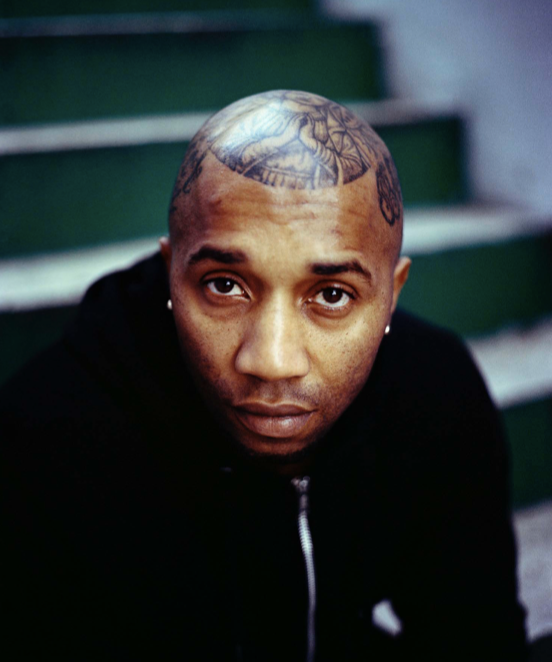

This piece draws on four artists – Ghoya, Mynda Guevara, Né Jah, Primero G – essential parts of creole rap, to tell some of the many stories of the Greater Lisbon area and the South Bank. I took inspiration from them, the neighbourhoods where they grew up and the interlocutors suggested by them, to create a cartography that has been their local everyday life since the revolution of 25 April, 1974, and that portrays the indivisible reality of the music that they make. These four artists participated in a concert and conference on 5 July, 2020, when the independence of Cape Verde was celebrated, within the Terra Irada [Irate Land] programme, which I developed for MAAT in that peculiar year. After gladly accepting Electra’s invitation to write a piece, I immediately wanted to continue exploring the subject through this medium.

Portuguese creole rap, which arose in the 1990s, is a programmatic and natural affirmation of the Cape-Verdean language within Portuguese rap and hip hop. It is a very long story that has only recently received proper attention and dissemination. For pluralist, micro-generational and age- related reasons, these are four figures who, in the eras when they emerged, affirmed new ways of being here, using language, parity and activism in equal measure. Each one maintains their complete artistic and civic pertinence, as well as a fierce independence. This is perhaps the most popular music in our country today, although you cannot listen to it on the radio or buy its albums in the few places that still sell physical records. By definition, it is the most relevant representation of the music of the young Portuguese working class across the country and one of the most cherished and listened to by teenagers from the North to the South.

Broadly speaking, the text strives to provide a record of the interview process. In using this technique, many conversations that determined the interviews have disappeared. What remains are edited (typed) statements on the many issues that were addressed, around the origins of the music itself and the areas that influenced it.

The piece is divided into the neighbourhoods where each artist grew up, or in Ghoya’s case, the neighbourhood that he chose for this purpose, among the many others where he has spent his life. Né Jah, who has lived in Paris for many years, was not in Portugal when these interviews were conducted. Instead, Diogo Simões and I spoke in person with his younger brother, Bebe, at his own suggestion, in the house where the two of them grew up with another brother. In the case of Primero G, Arrentela is his second long-term location, after spending a large part of his life in the Pedreira dos Húngaros neighbourhood, now demolished. Of the four, only Mynda grew up and remains in Cova da Moura.

I chose to disappear from the transcribed interviews as much as possible, only making an appearance when I believed it was necessary to impart rhythm and fluidity to the reading of the piece.

I found it extremely difficult to make cuts to the interviews and quotes, which has always been a problem for me. It is stifling (that is the proper word) to discard a series of remarkable arguments, deeply rooted in reality. The work of choosing between these fragments initiated, and in the end formed, the architecture of this piece. I will conclude by saying that for this oracle of subjects no number of pages is enough.

Share article