Thomas Carlyle, the 19th century British historian, once said, ‘History is but the biography of great men.’

Wrong! Great women also make history. So do other impersonal factors: social movements, economic conditions, international developments, ideas and institutions. But some individual political leaders have a decisive impact on history and their biographies shape the impact they have.

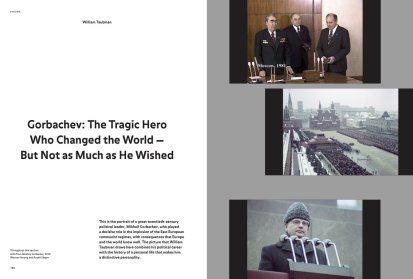

One such leader was Mikhail Gorbachev. He helped to destroy Soviet totalitarianism. More than anyone else he helped to end the Cold War. He sought to reform and preserve the USSR, but he ended up contributing unintentionally to its collapse, leaving him a president without a country.

His great power as a Soviet leader enabled him to transform his country. His uniqueness – the way he differed from other Soviet leaders – suggest that his character and personality are central to understanding what he did with his power.

As leader of a non-democratic regime, he was not constrained by a free press, by powerful interest groups, by constitutional norms, or by the rule of law. If he had acted as other Soviet leaders would have in his place, we might say that he was motivated by values that they all shared, or that he responded as most of them would have to the dictates of the situation they all faced. But Gorbachev was unique. When he took power in March 1985, most of his Kremlin colleagues wanted minimal reforms for their country. But Gorbachev tried to fully democratize it. Toward the end of his time in power, he was supported by only a small minority of the Kremlin leadership: Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze, Gorbachev’s chief ally Aleksandr Yakovlev, and Vadim Medvedev. Moreover, none of these three was a truly independent actor; the only reason they were in a position to support Gorbachev was that he had either appointed them to the Communist party Politburo or kept them on.

The late Russian scholar Dmitry Furman framed Gorbachev’s uniqueness more broadly: he was ‘the only politician in Russian history who, having full power in his hands, voluntarily opted to limit it and even risk losing it, in the name of principled moral values.’ For Gorbachev to have resorted to force and violence to hold onto power would have been ‘a defeat.’ In the light of Gorbachev’s principles, Furman continued, ‘his final defeat was a victory’ – although, one must add, it certainly didn’t feel that way to Gorbachev at the time.

Given his unique impact not only on his country, but on the world, we must try to answer such key questions as: How did Gorbachev, who once wrote a high school essay praising Stalin to the skies, become ‘Gorbachev,’ the grave-digger of the Soviet system? Why did the Soviet regime opt to make such a man its leader? Why did he attempt to democratize the USSR and why did he fail fully to do so? How did Gorbachev, the Soviet Communist leader, and Ronald Reagan, the arch-conservative American president, become almost perfect partners in ending the Cold War? Why did Gorbachev allow the Soviet Union’s East European empire to break away without firing a shot to prevent that?

All these questions have complicated answers involving many of the impersonal forces I mentioned at the start of this essay. But I will focus on his biography.

Born in 1931, Gorbachev grew up in terrible times. Two of his uncles and one aunt starved to death in the terrible famine of 1932-1933. Stalinist purges of the 1930’s swept both his grandfathers into the Gulag, his mother’s father arrested in 1934, his other grandfather in 1937. The Nazis occupied Gorbachev’s rural village for several months in 1942. Famine struck again in 1944 and 1946.

Yet Gorbachev emerged as a remarkably optimistic person, full of self-esteem, extremely confident and trusting in his fellow citizens, all qualities that later shaped his career as a political leader. It took an extremely optimistic and self-confident leader to try to democratize a country that had never known democracy – and a leader who trusted his fellow citizens to govern themselves.

Share article