punk neo-gothic band. Nick Cave, with a uniform he would never abandon – dark suit and open shirt, collar sticking out of the jacket, like an outlawed Travolta – wandered, possessed, across the stage, threw himself on the floor, and yelled into the microphone, against the backdrop of a furious barrage of sound.

Live concerts, their celebration, rapture, and collective catharsis have always been the high point for rock lovers. I went to see Nick Cave, driven by curiosity, and did not immediately become a fan, as had happened for example with Talking Heads – a case of love at first sight. I remember Nick Cave’s concert as a complete attack on the senses. However, something threatening, haunted, disturbing and truly devilish stayed with me and gave rise to the long relationship I have since maintained with his music and poetry, a relationship bordering at times on obsession.

Nick Cave is a poet, a lyrical and satirical poet, a poet of dreams and prayers, and a storyteller: stories of violence and crime tinged with dark humour, stories of betrayal and death, stories of poor devils lost in the tribulations of life, stories of failed marriages and sex-hungry men, and, above all, melancholic love stories. He is also a writer of prose, the author of two novels, And the Ass Saw the Angel and The Death of Bunny Munro, the latter being the frantic saga of a travelling salesman addicted to sex. I bought it on a collector’s impulse and ended up reading it in one go. He has produced two films that document his creative process, 20,000 Days on Earth and One More Time with Feeling. Nick Cave’s imagination is filled with violence, perversion, pain, remorse, and guilt, feelings redeemed in his songs through humour and art. I sometimes wondered whether Nick Cave did not obscurely channel the collective unconscious of Australia, which before becoming a cool paradise for surfing, Shiraz, and fusion cuisine, was a prison and a place of exile, colonised with the lash by soldiers and criminals. However, I decided he does not; I rejected that blunt hypothesis. His inspiration runs deeper than that. It springs directly from a spiritual quest, on the precarious border between good and evil.

My second contact with Nick Cave was through his album The Good Son, released in 1990. I bought it because of the cover: the unexpected photograph of Cave at the piano, surrounded by four angelical blonde girls in tutus, perverse muses blowing him inspiration. In my memory none of the primal violence of his first concert prepared me for the majestic, epic ballads that open the album: Foi na Cruz, The Good Son, The Weeping Song, and the amazing Lament, one of the first examples of a love song in his discography, a genre Cave would later practise with virtuosity. (“I’ll miss your urchin smile, your orphan tears/ Your shining prize, your tiny cries/ Your little fears/ I’ll miss your fairground hair/ Your seaside eyes/ Your vampire tooth, your little truth/ And your tiny lies.”)

[...]

*Translated by Moira Difelice

Share article