The fingers are those of women in the Paris metro, who have set out purposefully from home early in the morning; the trouser flies are those of men ‘brutally ripped from sleep’, as Louis Aragon writes, who stand in the metro before their day is hijacked by work, and there ‘become conscious of their bodies again’. For the women, the promise of an affair, or perhaps just a furtive pleasure, briefly snatches them from the morality that makes their daily lives so dreary. The man who tells of having been their bedazzled prey admires ‘the courage of their attack’. Happy are the men who have been approached by such liberated women, among the indifferent crowd and despite the jolting of the carriage! In the pages that follow, Aragon goes on to describe these encounters: how one woman, when he was expecting a caress, instead seized him forcefully, or how, when he was pressed up against the back of another, she spread her buttocks under the pretext of keeping her balance as the train rattled along, so that she was better able to move up and down against his penis. The introduction of the first metro lines coincided with the beginning of the women’s emancipation movement.

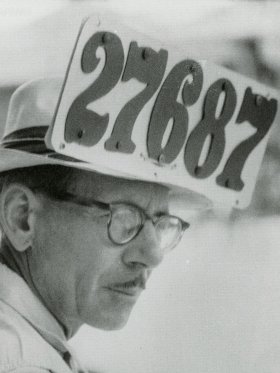

This account, written at the end of the 1920s, forms part – under the title L’Instant – of a work called La Défense de l’infini [The Defence of the Infinite]. Aragon burnt the manuscript under the eyes of his mistress at the time, the very independent Nancy Cunard, who had many lovers. Nancy left Louis shortly afterwards. Some extracts from the book that had already been published, together with some texts published anonymously, such as Le Con d’Irène [Irene’s Cunt], and other unpublished texts that had been discovered, were published in 1986, after the writer’s death, with the title La Défense de l’infini (fragments). The book contains pages in which the clarity of the vision and the beauty of the language bring the power of pornography to a climax. I cannot read them without feeling their urgent call at the pit of my belly.

I am a shy woman and was even more so when I was younger. I was embarrassed by men looking at me – not that I was afraid of what it implied, or ashamed of what it might imply about me, but rather because it made me think about my body, which I thought of as awkward, and because this thought was weighed down by a jumble of narcissistic anxieties. That is why I fell to using hand gestures a lot, probably to hide my body behind them. But I have never dared to take the initiative with my hands in the metro, though I have travelled on it every day, ever since I had to earn my own living, so since I was eighteen. Of course, there were times when I let things happen, when it was done gently. Once, on my doorstep, I kissed a man who had followed me right into the street; he was not seeking anything more and he went off happy. I recoiled only once, but that was on the bus, on a day of strikes: travel problems had made me very late and I had an appointment with my psychoanalyst. It is true that this happened at a different time to that described by Aragon: nobody believed any more in virtue or chastity, people were living together without getting married, or divorcing when they no longer loved one another, no one believed in God anymore and, as for the police, we were throwing cobblestones at them. I made love with many of my friends, as and when I wanted.

However, all my life I have had the fantasy of a fluid, fragile desire pervading the urban atmosphere, with a softening effect on the behaviour of people who are usually hurried, harried and repressed. Caressing a hand that holds open a door for you, feeling another hand sliding up your legs as you expose them to the person behind you on the escalator. A pressure or a knowing smile that holds you to nothing when you have to slip out of the metro’s mass of humanity in the rush hour. All this, just in passing, without any fuss. Gestures and looks that would fill the air between each of us and everyone else with a sort of fluffy substance that would soften flesh, disarm the most hostile and win over the most hard-bitten. Sadly, in today’s metro, a vast space has opened up between men and women who are only interested in jabbing at their phones.

*Translated by Emma Mandley / Kennistranslations

Share article