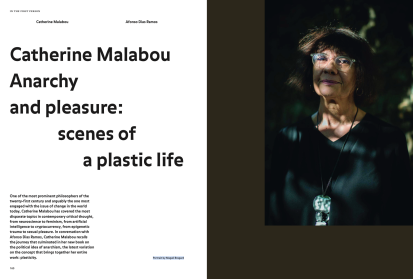

Catherine Malabou is a prominent figure within contemporary European philosophy and is widely regarded as one of the most exciting names of the so-called ‘New French Philosophy’. A specialist in contemporary French and German philosophy, Malabou is praised for some of the most original readings of canonical thinkers such as Hegel, Heidegger and Kant, and is increasingly acclaimed for pioneering the dialogue between the traditional social sciences and the hard sciences, probing the unexplored relationship between neuroscience, philosophy and psychoanalysis. The rare case of a philosopher engaging with life sciences, Malabou has undertaken a radical reading of figures from Freud to Spinoza or Kafka from the viewpoint of contemporary neurology and maintains that we have yet to assimilate the revolutionary discoveries made in biology over the last half a century. A prolific author since the late 1990s, Malabou’s work continues to take unexpected directions, from exploring the concepts of essence and difference within feminism to questioning the place of the feminine in philosophy, from creating a new theory of trauma to calling for a redefinition of the subject, from artificial intelligence to cryptocurrency, from epigenetics to anarchism. This entire work is essentially a long and consistent attempt to reconsider ideas of mutation, metamorphosis and transformation, rendering Malabou one of the preeminent thinkers of change today. The central concept in her work is plasticity, a term initially taken from continental philosophy but developed over the last two decades in proximity with neuroscientific studies of the brain. Plasticity refers to the coexisting power to give, receive, explode or regenerate form, the ability of any form to be transformed and to transform itself. Such a concept is flourishing within contemporary social, economic and political discourses, mobilised repeatedly for rethinking politics, literature, art, law, and justice. At a time when corporations and governments insist on the mantra of flexibility, this philosopher calls us to develop new forms of sociality and modes of being, reinvesting in the constitutive plasticity of the human being as a ‘principle of internal disobedience.

Catherine Malabou is a Professor of Modern European Philosophy at both Kingston University (UK) and the European Graduate School (Switzerland), and Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of California Irvine (US), a position previously held by Jacques Derrida, her former supervisor and interlocutor, with whom she co-authored Counter-Path (1999). Among her most important books are Plasticity at the Dusk of Writing (2004), What Should We Do With Our Brain? (2004), The New Wounded (2007), Changing Differences (2009), Ontology of the Accident (2009), with Judith Butler, You Be My Body For Me (2012), with Adrian Johnston, Self and Emotional Life (2013), Before Tomorrow (2014) and Morphing Intelligence (2017). In her previous, polemical book, Erased Pleasure (2019), Malabou focused on the clitoris as a pleasure island systematically obliterated by patriarchal societies, not only as the sexuality of the female body but also in psychoanalysis and philosophy. It was but a prelude to a newly released book, Au voleur! Anarchisme et philosophie (2022), which calls for a totally new philosophical elaboration of the idea of anarchy, as something that is more politically urgent than ever. Catherine Malabou talks to Electra about some of the new challenges and directions in her own thinking.

Share article