February 1

In the diary written by the New York gallerist Ted Bonin for Electra, personal time and world time cling to each other in an endless embrace. In the days recorded, presence is a machine of absences. Here, what is found comes with what has been lost: artworks bring faces and faces bring deaths. Through these words, which sadden and cheer, travel the questions time asks art and life. Days crossed by the light and shadows of a city where nothing stops. At the end, an unpronounced name – and silence is the voice of a threat.

Paul Thek, Portrait of Peter Hujar, ca. 1963

© Photo: D. James Dee / Estate of George Paul Thek / Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life opens at the Morgan Library & Museum. The intimacy of Hujar’s portraits was often born of a relationship or attraction. My path to Peter’s work was through the work of one of his former partners: Paul Thek. I began working with Thek in 1988, which unfortunately turned out to be the last year of his life. Hujar and Thek’s relationship began in Miami in the late 1950s and continued, in varied form, over the decades. After Paul’s death, I was periodically offered works for sale by his friends and acquaintances; Thek gave and bartered his art throughout his life. Frequently I was told that the friend of Paul’s was also a friend of Peter’s and that they had a Hujar work too. The circles of coincidence, or fate, continued with Stephen Koch calling me to say that a painting of Peter by Paul was in David Wojnarowicz’s loft and that David wanted it picked up as he’d be leaving soon. Hujar’s will stated that the art he owned on his passing was to be returned to its maker. Portrait of Peter Hujar travelled through the three artists and by the winter of 2018, it is like the central ring of a tree trunk that is having a growth spurt.

I’m invited to the Morgan Library opening by Elisabeth Sussman, whose exhibitions of Eva Hesse, Diane Arbus, Gordon Matta-Clark, and Paul Thek would have been joined by a Hujar retrospective—but institutions do not always see as clearly as curators. We meet for a drink beforehand at The Langham, a hotel, equidistant between the Morgan Library and the Empire State Building. A pair of large and stunning Alex Katz figure paintings are behind the reception desk; the receptionists and concierge echo Alex’s painted images. Upstairs the bar is swanky, pricey, and just the right place to have a drink before a one-block walk to the Morgan. When we arrive, the opening is well under way and at every step there is a friend, a friend of Elisabeth’s, a friend of Peter’s, or a friend of Paul’s. The exhibition includes the full range of Hujar’s subjects and represents his penchant for mixing dissimilar photographs. The title, Speed of Life, evokes the conundrum of viewing Hujar’s uncanny images. We want to hold on to each image, grasp its essence, and feel its every precious tone before we move on. The narrative of his life blends with ours and it is all going too fast but it’s wonderfully full. Hujar’s photographs epitomize the raw edge of downtown alternative culture and no one who has followed his work would have imagined that its ultimate presentation would be held in a library known for its shows of fine etchings by Old Masters and medieval manuscripts. Hujar’s archives have been donated to the Morgan and will forever live with the letters of Jane Austen and the journals of Henry David Thoreau.

February 8

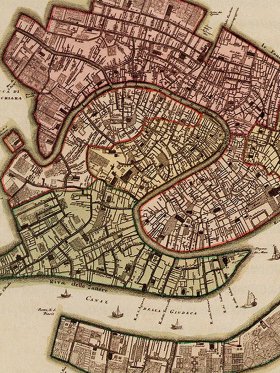

Tonight, Danh Vo’s Take My Breath Away will open at the Guggenheim. It is preceded by a brilliantly revealing profile in The New Yorker by Calvin Tomkins. One of Vo’s talents is his insight into other artists’ work and his thirst to both own and share those works. In 2015 this aspect of his practice was accorded the run of the Punta della Dogana, Venice, for the exhibition Slip of the Tongue, which included several artists that form Vo’s core circle: Julie Ault, Peter Hujar, Nancy Spero, Paul Thek, David Wojnarowicz, and Martin Wong. Except for Ault, a close friend and collaborator, none are living but all feel fully present in his world. The Guggenheim opening is one week after the Morgan opening and the plangent horn of Hujar’s Portraits in Life and Death (1976) sounds at the back of my skull as I enter the exhibition.

The show is both beautiful and disorienting, especially at this evening opening; it’s also huge, filling the entire rotunda of the Guggenheim. I take the tiny half-oval elevator to the top and see Vo’s show as I descend Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiral. Alluring shipping cartons whose logos (Budweiser, Coca-Cola, Corona, etc.) have been gold leafed, punctuate an array of aesthetically challenging “abject” works such as a skinned leather chair previously owned by Robert S. McNamara and purchased at auction by Vo. After two ramps, as I approach a pair of We the People gold leaf “paintings”, the guard standing nearby says, “The pretty Statue of Liberty paintings are over here.” I reach the bottom and am happy to see familiar faces. Tim Rollins’ recent death is an unavoidable thought as we greet each other. It’s acknowledged and then put aside to focus on Vo’s triumph. I wish the opening was smaller, but it’s big and swirly and I don’t stay long.

February 9

A presentation for Julie Ault’s new book, In Part, a collection of selected writings from 1980 to the present, is held at Galerie Buchholz in the midst of a related group exhibition. The gallery originated in Cologne and is the collaboration of Daniel Buchholz and Christopher Müller. The gallery is known for unusually thoughtful exhibitions, such as the Raymond Roussel themed The President of the Republic of Dreams, and for its singular location, half a block from the front door of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ault’s fascinations are wonderfully diverse and her practice as an artist is most frequently expressed in the medium of exhibitions and publications. A founding member of Group Material, Ault’s work examines the overlaps of politics and aesthetics.

The only image in the book is its gorgeous cover photo by Heinz Peter Knes—a tangle of branches and the nucleus of a budding flower. The tangle references Ault’s idea that no matter how prolonged and extensive an exploration of a subject or engagement with an archive, an authoritative text is never an accurate representation. The introduction to In Part is written by the esteemed critic and curator Lucy Lippard whose interests, political awareness, and collaborative spirit are a historical parallel for Ault. Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 is a key text for Ault and one feels both a mirroring and a furthering of Lippard’s essential document and practice in this new publication. In Part beautifully and humbly represents nearly 40 years of writing, beginning with a Group Material statement and ending with a soon-to-be published text on David Wojnarowicz. During the book presentation with Moira Davey, Ault humorously summarizes the look of In Part as, “If you saw it in a bookstore, you’d think, ‘Oh my God, did she die?’” The guests at tonight’s presentation include several of Ault’s fellow artists and collaborators although sadly Tim Rollins has unexpectedly passed away since the book’s publication. For more than thirty years, Rollins rewrote the meanings of collaboration and education in his work with K.O.S (Kids of Survival) in the South Bronx. Rollins reportedly told his students on the first day of class, “Today we are going to make art, but we are also going to make history.”

Car services have been on the rise for some years and Via has set itself apart by using software that calculates both pickup and drop off locations when “pooling” riders. I’ve thrice been in a car with a friend and colleague. We live in the same part of the city, but only see one another at openings or art fairs. Now we are neighbors who can talk about the weather or current events on our morning commutes. I don’t often go to the Upper East Side, but by chance I now have a Via pal who shares my route across Central Park. The first time we shared a car was on the day of the Women’s March, on the anniversary of Trump’s inauguration. Born out of protest and solidarity, it puts a demonstration of the power of women together with the anniversary of an egregious event. Happily, our second cross Central Park ride was after Julie’s book party. One cannot plan these shared rides—it is the result of shared habits and happenstance.

February 13

Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald’s portraits of Barack Obama and Michelle Obama are unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. The choice of contemporary artists, both known for portraits, but not commissions, is as fresh and hip a choice as a first family can make. The Obamas lived with contemporary art during their eight years in Camelot II and they are to be commended for infiltrating the National Portrait Gallery with fresh talent and attitude.

Wiley initially gained acclaim for his portraits of ubermasculine black men, provocatively posed with the signifiers of aristocracy (thoroughbred horses, royal armor), all set against dense, colorful patterning. The headier qualities of Wiley’s work somehow remain on the downlow and I wonder which elements of Wiley’s canny casting Obama perceives when looking at his work.

Amy Sherald’s portrait was immediately criticized for not resembling Michelle Obama, with detractors going so far as to claim that the artist had painted “someone else.” Sherald paints her subjects’ skin in gray tone; the result of this grisaille is that they are first and foremost human. America’s much revered and missed former First Lady is portrayed as the beautiful princess of dreams past and something we long for, at this moment, for our future.

February 14

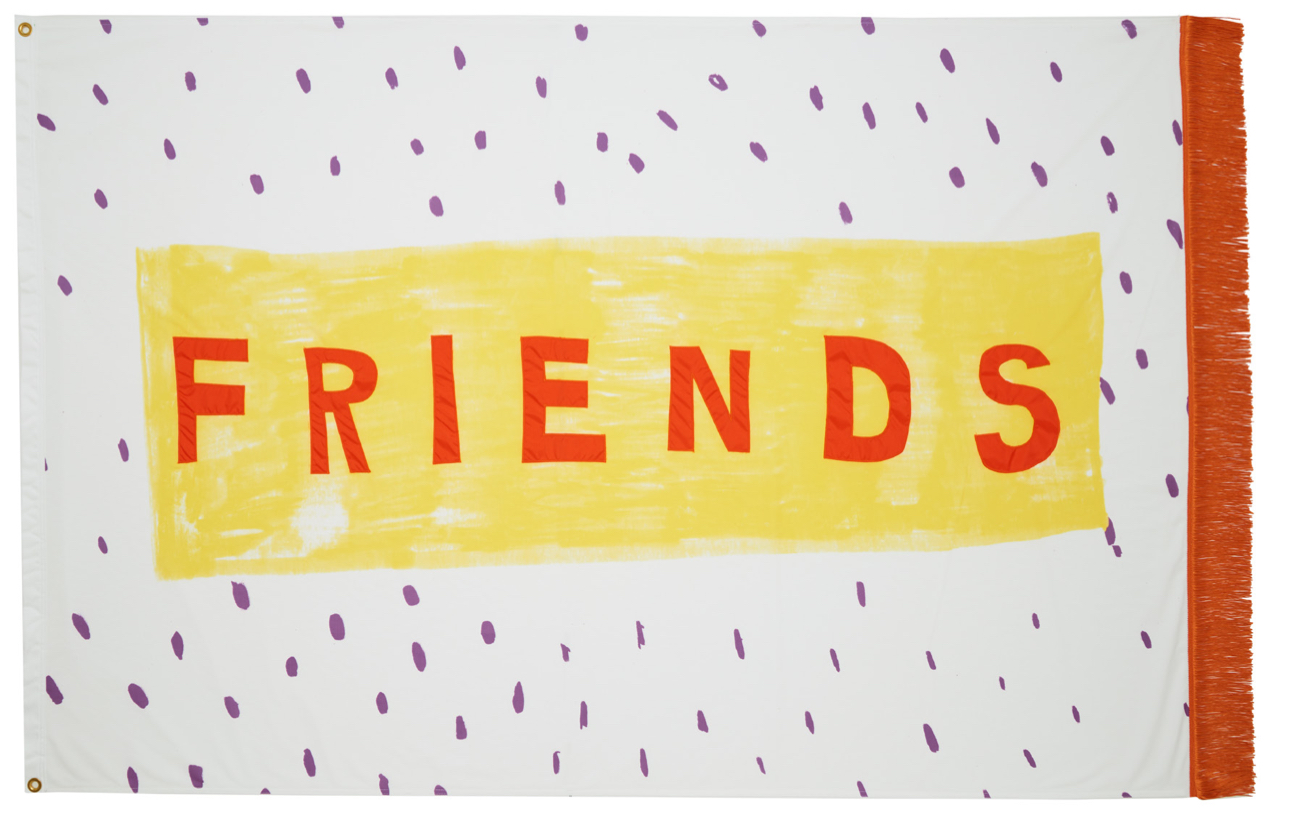

Although we’ve not met, I’ve crossed paths with Alex Da Corte twice through his interest in two artists whose estates I have long represented. The first time was when he made a “dedication monument” to Paul Thek for the exhibition First Among Equals at the ICA, Philadelphia, in 2012. More recently, for Creative Time’s Pledges of Allegiance, Da Corte created a flag based on a notebook drawing by Ree Morton for her 1975 public art project Something in the Wind. For that work, Morton made flags for approximately 100 friends, each embroidered with their first name and a symbol. After a week-long installation on the masts of a ship at the South Street Seaport, Morton periodically installed the flags in various exhibitions or events, while also gifting them to the friends named on the flags. Forty years later, Da Corte’s Friends (for Ree) is installed in sixteen locations across the United States.

Alex Da Corte, Friends (for Ree), 2017

© Photo: Nicholas Prakas / Cortesia Creative Time

February 17

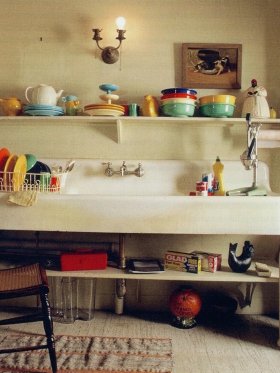

C-A-T Spells Murder, an exhibition of new work by Da Corte, opens at Karma Gallery on East 2nd Street. It is snowing heavily and that makes the entry into Karma’s orange carpeted space all the more surreal. Neon “storefront windows,” which could easily be on the same city block, hang on the walls, leading to a video projection featuring a woman whose face is obscured by a rack of pool balls, each emblazoned with an ambiguous icon. A book of spooky stories accompanies the exhibition. Much to unpack.

February 20

I return to the Upper East Side for a morning look at Vo’s Take My Breath Away. The museum opens at 10 am but I’m so early that I’m waiting for the museum bookstore to open at 9:30 to get indoors. Winter is abating for a day with temperatures predicted to be in the low 60s. It’s not quite warm—it’s more blustery and fresh. Each day of the past year I awake hoping a strong wind will blow away the nightmare of our current administration and, as I sit outside the Guggenheim, it fleetingly feels like a possibility. Today, natural light is pulling its weight to fill out the bays and ramps of this spare installation. Only a few dozen visitors are in the museum at this early hour. Archive of Dr. Joseph M. Carrier 1962-1973 (2010) looks especially strong. Like many of Vo’s works it’s a presentation of existing materials but here a sense of the artist as a person is more evident. This work coyly switches between the representor and the represented and it’s exquisitely displayed in small, illuminated, stage-like boxes, sunk into the Guggenheim’s walls. The quieter pace of a morning visit allows for the attention Vo’s show needs. Faded velvet hangings from the Vatican’s storage of holy forms, Talavera pots depicting atrocities but holding new greenery, and displaced and deconstructed crystal chandeliers all sing.

After the Guggenheim, I return to Buchholz as the crowds at Ault’s book party didn’t allow for a look at the exhibition, whose biggest payoff is the four-meter-wide David Wojnarowicz painting Earth, Wind, Fire, and Water, which has seldom been seen since it was painted in 1986. It is one of Wojnarowicz’s largest and most accomplished works and it is wonderful to see it looking so strong thirty years later. The Whitney will mount History Keeps Me Awake at Night in July of this year, bringing yet another member of our lost society to greater prominence. The list is getting long: Thek, Hujar, Wong, Wojnarowicz. What is it about 2018 that has brought these artists such attention, according them a status previously denied?

I’ve been receiving the New York Times via email for more than ten years. I’m not sure how it started, but presumably it was an exploratory program to test-market digital subscriptions. At first, I missed the physical newspaper for its tactile qualities and completeness, but now I appreciate the brevity of exposure to the endless chain of sad horrors emanating from our nation’s capital. Today, more than half of the stories concern someone whose name I vow I will never utter again.

Share article