May 1st is not a holiday in New York or the US, despite the fact that the date began by memorializing a US event: in Chicago, 1886, a 400,000 person strike in favor of the eight-hour work day resulted in a riot after a dynamite bomb was thrown at the police.

May 1st wasn’t a holiday this year either. Yet, this year, there was an effort to signal the date amidst the biggest increase in unemployment since the Great Depression and a car caravan crawled the boroughs.1 It also marked the second month of a rent strike and a larger movement to freeze rent payments without legal consequences for the tenants, after it became clear that the initially hopeful promise of an eviction and mortgage moratorium by Cuomo was going to stop at just that.

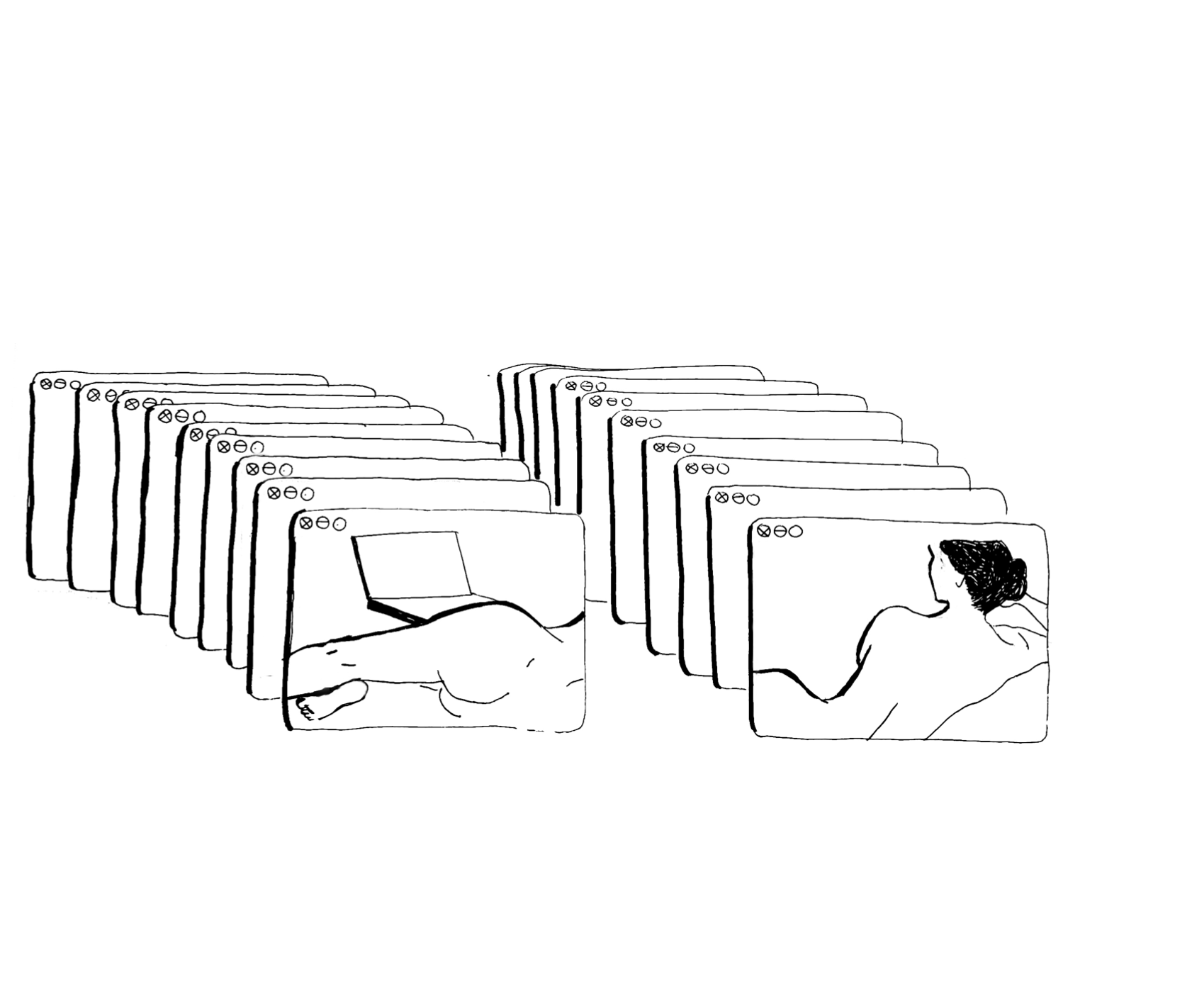

The difficulty of adapting forms of protest during a pandemic made me try to remember a tweet earlier in March that I forgot to screenshot. Roughly, its point was: during quarantine those who leave the house to work define what jobs the economy should always have valued. During a pandemic – contrary to an economic crisis – what comes to the fore about essential work is just how much of it is what feminists have termed social reproductive work: traditionally unwaged or low-waged work of care. Care considered in a broad sense, as work traditionally performed by women – be it affective or material. Social reproduction extends to institutions, be they public, private, community or state-led, that perpetuate life.2 If disaster capitalism has allowed for economic restructuring in the last five decades, during a pandemic, the social reproduction disaster it went hand-in-hand with is now painfully visible. Quarantine proves that any essential worker has always been a de facto member of the working class. And yet this statement stands in contrast to the rapidly rising notion of the working class celebrated in the first Mayday holiday that commemorated the events of Chicago’s Haymarket, around 1890. Back then, labor struggles presented as mostly male and industrial.

***

One in three jobs currently considered essential in the US are held by women and a majority of these by nonwhite people.3

In health care, four out of five jobs are held by women. This pandemic, which brought the world to its knees, has made a more long-standing global crisis apparent: the crisis of care. Sociologist Nancy Fraser’s use of the term predates this pandemic by several years. Fraser’s text “Contradictions of Capital and Care” attempted to characterize the particular form of structural contradictions that liberal capitalism has placed on social reproduction in the Global North since the 19th century: by separating social reproduction from economic production, and concealing the former’s importance and value; and then presenting economic production as a self-sustainable job market or labor force.4 This crisis of care alerts us to the cyclically compounding effects of economic production’s “drive to unlimited accumulation [that] threaten[s] to destabilize the very reproductive processes and capacities that capital – and the rest of us – need.”5 Fraser’s was an attempt to signal how the systemic undermining of care work could implode the global market, as much as any economic or environmental crisis could. That much seems obvious now.

Social reproduction itself looked very different when the original events of May 1st took place: according to Fraser, liberalism was then consolidating its social reproduction into the private sphere of the household. The bourgeoisie did so historically by exploiting low-waged servants or slaves. Workers’ movement struggles at the turn of the 20th century aspired to this gendered division of labor: men fought to increase their wages so women could stay at home, unwaged. In both instances, these domestic forms of social reproduction became moralized as love and virtue. This laid the groundwork for the nuclear family to emerge.

[...]

Share article