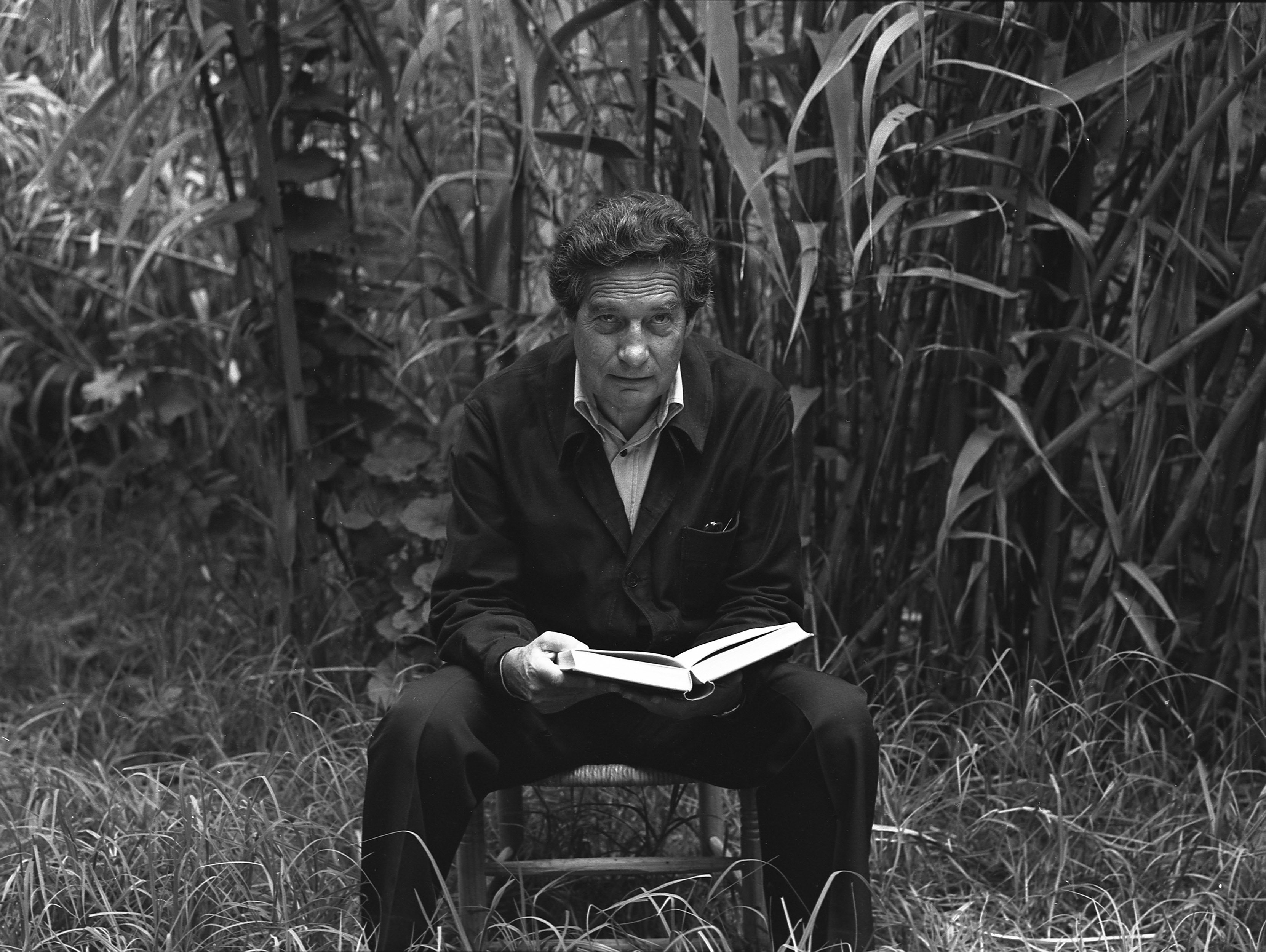

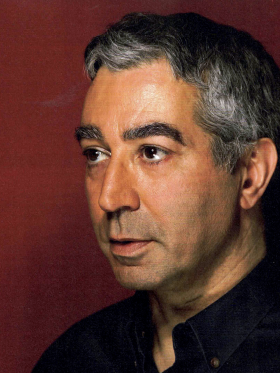

Octavio Paz belongs to the modern tradition of critical poetry, exemplified at the dawn of modernity by Charles Baudelaire (whose work as an art critic was the subject of an insightful essay by Paz in 1967) and later by J.K. Huysmans and other Symbolists; by Guillaume Apollinaire, Blaise Cendrars and other Cubists, and by André Breton, Louis Aragon, Paul Eluard and other Surrealists. The tradition was perpetuated by a variety of figures from the French post-war generation: Yves Bonnefoy, a good friend of the Mexican poet; Michel Tapié, the founding father of art autre; Julien Alvard, who invented nuagisme, and the Telquelian Marcelin Pleynet, who coined peinture-peinture. In the United States, it was embodied by John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, and, latterly, by John Yau and Vincent Katz. The tradition proved rather less popular in Hispanic circles, although it was endorsed by some particularly prominent poets: Ramón Gómez de la Serna (who Paz greatly admired), Guillermo de Torre, Juan-Eduardo Cirlot, Ángel Crespo, and, nowadays, Andrés Sánchez Robayna, Enrique Andrés Ruiz and Enrique Juncosa in Spain; Aldo Pellegrini in Argentina; Severo Sarduy in Cuba; Juan Calzadilla and contemporary poet Luis Pérez Oramas in Venezuela; Joâo Cabral de Melo, Ferreira Gular and the Augusto de Campos brothers in Brazil.

look for Paz’s Complete Works on my bookshelf, finding my Barcelona edition from Círculo de Lectores, and open the two volumes in which the poet’s essays on art are compiled under the Gongoristic title The Privileges of Sight. He wrote more on the subject after the compilation was published and there are likely to be a few texts lost in the labyrinth of his papers, but these pages contain the essence of Paz’s fascination with the work of visual artists, which he expressed in prose and, more occasionally, in verse.

Share article