In his eponymous essay The Angel is my Watermark, the adulterous mystic bard Henry Miller makes a cause for the attainment of grace as analogous to the capacity to observe life as it comes, without the will to stage the beauty which defines it implicitly. Which artistic medium is based entirely upon the radical confirmation of observation? Photography. The history of photography has faced a series of tensions which both define its utility and subjugate its authenticity. It has been analysed through lenses which place it as a representational effort, as a failed act of capturing the ever moving, as a censoring medium, and above all, as a substitute for the limitations of optical perception. It is all of these things and more.

Yet, what is interesting is to reflect upon the ways in which complex knowledge can be generated through photography as the consequence of a curious will of the photographer, and in this sense a desire to bridge the gap between the mysteries of the body and the habitual flows of life. Is it possible to look at a photograph formally to the same extent that it can be viewed as a transmission of knowledge? To be rhetorical, the question is raised here: what aspects of a photograph can inform change in the viewer through her acquisition of access to what the image proposes? Then again, as we are given the ‘punctum’ of Barthes: what draws the eye to a part of a photograph that escapes definition, and thereby allows for elaboration? Any photographer that can master the honest and generous offering of ‘punctum’, is one to watch. In his 35mm colour slide installation from 2011, The Reader2, the Uruguayan artist Alejandro Cesarco offers the notion that ‘a genre is a perspective from which to ‘read’. This brings us directly to locating those individuals who can be called pioneers on the basis of their unequivocal perspective, consistently expanding its scope and undoubtedly prophetic: those who invite participation.

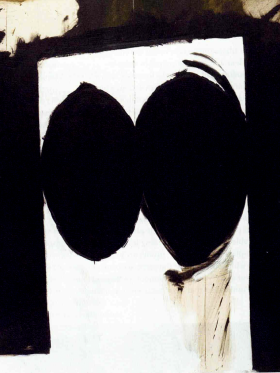

Viviane Sassen, the artist, the photographer, the figure: creator of genre. The merging of the fashion and fine art photography worlds has been achieved by few, and Sassen is at the forefront of this movement, to the delicate extent that she eschews categorisation. Above all, she remains the engine behind a kinetic aesthetic which simultaneously emancipates the body in an industry based upon its violent gendered repression and gives ‘still life’ a joyful place within contemporary photography. Sassen cites surrealism as one of her earliest artistic influences. This is of particular interest, since the baseline of the surrealist project is the exercise of temporal fragmentation. So to speak, the taking of object, environment, colour, and horizon, each into their own time signatures, thus rendering a visual journey backwards and forwards through time. Another defining feature, as considered by Lautréamont, is the placement of beauty as an output of a particular kind of seeing the parts of something, instead of glossing over its wholeness. ‘Beautiful… as the fortuitous encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table’3. Sassen has a special way of cropping all that is unnecessary for a process of learning, out of the frame, and in this sense, dissecting the elements of what she photographs surrealistically.

Traditional Ikebana was meant to mimic life in the way it unfolds, and thus possess asymmetry. These flower arrangements were seen as the evidence and means of meditation on simplicity. The practitioner of Ikebana was required to enter into a state of mindfulness before proceeding with the choosing of flowers and other natural elements. Thus, the craft itself was inextricable from the interiority of the practitioner. There is a parallel between Sassen’s work and Ikebana such that asymmetry is employed as a means of honouring complexity and engaging with that which justifies realism. Thus, there is a unique ricochet in Sassen’s work between the surreal and the real. Once one is implemented in the photography, the other enters and vice versa.

In terms of travelling between universes of affect, Sassen, in an interview with Sean O’Hagan for The Guardian says that she is ‘…putting one foot in an unconscious world. I am trying to evoke that parallel universe I experienced as a child and that I could not find when I came back to Holland. All artists, to a degree, make self-portraits – that is what I am doing in my own instinctive way.’ Sassen, who was born in Amsterdam, also lived in Kenya as a child and continues to work in Africa. This movement out of the occident and back into the occident informs her work. The disavowal of autobiographical resonance in artistic production is ultimately pretentious. As Sassen acknowledges, it is in the very reflection of her process of growth that something wider sociologically is cultivated.

For this edition of Electra Magazine, Sassen has prepared a series of recent works, published here for the first time. They are taken as individual documents, as points of light, as petite stories with resonance. Naturally, they can also be read in an order, but that is the consequence of a certain appetite for narrative. One of the outstanding qualities of these photographs is that they need no description, and in this sense their worldliness is otherworldly. We return to attuning with the idea of ‘looking the world in the face’, making eye contact with what is before oneself. The fine and almost totemic play between photography and painting in these images is also a testament to the gentle undoing of expectation. Ultimately, colour and attitude manifest to satisfy the strong desire for freedom through form. Sassen’s exceptional contribution falls in line with the Russian adage that ‘the appetite comes with eating’. The more these works are experienced, the hungrier we are for their rare and delicious lingering on the palette. Delightful. Necessary. Bold.

Share article