The passageway linking the road with the little square inside the residential patio under the building where I live has, in addition to the sign that indicates its name, another life. There are often people sleeping there. They lie on sheets of cardboard, their belongings arranged at their heads and their shoes carefully lined up. The city looks on its beggars and homeless with a sense of unease. With paradoxical attitudes, perhaps. The Swedish film-maker Ruben Östlund puts it well in his 2017 film, The Square, where he interlinks this contradiction with the tribulations of the director of the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Stockholm. In the passageway, despite its tunnel-like sordidness, evening also enfolds adolescent couples as they embrace. They deserve a novel of the same name as the one Virginia Woolf gave her collection of essays, A Room of One’s Own. Two different ways of approaching the network of innocuous routines in the public sphere.

It has never been easy to turn the city into a room of one’s own. Even in 1969, the poet Anne Sexton wrote a line in her book Love Poems that confirms this, claiming we “are not permitted to kiss on the street”. It is an extraordinary line of poetry, allowing us to identify where and when it would scan well when read and capture the zeitgeist of urban thought. In Boston, Massachusetts, where Sexton lived, it obviously did scan. In other places across the world, it continues to do so. A few (but not too many) years ago, a kiss between a couple of twenty-somethings caught on the security camera of an underground station in Shanghai and published on YouTube shook the Chinese public. “In China”, wrote the journalist Jordi Pérez Colomé, “couples do not touch in public. They don’t even hold hands or give each other farewell kisses.” The ability to subvert the social order with a kiss excites us in the West. In the first decade of this century in China, the first photos of a kiss between two men and between two women, under the slightly incredulous gaze of a portrait of Mao, were released with an aura of revolution. The journalist Eugenia Mont adds that, “In the streets and parks (of Beijing), on the underground and in fast-food restaurants, it is possible to see young couples hand in hand, embracing, cuddling up together. They don’t show embarrassment at being in public places, perhaps because they have no private places.”

It is now worth asking oneself when it was that European cities started to contemplate these kisses – either with a sense of scandal or with the vague desire for the new – which suddenly started to break down the strict divisions between public and private. In Franz Hessel (1880–1941), the streets of Berlin had a magnificent navigator and mapmaker during the first decades of the 20th century. He wrote a delightful volume titled Walking in Berlin, published in 1929, which critics have always considered fieldwork for the ideas of his friend Walter Benjamin. No couple of German twenty-somethings could kiss on the streets of Berlin in Chinese style without Hessel noticing. “A Sunday in autumn. Sunset…”, Hessel writes in a description of the Tiergarten, the great park in central Berlin, “The earth breathes out a sigh of vapour, less than the open fields, more than a field of potatoes. On the many, very many benches spread out in the twilight and gloom of the winding paths, pairs of lovers sit. Some, it seems to me, are not well versed in amatory exchanges; they could learn much from a Parisian worker when it comes to caressing their dainty loved ones. Some have managed to get an entire bench for their two-person trysts, but those who are forced to double up do not seem to bother each other.” Hessel harks back to Paris as “the most carnal city ever to have existed”, in the words of one of his novels.

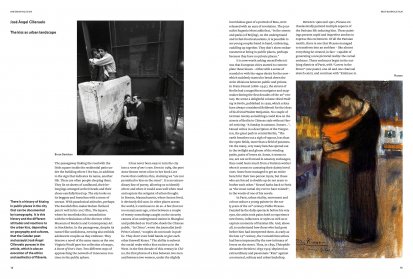

In Paris, urban vitality, movement and colour seduce a young painter in the early years of the 20th century: Pablo Picasso. Dazzled by the daily spectacle before his very eyes, the artist took pains both to experience new forms, influences or styles as well as to capture moments of Parisian life. And, above all, to understand how those who had gone before him had interpreted them. As early as the late 19th century, the Costumbrista artists had been impressed by the new intimacy of lovers on the street. Thus, in 1895, Théophile Alexandre Steinlen (1859-1923) depicted an extraordinary and passionate “Kiss” against a nocturnal, solitary and urban backdrop.

Between 1900 and 1901, Picasso enthusiastically painted multiple aspects of the Parisian life seducing him. These paintings present rapid and imperfect strokes to express this excitement. Of all the Parisian motifs, there is one that Picasso managed to transform into an emblem – like almost everything he created, in fact – capable of generating a new pictorial reality: the carnal embrace. These embraces begin in the outlying districts of Paris, with “Lovers in the Street” (one pastel, one oil and one charcoal sketch exist), and continue with “Embrace in a closed bedroom” (more intimate in appearance, although violence is present in the nocturnal light that illuminates the room, emanating from a window and the city outside the painting, unseen but perceived). This motif is returned to, in sublimated form in a fantastic pastel from the Blue Period, similarly entitled “The Embrace”, which he painted in Barcelona in 1903. But the next year, in Paris once more, Picasso’s embraces recover their violence of carnal portraiture, as evinced by a prolific series of drawings, “The Lovers”, “The Kiss”, or the countless variations of “Couple making love”. Through these works, Picasso discovers and reveals that in Paris amorous passion is a founding theme of the modern city: the intimacy attained by lovers in the street is in direct proportion to the anonymity and heterogeneity offered them by urban life. In Picasso’s Paris of the early 20th century, Anne Sexton’s line of poetry would not scan.

In a review of Walking in Berlin, Walter Benjamin made an interesting observation: “Landscape, that is what [Paris] is in fact for the passer-by. Or, to be more exact: for him [Hessel] the city presents itself in its opposing poles. It opens as a landscape and closes around him like a room.” The city of the flâneur is a landscape – according to Benjamin – which is simultaneously both external and internal. This is a core idea in Benjamin’s thinking, which he may have discovered on his visit to Naples, where he was impressed by the “porousness” of urban life. But he developed it in his study of the Paris of Baudelaire: “The street becomes a living space for the flâneur, who finds himself as at home between the façades of the buildings as the citizen does inside his own four walls.”

Architecture and urban planning at the outset of the 20th century were about to decree (at least as a utopia) an end to the division between what is inside and what is outside. The inside and outside of a building, with architectural rationalism’s new iron and glass structures, ceased to be immoveable concepts. The German Pavilion in Barcelona designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich may stand as the paradigm of this meeting between spheres.

Share article