The sociology of art is the area of social sciences with which Nathalie Heinich is most often associated. Works of reference in this field are books like Être artiste (1996, new edition in 2012), Le triple jeu de l’art contemporain (1998) and Le paradigme de l’art contemporain (2014), among many others about art and contemporary art disputes. But this sociologist, with a vast, diverse oeuvre on many subjects and in many genres, has also been addressing other matters for almost a decade now. In 2018, she addressed the issue of identity and its controversial definitions in a small book entitled Ce que n’est pas l’identité. This interview is about this book, along with her contributions as an intellectual to a heated and sometimes violent discussion that has dominated the public forum in France. But we must not forget that Heinich’s first incursion into identity issues (in this case, female identity) was a 1996 book entitled États de femme. L’identité féminine dans la fiction occidentale. From the time of writing of the book to the present day, there have been profound changes in feminism, which have sparked new controversies. And identity politics has caused veritable social and cultural upheavals. Heinich has taken a critical view of these upheavals, which necessarily generates controversy or even raises barriers.

In this interview, the French sociologist Nathalie Heinich, author of Ce que n’est pas l’identité, defends ‘universalism’ against the specificities of identity. Her public opinions have involved her in huge controversies. They can be explained by the way in which these issues, which were regarded for a long time by French intellectuals as a nefarious product of studies by American universities, have recently ignited a veritable ‘civil war’.

ANTÓNIO GUERREIRO Let’s start with your book titled Ce que n’est pas l’identité. Why define identity negatively, by saying what it is not?

NATHALIE HEINICH I have worked long and hard on the question of identity. My book États de Femme, on feminine identity in western fiction, dates back to 1996. I think that it is an extremely useful concept from a scientific point of view; an important analytical tool. But the past 20 years have seen increasingly politicised uses of this notion. In France, the notion of national identity was used by Nicolas Sarkozi and later the concept was taken on by the extreme left wing, through the importing of American trends that consist in allocating individuals to groups, to victimised communities, thereby developing a politics I call ‘identitarist’. And so now we have political, politicised uses of the notion of identity, on both the left and the right. I consider them to be highly reductive when one considers the richness of the notion of identity and they are founded on a totally erroneous conception of identity. So then I thought that it would be more pedagogical to root our approach in notions of identity that are extremely present in the public domain and, based on them, arrive at a positive definition of identity, rather than undertaking a systematic exposé of the notion of identity, as I would have done 30 years ago, before the word had been popularised in the public domain as much as it has been now. Let me give you an example: what ten years ago we called ‘culture’, from an anthropological point of view, we now call ‘identity’.

AG When you wrote États de femme. L’identité féminine dans la fiction occidentale, the issue of identity, in France at least, had not yet acquired the meaning it has today. What, then, was your theoretical framework?

NH My theoretical framework consists of a departure from a classical sociological categorisation, whether by social class or by gender, to introduce a more complex and subtle way of thinking about women’s differences in status. One of the problems of gender studies is that they take women en masse, as if all women shared in the same status. In États de femme, I introduced an internal category within women’s status, which I called ‘états’ (which would translate as ‘states’ in English), to explain that the different positions occupied by women in the possible spaces within feminine identity are extremely hierarchised and conventionalised, as may be seen in fiction. As such, the ‘first’, both married and a mother, is superior to the ‘second’, who experiences her sexual availability without being married and who is in turn superior to the ‘third’, who is financially independent but forced to give up her sexuality. Fiction gives us depictions of these status conventions at the heart of women’s status. The book was completely ignored by gender studies because it did not follow the same approach as they do, in as far as it does not globalise women’s status. Quite the contrary, it shows that there is division into quite different, hierarchised ‘états’. Furthermore, it wasn’t rooted in the idea that women are systematically discriminated against, alienated, etc., if only because they are the first to establish discrimination among themselves. This book is based on the notion of identity, not taken in a global and prescriptive sense, but through the examination of the different ways in which individuals perceive themselves, present themselves to others and are designated by others. So, in this book, I came up with a model that considers identity as a consequence of these three identificatory moments: self-perception, presentation and designation. This model differs both from the unitary model, which consists of thinking that identity is one, and from the binary model, so classical in social sciences, which consists of opposing one personal identity (deemed more authentic) with a social identity. I wanted to reject this binary model as implicitly prescriptive. And I have returned to this analytical model in my work on the identity of the artist and the writer. These are sociological works, in stark contrast to those undertaken by both politicians and militant academics (the ‘academo-militants’, as I call them), who use the notion of identity in a prescriptive sense, immediately allocating people to group categories, only taking into account one single dimension of identity and imposing this mark of identity on them, without considering the specificity of the contexts in which the identificatory process takes place.

"Now we have political, politicised uses of the notion of identity, on both the left and the right, highly reductive when one considers the richness of the notion of identity."

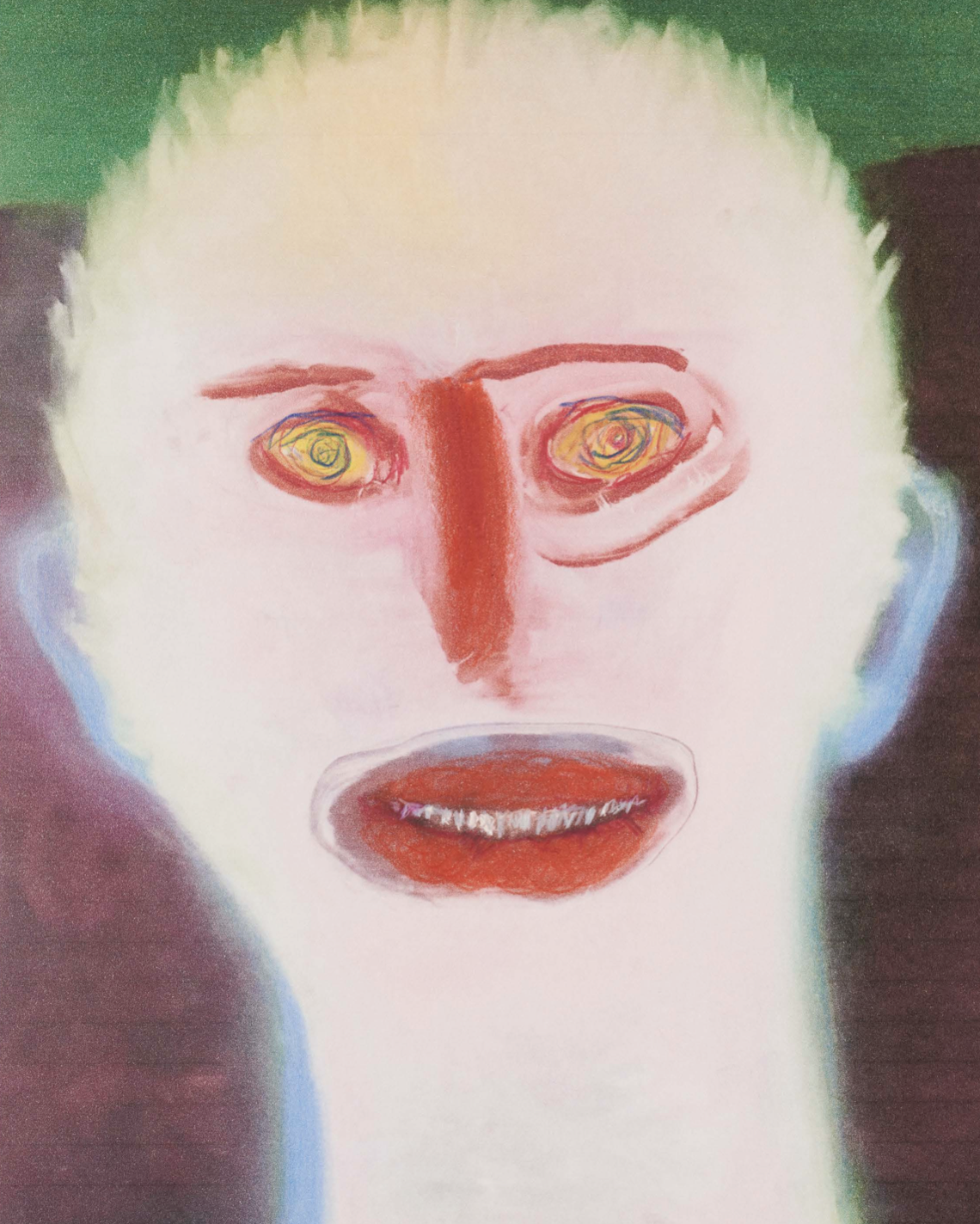

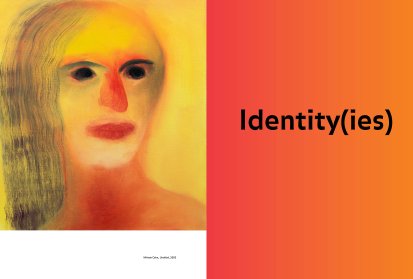

Miriam Cahn farbig [coloured], 2018 © Photo: Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Jocelyn Wolff, Romainville and Meyer Riegger Gallery, Berlin and Karlsruhe

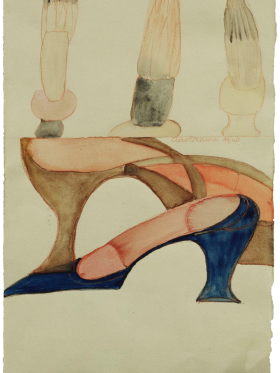

Hans-Jörg Mayer, Untitled, 1991

Courtesy of the artist

AG If one looks at it retrospectively, might one say that we have moved from reclaiming difference to reclaiming identity?

NH It’s more complicated than that. In Ce que n’est pas l’identité, I show that identity simultaneously means both difference, in other words specificity, and similitude: identity defined by differentiation and identity defined by assimilation. That is part of this notion’s extraordinary dialectic richness. In the ‘woke’ movement, increasingly widespread in the cultural and academic domains, the assimilatory and communitarian use of identity is prevalent and collective identities are considered regardless of the contexts into which individuals are inscribed. And domination occupies a central and even exclusive position in the description of this ‘community’, whether it be defined by gender, sexual orientation, race, religion or whatever.

AG Cultural studies and all their disciplines have played an important role in the current problem of identity politics. France has long resisted the introduction of many such ‘studies’, imported from the United States, but it appears that the situation has changed in recent times.

NH There is still some resistance, thankfully. For example, I am part of a group of university academics called the ‘Observatory of Decolonialism and Identity Ideologies’ (with a website: decolonialisme.fr), where more and more of us are speaking out against the harmful role of these ‘cultural studies’ in terms of the quality of what is produced in the social sciences. But this vogue originating in the United States has spread extremely quickly, bulldozing all obstacles, and it is not easy to resist, firstly because there is a fashion and intimidation effect, as well as a blame effect, as any rejection of the relevance of an approach to phenomena using the identity-based filter quickly exposes you to accusations of racism, sexism, homophobia or even, simply being ‘right-wing’, even though a great number of us consider ourselves to be to the left of centre. Most of us are opposed on grounds linked to the quality of the academic work and research produced and not for political reasons. What we take issue with is purely and simply the reduction of all forms of research to political activism, to the detriment of science and the production of knowledge.

"The assimilatory and communitarian use of identity is prevalent and collective identities are considered regardless of the contexts into which individuals are inscribed."

AG This is the concern that leads you, in your book, to vehemently defend the principle of axiological neutrality...

NH Absolutely. I have always been faithful to that neutrality in my sociological work, including in my work on contemporary art, which is a tad complicated as it is a minefield. For me, that neutrality is absolutely fundamental, and it’s what I defend in the brochure ‘Ce que le militantisme fait à la recherche.’ I advocate this for reasons that are not political, but scientific, for reasons that are related to the quality of the science and the autonomy of knowledge, as opposed to militant objectives which, in my opinion, have no place in the world of research. France has put up a degree of resistance to this trend, as it has a universalist tradition and we feel that in our republican system, individuals, citizens, are not defined by their belonging to a limited community founded on criteria such as gender, race, sexual orientation etc. We are absolutely against militant communitarianism and I think that this universalist culture gives us the intellectual and political means to resist this ‘woke’ invasion, not on behalf of a right-wing position refusing all progressive options, but in the name of an age-old tendency of the republican left. There are two opposing positions at the heart of the left: on the one hand, the radical left, which I call ‘identitarist’, totally dominated by the community-oriented woke movement and, on the other, the republican left, universalist and secular.

[...]

Share article