Magali Reus is mostly known for her shape-shifting sculpture. One representative work, Dearest (Alibi), 2018 – first presented as part of the recent Hepworth Prize exhibition, for which Reus was nominated – epitomizes her combinatory approach to object- ‑making. A series of aluminum and steel brackets and braces clings to the wall of the gallery; from it, armatures extend outward, into space, one holding a cowboy hat, another a sliced oil canister, and still another a dark blue triangular object that bears some resemblance to a warning triangle. Parts of the sculpture, and the series to which it belongs, are recognizable as things-from-the-world, others just barely so. Is that a bicycle seat? A boot? As with much of her work, Dearest (Alibi) presents a visual system that deconstructs objects and images in a post-Fordist détournement of factory systems.

Born in The Hague, Netherlands in 1981, Reus has lived and worked in London for nearly two decades. Her early work established her practice as one of subtle incisions and deconstructions, often of simple objects and object systems. A 2014 exhibition, In Lukes and Dregs, at The Approach in London included several large and small fridge-like structures (what the gallery referred to as “cheapskate architecture” in its press release) containing netting, burnt pizza, and cutlery. None of these objects were “real,” of course, that is, they were not made of dough or the usual materials. They had not been found, per se. Rather, they were produced by other means, using steel, rubber and foam – simulations of the familiar, domestic world that interred their cribbed referents in a near monochromatic dreamscape. Later work advanced Reus’s sly interventions into our expectations as to what an object is (and what it can do) in order to suggest that more complex operations of meaning are at work under that object than might meet the eye. In her 2015 series, Leaves, for example, large-scale locks are cut to reveal mechanisms just beneath the surface of the object.

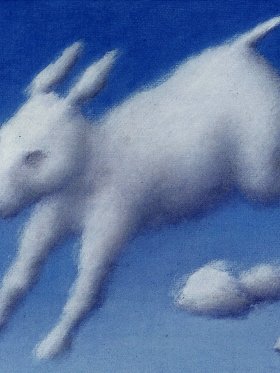

I first encountered Reus’s work in 2016, when she invited me to her East London studio to see the mock-ups for a series of sculptures that reference riding saddles, which were shown at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam in 2017. These works layered fabrics, leather, and synthetic materials into gorgeous objects that suggested both rider and horse but could not, in their complexity, have been used by either. I contributed a short story to the catalogue for the exhibition titled “Discipline Among Horses.” In it, I imagined the different voices of the speculative riders who might, in some harried future or unfamiliar past, have used these saddles to ride into the sunset. One voice imagines the Italian actor Monica Vitti riding the saddle-as-Ducati motorcycle (from the 1975 film Blonde in Black Leather), another calls the unseen horses “great semis of flesh & blood & bone.” I have always seen Reus’s work as both an art of possible and impossible objects for possible and impossible places and people, drawing, in her multitudinous way, on multiple landscapes of meaning and potentiality, all the while defying genre and categorization.

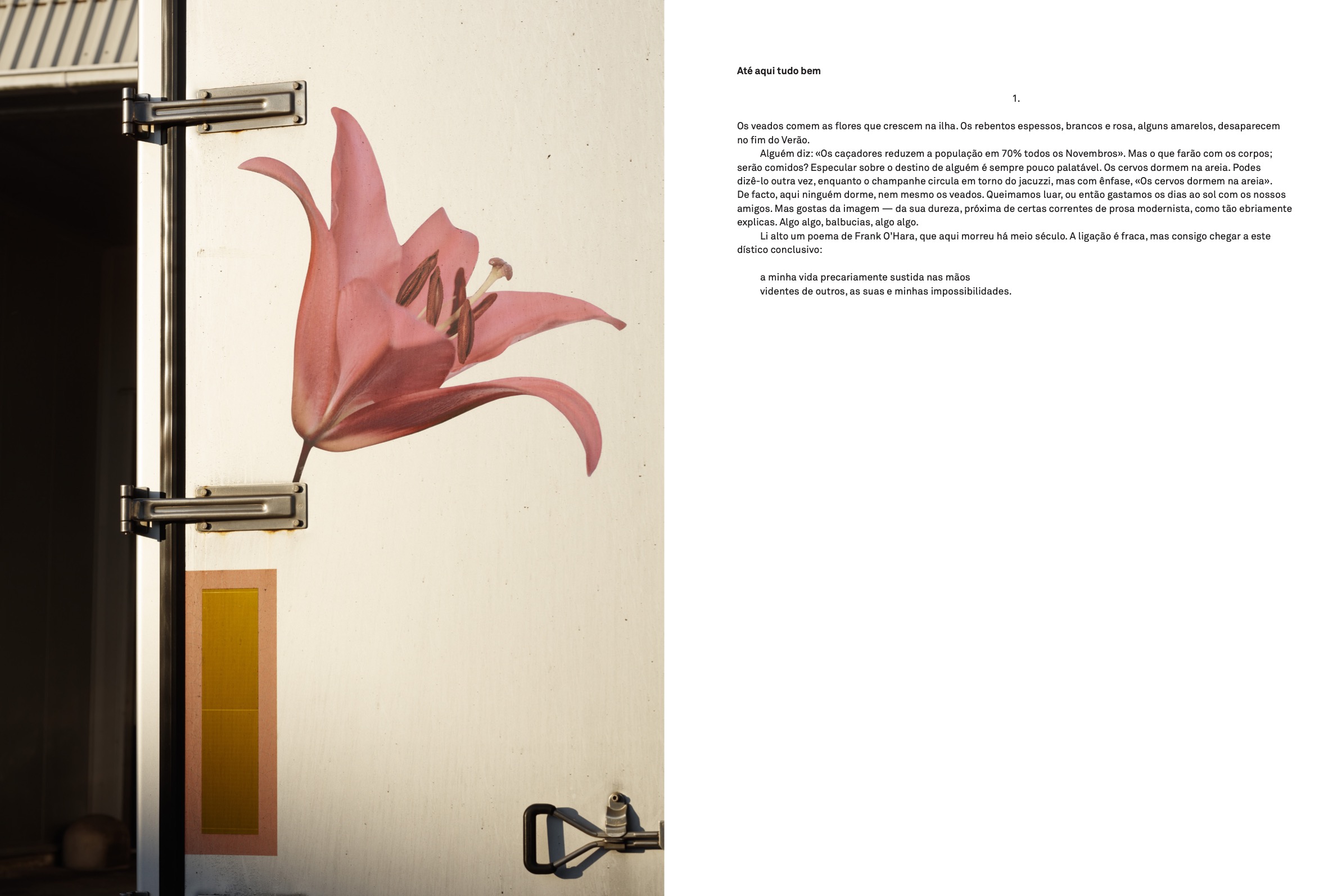

The following portfolio, specially commissioned for this magazine, consists of photographs of flowers and flower delivery trucks. It is the first time the artist has presented her photography. Alongside these images of trucks, their sides printed with decals of flowers, Magali shot wild flowers in situ against a white backdrop or alongside road signs in the summer. They have an eerie, frozen beauty. Like trucks, flowers are essentially vehicles for transport and production, their pristine aesthetic appearances masking a singular functionality – to reproduce, again and again, as far and as wide as their species allows them. Trucks obey a similar, economic logic, howbeit with considerably less flourish; they too go as far as their product takes them. In this, the trucks and flowers recall much of Reus’s sculpture, which always seems fascinated by the potential for one object to mock, or copy, another – and to extend, in the copying, the conceptual remit of the otherwise mundane.

[...]

Andrew Durbin

Share article