introduction

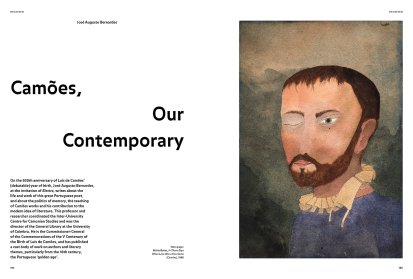

On the 500th anniversary of Luis de Camões’ (debatable) year of birth, José Augusto Bernardes, at the invitation of Electra, writes about the life and work of this great Portuguese poet, and about the politics of memory, the teaching of Camões works and his contribution to the modern idea of literature. This professor and researcher coordinated the Inter-University Centre for Camonian Studies and was the director of the General Library at the University of Coimbra. He is the Commissioner-General of the Commemorations of the V Centenary of the Birth of Luis de Camões, and has published a vast body of work on authors and literary themes, particularly from the 16th century, the Portuguese ‘golden age’.

Mário Botas, No tempo que de amor viver soía (Camões) [In Those Days When Love Was a Fine Game (Camões)], 1980 © Photo: João Neves / Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea – Museu do Chiado, Lisbon

Although they often may not seem straightforward, the politics of memory follow some general principles. We know from the outset that celebrations of the past are (all of them) designed to draw attention to the present. It can’t be otherwise: the past that is being evoked is constructed and reconstructed according to the needs of the moment.

The second principle has to do with what (or who) is being celebrated. Honouring a person involves more risks than commemorating an event. Celebrating a public figure often implies silencing those aspects that may break the consensus. So it is with most heroes, even if they are from a very distant past. That is true, for example, of such Portuguese figures as Nuno Álvares Pereira, Vasco da Gama, Father António Vieira, and the Marquis of Pombal, to name but a few.

Yet none of this is true of Luís de Camões, the poet who was born five hundred years ago.

Although still unsure as to which model or direction the celebrations will follow, Portugal is preparing to mark this milestone commemoration of Camões’ persona, his literary achievements, and his singular times – the ‘golden’ sixteenth century. It’s high time to try and pinpoint the facts that explain the exceptionality of Camões. Not least because, in the case of this great poet, his aura encompasses not only collective life, but also such areas as education, history, culture and aesthetics.

public acclaim

the signs

In 1580, Luís de Camões died in Lisbon, possibly in a hospital, from venereal diseases. His death was almost unacknowledged. Some find this anonymity odd. After all, the publication of his epic Os Lusíadas [The Lusiads] should have earned him greater recognition.

He did receive some recognition, however, albeit discreet. We know of the praise given to Camões by Pero de Magalhães Gândavo, a humanist and grammarian, in his Regras que Ensinam a Maneira de Escrever [Method on how to write]. In this work, printed in 1574, Gândavo refers to the poet as ‘our famous poet Luís de Camões, against whose fame Time will never triumph’. Gândavo was also the chronicler of Historia da Província de Santa Cruz [History of the province of Brazil], a book that contains the only two poems by Camões printed after 1572. The Historia was published in 1576 by António Gonçalves, the same typographer who had printed The Lusiads four years earlier.

Another sign of importance and acclaim is the almost simultaneous printing of two Castilian translations of Camões’ epic (in Salamanca and in Alcalá de Henares), both dating from 1580. They seem to have been sponsored by king Philip II of Spain. Supposedly, the Salamanca edition, translated and annotated by Bernardo Gómez Tapia, ended up in Camões’ hands.

And finally, there is the pension, which amounted to fifteen thousand silver reais. It was awarded to him by the Crown in his dual capacity as a soldier and a poet. Although relatively modest, and paid at irregular intervals, it nonetheless represented a fairly uncommon seal of approval.

Mário Botas, Que poderei do mundo já querer (Camões) [What Now in This World Could I Long for (Camões)], 1980 © Photo: João Neves / Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea – Museu do Chiado, Lisbon

"Other prominent authors from this ‘golden age’ (such as Gil Vicente and Sá de Miranda) were also republished, but in an intermittent and volatile form. Only Camões’ oeuvre has been printed without interruption from 1572 to the present day."

True, the signs are few and have different probative values. Public acclaim would come only after his death and was primarily expressed in the continual reprinting of his books. It was through the printed word that a writer’s fame was established, and in fact it is safe to say that no other Portuguese author has had such an exceptional and intensive publishing history. Other prominent authors from this ‘golden age’ (such as Gil Vicente and Sá de Miranda) have also been republished, but in an intermittent and volatile manner. Only Camões’ oeuvre has been printed without interruption from 1572 to the present day.

The most recent sign that Camões’ legacy is still very much alive in the public space came recently from an unexpected quarter: the decision to name a new Portuguese airport after him. The location of this infrastructure has been the subject of one of the most lengthy and enflamed controversies over the last few decades. Both in and out of the electoral arena, political parties have promised to make firm and technically sustainable decisions. Then, a few days after taking office, the current government finally decided on its location. Even though the construction period is expected to last for at least a decade, its name was announced immediately. This move can only have one meaning: the name of Camões continues to quell controversy. The fact that his name is associated with a place of arrivals and departures is well accepted in 21st century Portugal.

In addition to these signs, others occur that are less noticeable because they have become routine. Such is the case of the State Protocol that has made visiting Camões’ tomb at the Jerónimos Monastery a recurrent ritual. Most recently, on July 12, Infanta Leonor de Borbón y Ortiz, heiress apparent to the Spanish throne, began her visit to Portugal by laying a wreath at the poet’s tomb.

[...]

Share article