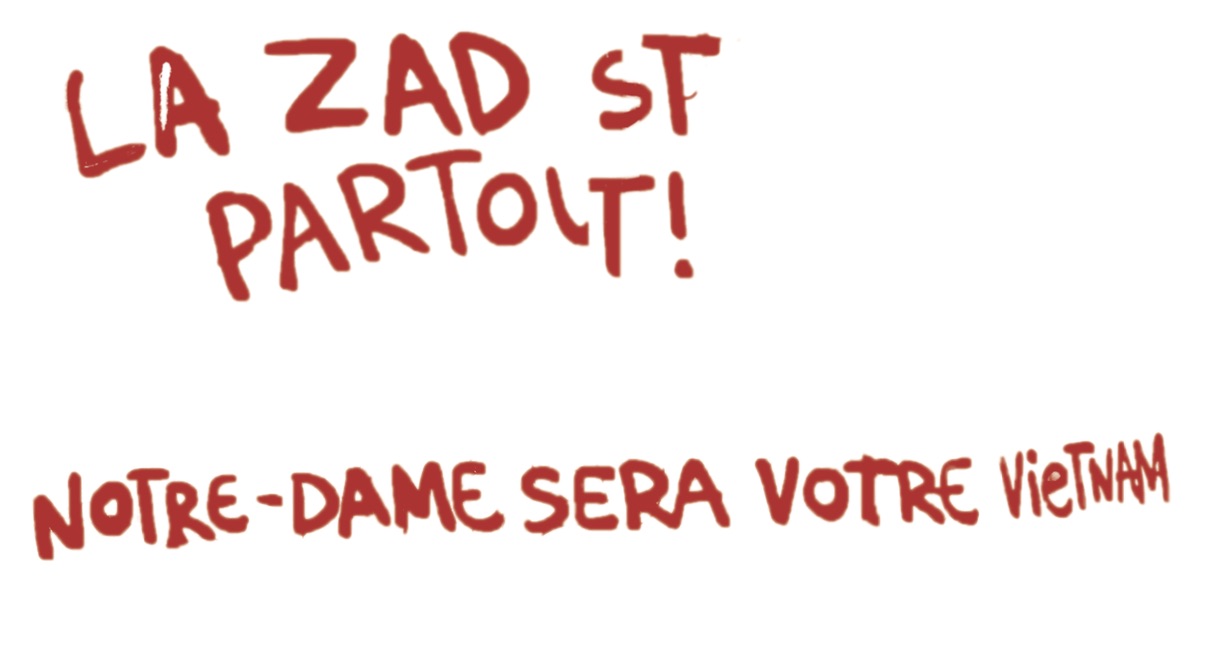

Sanrizuka and the Larzac share with the zad a number of practices and characteristics above and beyond their use of occupation as a form of direct action, and above and beyond their direct involvement with the means of subsistence. One such practice is the act of defending per se, embodied in the ancient figure of the “paysan” whose name, etymologically, means “someone who defends a territory.” The idea of defense is, of course, prominent as well in a word that only entered the French dictionary two years ago, namely zad, or “zone à défendre.” Japanese farmers in Sanrizuka, taking a tip from North Vietnamese peasants in their war with the United States, went so far as to bury themselves in underground tunnels and trenches to prevent the entry of large-scale construction machinery into the zone. At a moment when the state-led modernization effort had made accelerated industrialization the sole national value in Japan, farmers countered with their conviction that the airport would destroy values essential to life itself. In Notre-Dame-des-Landes, farmers who refused to sell their land were joined by nearby townspeople and a new group after 2008: squatters and soon-to-be occupiers. With the arrival of the first squatters, the ZAD (zone d’aménagement différé) became a zad (zone à défendre)—the acronym had been given a new combative meaning by the opponents to the project, the administrative perimeter of the zone now designated a set of porous battle lines, and the act of defending had replaced the action we are much more frequently called upon to do these days, namely, resist. The history of these movements shows us that defending is more generative of solidarity than resisting. Resistance means that the battle, if there ever was one, has already been lost and we can only try helplessly to resist the overwhelming power the other side now wields. Defending, on the other hand, means that there is already something on our side that we possess, that we value, that we cherish, and that is thereby worth fighting for. African-Americans in Oakland and Chicago in the 1960s knew this well when the Black Panther Party of Self-Defense designated black neighborhoods and blackness itself as of value and worth defending. What makes a designation of this kind interesting and powerful is that it enacts a kind of transvaluation of values: something is being given value according to a measurement that is different from market-value or the state’s list of imperatives, or existing social hierarchies. In the case of the Larzac, a spokesman for the then Minister of Defense, Michel Debré characterized the zone chosen for army camp expansion as a desolate limestone plateau, populated, in his words, by “a few peasants, not many, who vaguely raise a few sheep, and who are still more or less living in the Middle Ages.”3 As for the land designated for the airport at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, it was regularly described in initial state documents as “almost a desert.”

So the gesture of defense begins frequently by proclaiming value, especially a kind of excessive value, where it hadn’t been thought to exist before, in a manner I’ve discussed elsewhere that the Parisian Communards of 1871 called “communal luxury.”4 By designating something that had no value before in the existing hierarchy of value to be of value and worth defending one is not calling for equivalence or justice within an existing system like the market (as in the demand for fairer distribution). One is not calling for one’s fair share in the existing division of the pie. Communal luxury means that everyone has a right not just to his or her share, but to his or her share of the best. The designation calls into question the very ways in which prosperity is measured, what it is that a society recognizes and appreciates, what it considers wealth.

And what it is that is being defended, of course, changes over time. To return to the Larzac, Sanrizuka, and the zad at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, these are what the Maoists used to call “protracted wars”—struggles that keep changing while enduring and whose strikingly long duration has everything to do with the non-negotiability of the issue. An airport is either built or it is not. Farmland is either farmland or it has become something else: housing developments, say, or an army training ground. But where once what was being defended might have been an unpolluted environment or farmland or even a way of life, what is defended as the struggle deepens comes to include all the new social links, solidarities, affective ties, and new physical relations to the territory and other lived entanglements that the struggle produced.And what it is that is being defended, of course, changes over time. To return to the Larzac, Sanrizuka, and the zad at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, these are what the Maoists used to call “protracted wars”—struggles that keep changing while enduring and whose strikingly long duration has everything to do with the non-negotiability of the issue. An airport is either built or it is not. Farmland is either farmland or it has become something else: housing developments, say, or an army training ground. But where once what was being defended might have been an unpolluted environment or farmland or even a way of life, what is defended as the struggle deepens comes to include all the new social links, solidarities, affective ties, and new physical relations to the territory and other lived entanglements that the struggle produced.And what it is that is being defended, of course, changes over time. To return to the Larzac, Sanrizuka, and the zad at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, these are what the Maoists used to call “protracted wars”—struggles that keep changing while enduring and whose strikingly long duration has everything to do with the non-negotiability of the issue. An airport is either built or it is not. Farmland is either farmland or it has become something else: housing developments, say, or an army training ground. But where once what was being defended might have been an unpolluted environment or farmland or even a way of life, what is defended as the struggle deepens comes to include all the new social links, solidarities, affective ties, and new physical relations to the territory and other lived entanglements that the struggle produced.And what it is that is being defended, of course, changes over time. To return to the Larzac, Sanrizuka, and the zad at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, these are what the Maoists used to call “protracted wars”—struggles that keep changing while enduring and whose strikingly long duration has everything to do with the non-negotiability of the issue. An airport is either built or it is not. Farmland is either farmland or it has become something else: housing developments, say, or an army training ground. But where once what was being defended might have been an unpolluted environment or farmland or even a way of life, what is defended as the struggle deepens comes to include all the new social links, solidarities, affective ties, and new physical relations to the territory and other lived entanglements that the struggle produced.

And it is those solidarities, the soldering together of what are often the most diverse of groups and individuals, that characterize movements like these. In Sanrizuka, an improbable coalition came into being through the encounter between farmers, who began by defending their way of life but learned in the process the true violence of which the state was capable, and radical urban students and workers who had never before given a thought to where and how the food they ate was produced. The force of the Larzac movement lay in the diversity of people and the disparate ideologies it brought together: anti-military activists and pacifists (conscientious objectors), regional Occitan separatists, supporters of non-violence, revolutionaries aiming to overthrow the bourgeois state, anti-capitalists, anarchists and other gauchistes, as well as ecologists. But while the Larzac movement indeed gathered together a diversity of social groups and political tendencies under its umbrella, at no time was the fundamental leadership of the farmer families who had spearheaded the movement ever in question. Sympathizers who supported the farmers politically and financially, usually from afar but sporadically in vast demonstrations of hundreds of thousands of people who had traveled to the plateau, were supporting the visceral attachment of the farmers to the same land and the same métier. At the zad, however, no such group was or is in a leadership position, and this has created, in the end, a very different and highly interesting kind of movement, one that in its desire to hold together the diverse but equal components that make it up, requires, as one zad dweller put it, “more tact than tactics.”5 An authorial collective at the zad, the Mauvaise Troupe, has given the name of “composition” to this art of creating and maintaining solidarity, over long stretches of time and innumerable challenges, out of the improbable encounters between people of disparate ideologies, identities and beliefs. Nothing in the way that these people come together and stay together over time adds up to a final orthodoxy—instead, the continuing internal eclecticism remains. Composition is just another word for the unexpected meeting of two very different worlds and the becoming-commune of those worlds. An ephemeral version of such “composition” occurred not only in Nantes but in the more familiar ’68 landscape of Nanterre as well. Henri Lefebvre used to say that May ’68 happened because Nanterre students were forced to walk through Algerian bidonvilles to get to their classes. The lived proximity of those two worlds—functionalist campus and immigrant slums—and the trajectories that brought students to organize in the bidonvilles and Algerian workers to worksites on campus, these precarious and ephemeral meetings (beset with all the incertitude, desire, empathy, ignorance and deception that mark such encounters) are at the heart of the political subjectivity that emerged in ’68. They are the laboratory of a new political consciousness.

Share article