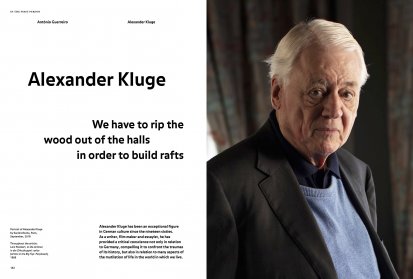

As a major figure of German culture since the 1960s, Alexander Kluge would have to be introduced under a multitude of names: a writer, a filmmaker, a director and a producer of cultural television programmes, an essayist, the author of books of social theory born out of the intellectual circle of sociological and philosophical research that he was a part of – the Frankfurt School. It was within that circle that he kept the intellectual proximity and friendship with Adorno that crucially distinguishes his work. A book from 1972, written with Oscar Negt under the long title of Öffentlichkeit und Erfahrung. Zur Organizationsanalyse von bürgerlicher und proletarischer Öffentlichkeit (translated into English as Public sphere and experience. Analysis of the bourgeois and proletarian public sphere), promises a bleak discourse: with a taste of the dialectic so exquisitely cultivated by Adorno’s and Horkheimer’s critical theory, it bears the evident seal of the theoretical environment from which it arose. But the Frankfurt School legacy, which Alexander Kluge always openly acknowledged, was drawn together in his work with enormous intelligence, far from the crystallizations of epigonism. The uniqueness of his work, the many dimensions of which can hardly be grasped by the canonical forms of genres, lies beyond the plurality of disciplinary and artistic fields that he has experimented with. His literary work includes narrative fiction, theory, criticism, ‘memorialistic’ writing, historical note-making and everything that a writer, a reader, a spectator and a critical observer of society, endowed with refined analytical instruments, is able to summon up. The result is an assemblage in the form of a monumental set of fragments that gradually constitute thematic constellations and invite the reader to follow sinuous, non-linear paths inside this edifice of many entrances and many exits, one that is virtually endless in itself. Similarly, his films (feature films, short films and, more recently, micro films) were made on the margins and against the standards of the film industry. His first experience in cinema was as an intern alongside Fritz Lang (to whom he was recommended by Adorno). But he would soon emancipate himself, with great conviction, from that initiation, when he directed his first short films in the early 60s. In 1962, he co-signed the famous Oberhausen Manifesto, a collective document demanding the renewal of German cinema. The renewal took place and Alexander Kluge greatly contributed to it by imposing a style of narrative fragmentation (as a filmmaker, he never wished to be the creator of cinematographic stories), inserting archive images, overlapping words and images, and employing processes that utterly disregarded the codes of cinematic fiction. He would say – and rightly so – that he is an iconoclast (adding, however: ‘a moderate iconoclast’). And when he took a long break from cinema to start his own production company and concentrate on the audiovisual for television (by providing private channels with cultural programmes which, by law, they were required to broadcast), he also revealed himself as an innovator who managed to subvert the existing television codes and concepts. The filmed dialogues (meanwhile transcribed and published in book form) with another eminent writer of German contemporary literature, his friend Heiner Müller, were hugely successful and remain exemplary works. Into these works of dialogue and cooperation (highly distinctive words in his theoretical vocabulary), he has also integrated, in various ways and on several occasions, German artists who are his contemporaries: Gerhard Richter, Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer.

The passage to literature came early, and it would be incorrect to say that Kluge has continued to follow the paths of cinema by other means. He always claimed that there is an irreducible difference between the art of images and the art of words and that he did not transition from one to the other as if he were following a continuous and direct pathway. The thousands of pages of his literary writings are made up of the widest range of subject matter in the world: history, politics, culture, contemporary literature and literature of every other period (Latin literature, and especially Ovid, holds an important place in his pantheon and his textual workshop); everything is part of that monumental symphony in several volumes called Chronicle of Feelings. Accepting the responsibility to confront himself with the German ghost of the post-war world, Alexander Kluge took on the work of the analyst and of the archaeologist who digs up what lies submerged. Almost by himself, he began the task of coming to terms with the German past. And not only the most recent past: he thought he should tell Germany’s unfortunate history, remaining true to his conviction: ‘Even at its root, German history is a laboratory of misfortune.’ But German history is not a demarcated territory within the chronicle that accompanies the course of life or of the endless stories that the history of Europe has been made up of, from Greek Antiquity to this day. Alexander Kluge sees himself as a contemporary of Ovid and makes out the Russian poet Mandelstam to be one as well. His entire oeuvre consists of the creation of chronologies that differ from those of a calendar or a linear conception of history. He establishes paradoxical synchronies and turns Marx into a contemporary of Joyce, thus taking up a film project by Eisenstein that resulted in that unique, immense film, a 570 minute long film-fleuve entitled News from Ideological Antiquity: Marx – Eisenstein – Capital (2008). To continue the work of the great authors who preceded him and produce abridgements of the great novels of Western literature: this is the task that Kluge has taken on with a critical stance towards the time in which we live, leading him to diagnose an ‘inquiétance’ of time. This odd word appears in the subtitle of the French translation of Book II of Chronicle of Feelings: ‘Inquiétance du temps’. And in Paris, where he arrived at the end of September to present this book, which had just been published in France (a publication which is not merely a translation, but rather a reconstruction of his literary oeuvre), he kept repeating the word ‘inquiétance’ with great enthusiasm (even though he always spoke in German), as if it were a concept. It was precisely on that occasion, in Paris, that this interview took place.

Share article