In 2024, at the age of 94, Isabella Ducrot has had two museum shows this year alone: at the Consortium Museum in Dijon and the Museo delle Civiltà in Rome. She has also exhibited internationally with Petzel in New York, Sadie Coles in London, and, her primary gallery, Gisela Capitain in Cologne. While personal and intimate, her artistic practice explores cultural history and mythology and reflects her passionate engagement with textiles. Nora Iosia, Isabella Ducrot’s studio manager, met us at Piazza del Collegio Romano for the interview. She guided us into the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, leading us through the arcades along the courtyard to Isabella’s ground-floor studio. We were warmly welcomed by Veronica Della Porta, the studio assistant, and Isabella Ducrot, who greeted us with coffee and praline di cioccolato.

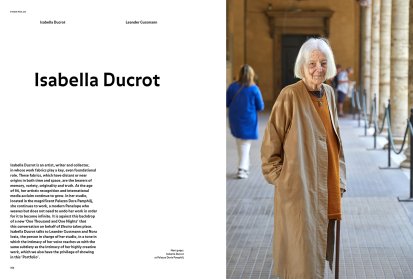

Isabella Ducrot is an artist, writer and collector, in whose work fabrics play a key, even foundational role. These fabrics, which have distant or near origins in both time and space, are the bearers of memory, variety, originality and truth. At the age of 94, her artistic recognition and international media acclaim continue to grow. In her studio, located in the magnificent Palazzo Dora Pamphilj, she continues to work, a modern Penelope who weaves but does not need to undo her work in order for it to become infinite. It is against this backdrop of a new ‘One Thousand and One Nights’ that this conversation on behalf of Electra takes place. Isabella Ducrot talks to Leander Gussmann and Nora Iosia, the person in charge of her studio, in a tone in which the intimacy of her voice reaches us with the same subtlety as the intimacy of her highly creative work, which we also have the privilege of showing in this ‘Portfolio’.

Isabella Ducrot at Palazzo Doria Pamphilj

Isabella Ducrot's studio

© Photos: Simon d'Exéa

Leander Gussman A wonderful place. Since when have you had your studio here?

ISABELLA DUCROT For about 20 to 25 years. I also live in the same building, that’s why I can continue working. I hardly leave the house. This is a privilege; naturally, it is very quiet, and I can come to work in the studio.

LG And you all meet here daily?

NORA IOSIA Yes. We have worked together for 28 years. It feels like we grew up together. Isabella and Veronica meet every day at 09:30 and work on the pieces until lunch. During this time, I take care of all relations with galleries, museums, and institutions, and then, around 11:30, I usually join them to talk and organise things together.

LG You were also helpful in setting up the interview.

NI Thank you, yes, with the Gallery Gisela Capitain.

LG whole team. When did you start working with Gisela Capitain, a legendary German gallerist active since the mid-80s?

ID Gisela came to visit my studio five years ago when I was 88. The extraordinary thing about this situation is that I do not regret that it was so late. Now, I barely extend the present. My time is every day, and I enjoy life in the present. So, she found me through a book I had published with Sylph Editions from London, Text on Textile, a small selection of my writings published in their Cahier Series. We met, and then she immediately took risks and showed my work during the Art Basel in 2022. Now, everything passes through Gisela. I am not a faithful person, but I want to be faithful to her.

NI I agree that now, with the attention to Isabella’s work and several international exhibitions, a well-functioning system is essential. Gisela exemplifies this, possessing both an excellent mind and a remarkable spirit. I want to emphasise this point: her intellect and soul harmonise, allowing us to balance business acumen with genuine desire. This combination, I believe, is crucial. She operates very effectively, and together we maintain a shared direction.

LG Your work is manifold; there are paintings, collages, books, and other forms. But some motifs and themes repeat and continue.

ID In a way, the subjects are always the character of textiles. I reflect on this all the time. I am obsessed and I have tried to observe as much as I could. Textiles carry many meaningful symbols for everyday life, so it is a continuous understanding of those structures and meanings. When I was a young girl during the war, fabrics were an important part of our lives. We never threw away anything. We mended and recycled cloths at home. Today, mending almost no longer exists. People do not understand how or why they should repair anything if they can buy something new.

LG Cristina Bomba, from Atelier Bomba, the exceptional clothing store in Rome, told me she saw a patched blanket that you had made to use at home. She then tried to convince you to start making more and ordered two folding screens for her shop.

ID Cristina is my friend. This was about 40 years ago. Things happened very slowly. I knew many painters and writers. In a way, it was not easy to begin so late in my life. Nevertheless, I started with writing and doing other things connected to textiles. Then, my textile works had no followers. It’s a different culture today. Just some weeks ago, the Washington Post published an article on the current popularity of textile art1, but back then, this was not recognised so widely.

LG Patience plants roses. When did you start collecting textiles?

ID The collection started slowly and now I rarely collect. But I sometimes use precious pieces for my work. The collection, as it is today, includes rare and expensive textiles as well as more personal items. It’s about half and half. For example, Tatiana Twombly’s dog destroyed her Shahtoosh shawl, and she gifted me the remaining pieces. She told me, ‘only you would use it’.

LG In your book Stoffe, you differentiate between collections and raccolta, which translates as gathering, highlighting the more personal and intimate dimension of your practice. What about the other collections? I’ve read that you maintain a rose garden in Umbria with hundreds of different varieties. Also, your husband Vittorio Ducrot and you collected Baroque and Indian paintings.

ID Yes, it is true, we collected some Baroque and Indian paintings. We also gathered lots of roses.

LG One theme I see in your work, especially in your paintings, is that besides showing us the manifold forms of the textiles, you explore connections, of humans, and, in the case of weaving, of yarn. Then, in a recent series of paintings, the motif of tenderness, which such connections can hold, seems important.

ID There are themes of eros and tenderness. I was not looking for tenderness as a programme, but it came out as people in love.

LG The figures in the paintings hold each other and are central to an otherwise calm background. In many other paintings, usually the nonfigurative, some internal frames and borders are integral to your composition. They hold the motif, which is often a pattern, that appears regular and irregular simultaneously, through its hand-painted forms and colourings. How do you structure the images with those printed or painted frames?

ID I found these old carved wooden blocks for block printing in India. I started collecting them; some of them I bought were very old. When working, I use those old blocks and print the borders you find in many of my works. It became something of a signature.

LG Besides the geometric patterns of round shapes and stripes that often appear in your recent works, the grid is significant. It ties into several other themes and issues.

ID I wrote about patterns in The Checkered Cloth.

LG Yes, while reading, I thought about the Harlequin pattern related to checkered fabrics. It is simple with contrasting diamonds. It cannot be taken seriously. It is not used for expensive clothes. It is used in the theatre. Usually, the fool or Harlequin wears it.

ID In Europe, checkered fabrics are used in the kitchen and as practical cloth for working class women. I was curious about this. I observed that it is different in Japan. Textiles associated with status and wealth did not show the material’s structure. You will never see the structure of the fabrics and how they are made. The structure is the scandal.

LG Women in Europe are famously associated with weaving, a craft also connected to Greek mythology. You have Penelope’s weaving, as it is recounted in the Odyssey. We also know about Arachne challenging the goddess Athena to a weaving contest.

ID Women are primarily connected to textiles here in Europe. In India, it is different. Men are also associated with them. You have the mystic poet Kabir, whose father was a weaver, and his father’s craft influenced this talent. So, in India, there is a strong connection between weaving and poetry. The structure of plain textiles is similar to the logos and connected to rational thinking, language, and mathematics. Plato also used the metaphor of fabrics and weaving in his text on the Statesman.

LG What about stripes?

ID Ah, yes. The French historian Michel Pastoureau wrote an impressive book about its symbolism: The Devil’s Cloth: A History of Stripes and Striped Fabric. In a way, he also wrote about the scandal of the structure. Precious textiles usually imitate nature, and their colours, patterns, and motifs are taken from nature. So, in contrast, simple geometric shapes, like checks and stripes, were considered crude and of low status.

LG Interesting. It’s difficult to understand today why the structure had to be hidden. Textiles seem to be intricate structures that demand skill, mathematics, and sophisticated tools.

ID Unlike knitting, which only uses one thread to begin the work, woven textiles are made with a warp and weft and interlacing multiple threads; hence, their structure cannot be easily returned to the beginning. I have written about it in one of my books. Men usually did not know about this. Homer did not. Otherwise, he could not have written the story of Penelope, undoing her weaving every night, which is practically impossible.

LG I suppose, sophisticated literary text like the Odyssey follow an aestheticism that can be blind to the reality of everyday experience.

ID When I was in Turkey, I found fabrics that women there were making. I remember I saw them first on the floor of a market. They were simple fabrics; peasants made them. And at the time, my husband asked me why I liked them. I answered, ‘look, they are extraordinary. They have the forms of Picasso.’ In the catalogue ‘Variazioni’, from 2008, you have the images of the works in the exhibition, where there are embroidered handkerchiefs by women from Turkey, usually poor, and then men looking at the people. For those paintings, I copied these oya handkerchiefs with lace and embroidery. So you see the real handkerchief and my devotion and recognition – a simple copy. At the same time, I also painted men, composers like Stravinsky, who took the music from peasants and popular culture, stole the people’s work, and brought it to the concert hall without acknowledging them. We will never know the names of those women who made the fine embroidery I showed there, but it was important for me to recognise them.

LG Beautiful, this also relates to what you mentioned before: the woven textile structure is created by multiple threads, not by one.

ID Yes. These fabrics are fantastic. I saw their beauty. In my generation, folk and popular crafts were not considered art.

LG These traces of folk art were often erased. Also, I can relate to your gestures of repetition and mimicry. At University, I taught a seminar titled ‘Learning by Heart’. In this course, the objective was for students to copy and learn an existing work by heart. This approach countered the common inclination among art students to aim for originality and novelty, an idea I picked up in George Steiners’ texts on criticism. This brings me to a question about your writing processes. I’ve read you write in the mornings. What drives your writing and how did you start publishing books?

ID I met the publisher Stefano Verdicchio, of Quodlibet edition, because, at the time, he was making a catalogue for my husband about Baroque paintings. Only later did I produce these books together with him. I continue to write. In a way, I go on with textiles, and continue to be obsessed with textiles. So my obsessions are the same, especially since fabrics are disappearing. Plastic is too good. You can do everything with it. It seems we do not need natural textiles any longer. So currently, I am preparing a new book; again it will be on textiles.

Isabella Ducrot, Small Tendernesses VII, 2021

© Photo: Giorgio Benni / Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Share article