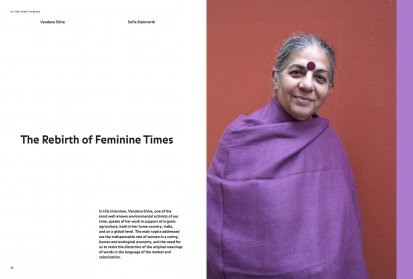

With an immense social and political impact and world-wide recognition of the work she has carried out in defence of organic agriculture, she might well be the most well-known environmental activist of our times. Throughout the past decades, Vandana Shiva has stood out for her unshakeable commitment against GMOs (genetically modified organisms) and the implementation of chemicals in agriculture, which has led her to face some of the most powerful multinational companies of our times – among them Monsanto, Cargill and Bayer – with incomparable courage. Central to her work is the idea of seed freedom. The two core elements that stand behind this belief are nature’s right to develop in its own ways and a farmer’s right to breed seed independently of big corporations’ GMOs and chemicals. Her fight is one against ‘biopiracy’: a term with which she addresses the ambition of corporations to claim patents on seeds and, in consequence, as Shiva argues, on life.

She is active in teaching and public speaking, as well as advising governments and NGO’s on issues related to organic farming. Her focus lies in the preservation of indigenous knowledge, the promotion and conservation of native seeds, and fair trade. With a firm anti-globalization philosophy, her engagement on behalf of the environment and food sovereignty takes on various forms and goes from publishing (her list of publications already counts more than twenty books) to the creation of seed banks through her organization Navdanya in her homeland, India. Through its direct political engagement, Navdanya was among the three bodies that, in 2000, won a long battle in the European Patent Office against the biopiracy of neem (a tree native to the Indian subcontinent and the source of neem oil) by the US Department of Agriculture and the corporation WR Grace. Other achievements were to follow, with a patent claim on Basmati rice by an American company called RiceTec in 2001 and the revoking of Monsanto’s patent on an Indian wheat variety called ‘Nap Hal’.

Acknowledging the global nature of environmental issues and the need for cooperation to respond to our present challenges, one of her in the first person main objectives is the creation of networks that connect smaller environmental movements from all over the world – a task she is accomplishing through the Seed Freedom platform and the organization of the yearly BHOOMI Earth Festival.

Furthermore, Shiva’s work shows a strong connection with women and feminism. Her first book, Staying Alive (1988) examines the marginalization of women in relation to the violation of nature in the Third World and paved the way for her life-long engagement with women’s rights and knowledge. This publication was followed by a report for the FAO (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization) on Women and Agriculture, which was entitled Most Farmers in India are Women. Further inquiring into the crucial relationship between women and the environment, she is the co-author of Ecofeminism (1993), along with the German sociologist Maria Mies. This publication is acknowledged as one of the leading theoretical discussions that address the system of the domination and exploitation of both nature and women through the hegemonic forces of capitalism and patriarchy.

In this interview, Vandana Shiva told us about the main concerns that guide her and how her life experiences have led her to become the activist she is today.

Share article