Objects are the material and visible incarnation of labour, and it is this that imbues them with something more: the ability to symbolise the social and economic divisions that made their creation possible. So the laptop that we use for reading and writing is not only an expression of the intelligence of the information technologists who designed it, nor the concrete materialisation of the hundreds of hours involved in its production. It represents, above all, the gulf between those who work and those who do not need to work or between those with means and those without – a class conflict, in fact. It is in its symbolic capacity, overriding all usefulness and form, that Marx finds metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties. First of all because, as he himself wrote, there is a “definite social relation between men themselves which assumes here, for them, the fantastic form of a relation between things” and “in order, therefore, to find an analogy, we must take flight into the misty realm of religion”.1 The term fetishism, which Marx used to describe this strange property of commodities, beyond their use and their market value, does in fact stem from religion: fetishes were the artefacts that the seventeenth century European colonisers thought were worshipped as if they were gods by the colonised African peoples. In this case too, human artefacts symbolically encapsulate the social relations between people, implicating them in the relations between objects or between people and objects. This theory, with which Marx basically went well beyond his economic analyses of exchange, money and production, introduces a purely symbolic element, neither economic nor material, to his description of the capitalist system. It is no coincidence that many consumption theorists inspired by Marx have speculated that our consumption of commodities relates primarily to this symbolic value: it is neither as a function of its usefulness nor simply as a function of our purchasing power (exchange value) that we acquire an object, but because of its capacity to reflect the social distinction between us and the person who produced it and others who are not in a position to acquire it. Capitalism not only involves a form of innate snobbism that leads members of different classes to reproduce their material and economic divisions in a symbolic division, but also a sort of spiritualism that turns the world of things into a mirror, a screen that reflects an abstract projection that has nothing to do with the usefulness of objects bought and sold nor with the need to exchange them. Commodities are the social “hieroglyphics”, symbols and words-in-freedom with which the society that produces them speaks about itself and its own nature, externalising in things its own internal conflicts.

Handbags, pencils, frozen food. As well as cars, shoes, chocolate and petrol. The universe of things that surrounds us seems not only to take the most disparate forms, but also has the most varied uses. One of the merits of Marx was that he showed us what unites these objects, despite their differences: the objects that surround us are, for the most part, artefacts, the embodiment of human labour, produced for the purpose of distribution, sale and consumption. They are, in fact, commodities. For Marx, unlike other proponents of classical economics, the fact of being the fruit of human labour does not determine a commodity’s capacity to embody an idea, a project, a vision. Objects are the material and visible incarnation of labour, and it is this that imbues them with something more: the ability to symbolise the social and economic divisions that made their creation possible.

"Fetishism is a sort of supra-economic or ultra-economic dimension of capitalism, a key to demonstrating that its real basis is neither material nor purely utilitarian but, just like the religion of peoples studied by anthropologists, a strange form of totemism."

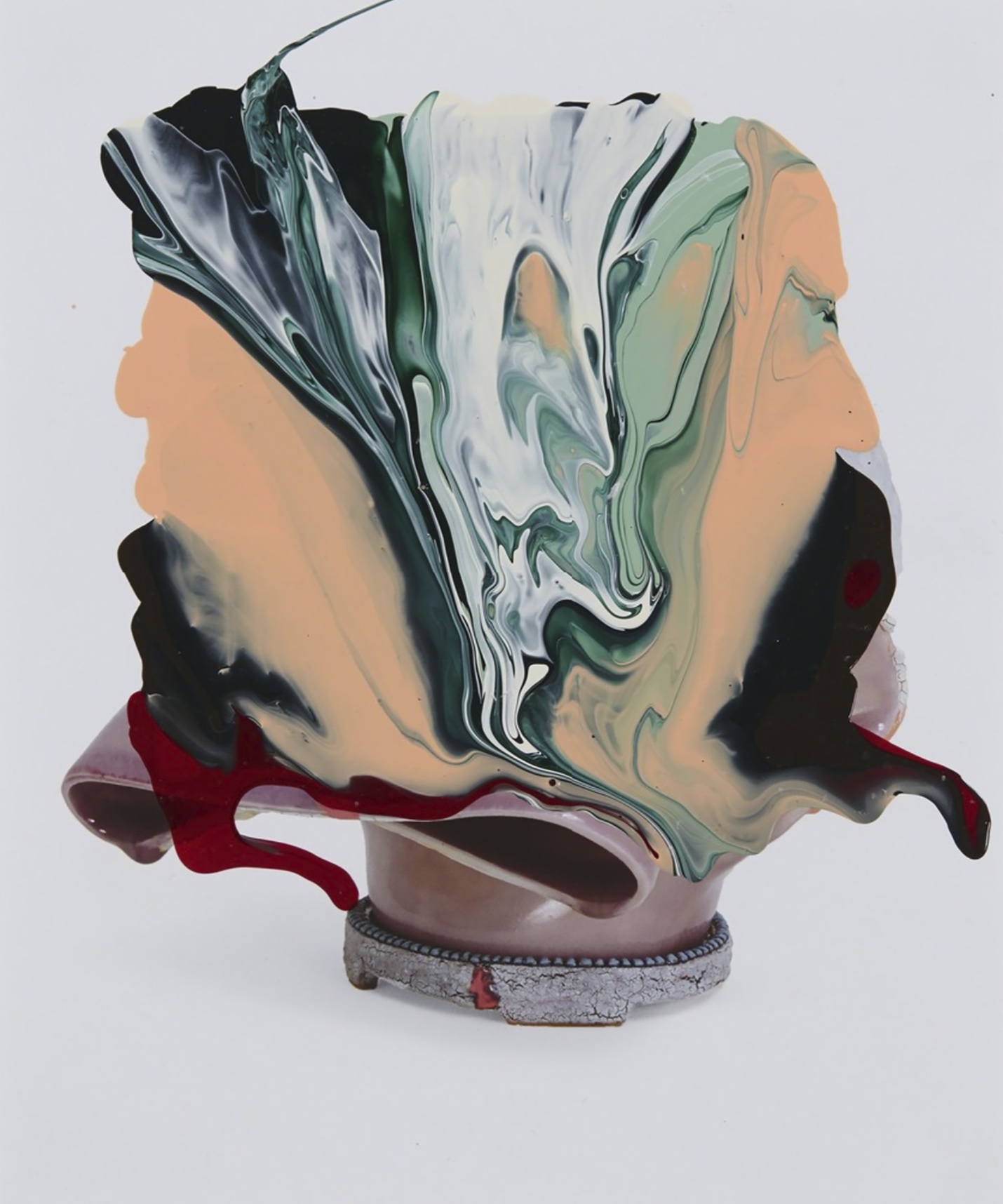

Kathy Butterly, Flee, 2016

Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

From this point of view, fetishism is a sort of supra-economic or ultra-economic dimension of capitalism, a key to demonstrating that its real basis is neither material nor purely utilitarian but, just like the religion of peoples studied by anthropologists, a strange form of totemism. Just as in primal societies, where the relations between different animal totems (eagle, bear, turtle) represent a projection screen for the reciprocal relations between the different social groups with which each of them is always associated, so it is in capitalism, where relations between the different classes are organised and played out through the reciprocal relations between different commodities (a high-performance car and an economy car, for example). The metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties contained in the fetishism of commodities allow society to be ordered and classified in the same way as the artefacts of that society are ordered and reciprocally related to each other.

There are perhaps two limits to Marxist analysis. Firstly, the view that the capacity of objects to encapsulate and express symbolic meaning beyond their usefulness and their exchange value is a theological and metaphysical dimension, that is to say, something that transcends their own nature. In reality, as many of the subsequent approaches have shown (especially those developed by Georg Simmel), all human artefacts are defined first and foremost by this symbolic capacity, which is much more fundamental and profound than any possible usefulness or exchange potential that therefore makes them true commodities. Every artefact, independently of its usefulness or its potential for exchange, represents in the first place the expression of a certain conception of the world and of society. In that sense it is wrong to talk about fetishism, because it not a matter of illusion or belief, or of a remnant of religious thinking. Things communicate and express much more than their use and value. Calling this absolutely natural and ordinary symbolic dimension 'fetishism' ultimately means to resist it, subscribing to the very utilitarianism and economism that we should fight against.

Secondly, and for this very reason, it is not solely as commodities – as objects that are produced and exchanged, and therefore as the materialisation and end result of labour – that things begin to speak, to express meanings that transcend their own social function and economic value. Things speak because the material that passes through our life cannot help but absorb the experiences, visions, thoughts and emotions that make it human. Things speak, but not only about the relations that we all maintain with the rest of society or with our neighbours. In other words, the natural symbolism of things is not fetishism because it is not only a dimension linked to the social nature of objects or human beings. If things speak, it is because every object must express the world’s view of itself, from the perspective of its own existence.

*Translated by Emma Mandley / KennisTranslations

Share article