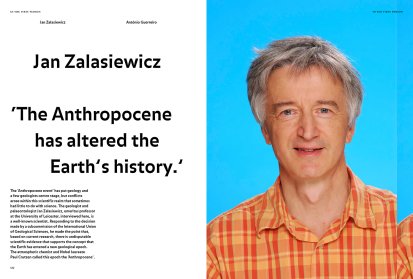

Jan Zalasiewicz is a renowned geologist and palaeontologist, emeritus professor at the University of Leicester. The history of Earth’s environments (surface and subsurface) spanning half a billion years is his main interest. His scientific insights are presented in books such as The Earth After Us: What Legacy Will Humans Leave in the Rocks? (2008) and The Planet in a Pebble: A Journey into Earth’s Deep History (2010). For some time, he has focussed on the Anthropocene concept, both on a scientific and on an institutional level. In 2008, as Chair of the Stratigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of London, he led the results of a year-long research exercise to a journal of the world’s largest geological association, the Geological Society of America. This was published as a question, prompting a debate that would not stop growing: ‘Are we now living in the Anthropocene?’

In the beginning of March of this year, Jan Zalasiewicz became well-known beyond the narrow circle of his scientific milieu when he publicly contested a vote organised by members of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS), which is part of the International Commission on Stratigraphy, the body that supervises the Geological Time Scale. The events that led to this highly publicised protest are well-known and made headlines all over the world. The Anthropocene Working Group had spent more than a decade analysing the question of whether we have entered a new geological epoch marked by the irreversible action of humankind on the fundamental systems of our planet. After gathering abundant scientific evidence, they wrote a proposal that recommended official recognition of the Anthropocene concept. Most of the members of the SQS then rejected, with little discussion, this proposal to officially declare the Anthropocene as a new epoch of geological time. Jan Zalasiewicz formally protested the voting process, noting how the official Statutes of the International Commission on Stratigraphy had been violated in the process. He stated that this rejection vote should be annulled, considering the manner in which it was obtained. For the public what remained was this strange news: that the Anthropocene concept, which has entered everyday language and is legitimised by a vast bibliography, had been rejected by a group of scientists who had the power to make it official.

In this interview, Jan Zalasiewicz speaks about this incident and its consequences. At the same time, he makes clear that despite not being an official designation, the Anthropocene represents the reality of the colossal challenge faced by humanity today.

Share article