It was in Venice, when clocks silence the hours and lions dance an invisible, flying ballet. This dream city seemed to exist just to provide her with a place that her fevered imagination could accept and recognise as her own.

In the hot, languid summer nights, her tall slim figure could be seen strolling under the arcades of St Mark’s Square. Her hair was a blazing colour, her eyes were painted, shadowed and lined Egyptian-style with kohl. Her pupils were huge, dilated and sparkling from drops of belladonna. Her skin was powdered white to create an other-worldly look. She was naked except for a majestic cape of velvet or fur and her hands clutched long leashes trailing two spotted cheetahs. Or sometimes there were two equally spotted Dalmatians.

Sometimes, she swapped her diamond, ruby, sapphire or emerald necklaces that sparkled briefly in the indigo dark of night for a cold-scaled snake that she wrapped round her neck like a lost soul from another kingdom. Behind her, a huge Nubian servant lit her steps with a twelve-candle candelabrum. Her eyes did not see what they were looking at but looked at what they saw – a vision that expanded, spread out, elevated, changed, warned and alarmed everything. There are people who have the power to give reality the form of their own ghosts, fantasies, dreams, illusions, chimeras and obsessions. They have the gift of bestowing a kind of reality on their reveries, deliriums, desires, imaginings, hallucinations and fictions. In this passage from one world to another, which is one of the most dangerous and disfavoured by the gods, a person risks what they are and what they have.

There are people who have the power to give reality the form of their own ghosts, fantasies, dreams, illusions, chimeras and obsessions. They have the gift of bestowing a kind of reality on their reveries, deliriums, desires, imaginings, hallucinations and fictions. In this passage from one world to another, which is one of the most dangerous and disfavoured by the gods, a person risks what they are and what they have.

The nobility of this ancestral dynasty is peopled by exiled gods like Vulcan, banished men like Adam, crowned anarchists like Elagabalus, martyred geniuses like Giordano Bruno, murderous aristocrats like Elisabeth Báthory, victimised executioners like the Marquis de Sade, overthrown monarchs like Ludwig II of Bavaria, fugitive empresses like Elisabeth of Austria (Sisi), disgraced dandies like Oscar Wilde, imprisoned artists like Artaud, criminal saints like Genet, failed condottieri like Mishima, murdered magicians like Houdini, tortured Venuses like Anaïs Nin and ruined heretics like Pasolini.

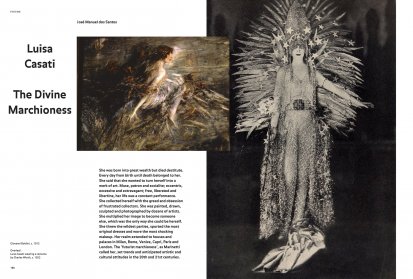

Marchesa Luisa Casati belongs by mythological lineage and natural right to this strange, tireless genealogy of those who made their lives a destiny and a mess. She was one of those tragic heroines that live their lives at their own risk and become the work of art that they themselves have painted and the book that they have written.

La Casati, as she was known, accepted nothing as it was given to her. She raised the lightness of a castle onto the stationary weight of a hill. She unleashed a fast, intent river onto rocky, apathetic land. She spread her wings for a breathtaking flight on the vertex of a violent wind. She turned the world into fiction and reality into a spectre. She volatised matter, transubstantiated nature and sublimated the body. For her, living was transgressing. More than that, it was transfiguring. Better still, it was transmigrating.

She was one of the richest women of her time and at the end one of the poorest. She lived in splendour and then in penury. She was a millionaire and a pauper, blessed and cursed, a muse and a martyr, and a patron and a beggar. Everything that she touched took on her gravelly voice, the insolent colour of her eyes and the long lasciviousness of her gestures.

Share article