‘It seems to me that every step forward is also a step backward. Progress always exists in only one particular sense. And since there’s no sense in our life as a whole, neither is there such a thing as progress as a whole.’*

Robert Musil, author of The Man without Qualities, with his critical attitude of Viennese modernism, expressed huge scepticism about the idea of progress. Dario Gentili, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Roma Tre University, examines and comments on this idea.

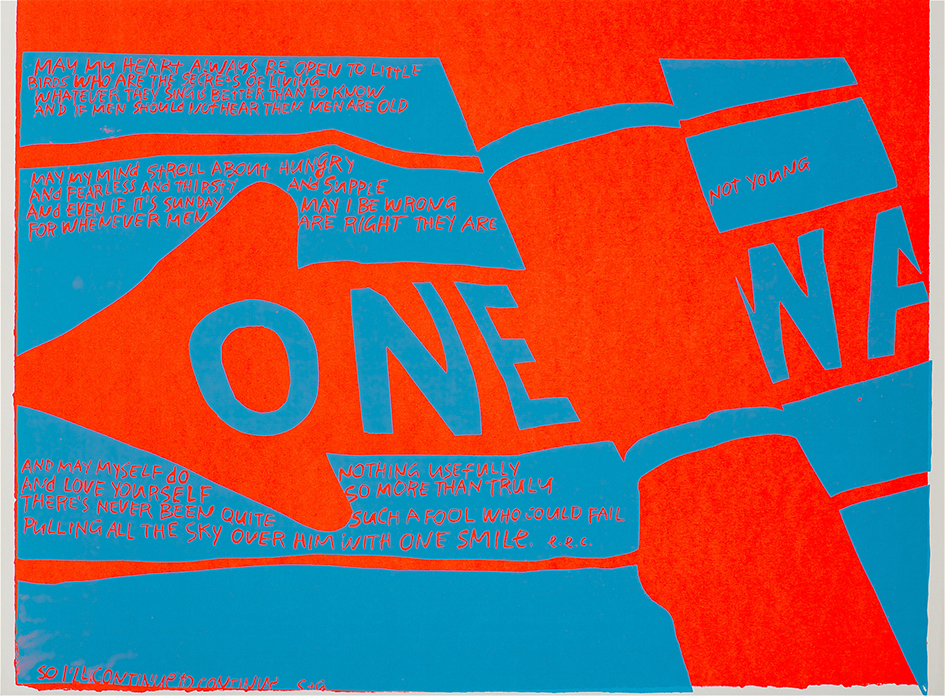

Corita Kent, One Way, 1967 © Courtesy Corita Art Center and Kaufmann Repetto

‘There’s no sense in our life as a whole’, maintains Ulrich, the protagonist of The Man Without Qualities by Robert Musil. That is why life does not entail progress or rather – to keep to the customary and accepted meaning of the term – it does not make progress towards something better. Consequently, the conditions of life of humanity do not improve from age to age or from generation to generation. Only a few decades ago, Musil’s words, so steeped in nihilism and decadentism, might have seemed relevant to an antimodernist minority, but certainly did not reflect general sentiment. Now, however, how many of us would feel confident in declaring our faith in progress? Put another way, how many would assert, without fear of being proved wrong, that today’s children will have a better quality of life than their parents? How many would claim this in the current context of a crisis that is at the same time social, economic, health-related and ecological?

Nevertheless, it would be reductive to interpret Musil’s words as expressing exclusively the opposition between existentialism (the sense we have of life) and modernism (belief in progress). Rather, his statement reveals the overlap, if not actual confusion, between ‘sense’ and ‘direction’ that has favoured the concept of progress from the nineteenth century onwards: a certain direction in the course of the evolution of humanity has ended up colonising the sense we have of life. From the perspective of progress, life only has sense if it continues in the direction that has already been mapped out. It is therefore not life as a whole that has sense, but only the form of life that pursues the established path. Progress thus follows a continuous line, where each step forward gives sense to the step that immediately preceded it and vice versa. This is how the onward course of history is configured, and how it ends up coinciding with the meaning of history. Discontinued paths – those that are no longer chosen – are doomed to oblivion together with the steps that had hither to travelled along them. From among all the available routes existing from age to age and from generation to generation, progress chooses the trunk road, which it therefore must continue to follow.

I am persisting with the metaphor of the path, the route, the road, because it is suggested by the etymology of the term ‘progress’. ‘Progress’ comes from the Latin verb progredi, which means ‘to walk forward, to advance’. This is the same etymology that applies to Musil’s German term: Fortschritt is, in fact, even more specific, indicating the ‘step forward’ in the direction of travel. To maintain, as Musil did, that progress (Fort-Schritt: a step forward) and regress (Rück-Schritt: a step backward) are equivalent means simply that life, as a whole, does not follow any predetermined direction: if no path is mapped out, it is impossible to go either forwards or backwards. So, if life has no sense, is it senseless? This is the nub of the very modern problem of progress. If sense and direction coincide, if life only has sense when it follows a certain route, then the moment one looks at life outside and beyond the path of progress, it appears senseless.

This is the view of Ulrich, who believes himself to be ‘without qualities’ to expend and invest on behalf of the progress of humanity; in other words, he does not believe he has the ability – today we would say competency or skills – required to live in a society governed by progress. He does not move ahead in his life: he remains standing in one place. His life is senseless because it does not assume the predetermined form. The form of life prescribed by progress leaves no room for alternative meanings.

[...]

Share article