Certain dates – shockingly recent – help to position women in the narratives of history and the history of art: 1792, the year when the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen1 was rejected by the French Convention nationale; and 1897, the year when women were first accepted on the official courses of L’École des Beaux-Arts. Even if it is impossible to recover the many centuries of silencing, it is imperative to voice our awareness of it.

For this reason, it is ill-considered to dismiss as fashionable the regularity (and doggedness) with which museums now cram their programmes with women’s shows and events, especially when they echo serious and coherent research and are presented as part of a programme of redress. Among others, this is the case of the most recent calendar of events at the Centre Pompidou and Musée d’Orsay in Paris.2 Both museums have refocused on a dynamic policy for exhibitions, research and publications (and also acquisitions) around these femmes artistes.3 The investment of the Musée d’Orsay in thematic and specialized research is worthy of note: overall, it reflects a plan and ongoing investigation. The collection’s new exhibition circuit draws attention to women artists in particular, as well as to female patrons and art critics, creating a particularly complete map of their presence in late-19th century art – an effort that helps to contextualize the work of Berthe Morisot, the artist currently in focus at the museum.

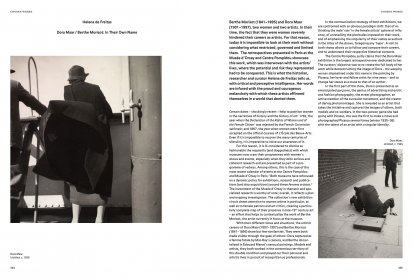

With their different times and situations, the artistic careers of Dora Maar (1907–1997) and Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) share but few similarities. They were both made visible through the gaze of others: Dora captured as a femme fatale by Man Ray’s camera, and Berthe immortalized in Édouard Manet’s sensual paintings. Models and artists, they both worked in the contentious territory of this double condition and played out their personal and artistic lives in pursuit of recognition as professionals.

In the communication strategy of both exhibitions, we are confronted with an obvious paradigm shift: that of rethinking the male ‘star’ in the female artists’ sphere of influence, of unravelling the platitudes imposed on their work, and of emphasising the singularity of their names as authors in the titles of the shows, foregoing any ‘hype’. A visit to both shows allows us to follow and compare their careers, and to understand their respective historical contexts.

The Centre Pompidou justly claims that the Dora Maar exhibition is the largest retrospective ever dedicated to her. The curators’ objective was to re-create the full body of her work while deconstructing the image of Dora – the weeping woman stigmatised under this name in the painting by Picasso, her lover and fellow artist for nine years – and to change her status as a muse to that of an author.

In the first part of the show, Dora is presented as an emancipated garçonne, the genius of advertising and erotic and fashion photography, the street photographer, an active member of the surrealist movement, and the creator of daring photomontages. She is revealed as an artist that takes the initiative and captures the images of others, both models and co-workers. In the two-person game she had going with Picasso, she was the first to make a move and photographed Picasso several times (winter 1935–36) with the talent of an artist with a singular identity.

In extensive series, the exhibition reviews the brilliance and experimental singularity of Dora Maar’s photographic work. But, in one room, it seems to come to a halt: there, a battle is staged. Picasso is known to have encouraged her and drawn her into painting, but he was also going to fight back. The artists are presented, face to face, engaged in an unequal combat. Dora falls into the trap of replication, leaves the comfort of her domain and paints, in the manner of Picasso, her lover’s portrait (1936), allowing him to declare ‘checkmate’.4 This moment signals the perilous crossroads of her artistic destiny. With an obvious pedagogic intention, the exhibition marks this turning point as the first moment in her decline. The following rooms describe the dark years of a woman and artist trying to survive and doubling down in her misjudgement. Only later, in old age, would she go back to photography and produce experimental and abstract images, markedly influenced by her spiritual retreats. Her life history is particularly relevant here, informing us of her experiences with psychotherapy, her hospitalization and her mystical crises. It is also worth looking attentively at the self-portrait she painted in 1947, depicting her sadness and deliberate seclusion: c’etait Pablo ou Dieu.

The exhibition definitively restores her status as an artist, while describing, with its vast and well-organised selection of works, the true scale and ambition of a multifaceted career. Yet, visiting this huge display, we are also confronted with, and left free to interpret, the dark light of a well-known star.

Just like Dora Maar, Berthe Morisot places work at the centre of her life. One of the founders of Impressionism, she was the only woman to show her work alongside the memorable names of her generation, claiming her place as one of the prominent figures of Parisian artistic life and its salons and official circuits. An agent of this renewal of painting and a proponent of its main themes, she was also the only female artist, a bourgeois one to be sure, to radically explore the possibilities of representing modern life, where she excelled both in the themes (le plein air, la lumière claire) and techniques (non fini). Morisot fought for recognition as a professional painter in times when women were not accepted at L’École des Beaux-Arts. Not a feminist herself, though a contemporary of the first French feminists, she dreamed of and sought after equal treatment: ‘I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal, yet that’s all I would have asked for, because I know I am of equal worth.’

Her artistic work was celebrated and critically referenced in her lifetime, but the image that took hold over time and through which she most often reaches us, is her black and intense gaze as immortalized in her portrait by Édouard Manet.

Berthe Morisot’s exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay takes hold of us with the wisdom with which it presents her (about 80) works and its ability to question the author’s lesser visibility when compared to her companions in the Impressionist adventure: Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Édouard Manet. Finally, redress is achieved and we can witness rich and pertinent dialogues between the works in the exhibition and the presence of these artists, her companions, in the museum.

Berthe was part of a generation of women still confined to the domestic sphere, but she knew how to extract from this family cocoon the essential ingredients to advance some of the most pertinent issues of the painting of her time, presenting them from her own perspective: the representation of the work of female child rearers and domestic workers, as well as the representation of active male parenting. This is how we circle back to the central issue of being both an artist and a model.

Berthe posed at least eleven times for Édouard Manet, with whom she maintained a close relationship, though she eventually married his brother Eugène. To this day, there are no known portraits of Édouard by Morisot (it seems he would not let himself be caught). Yet she painted Eugène caring for their daughter Julie in various domestic and family situations, inside and outside, which at the time was a daring representation of male parenting.

In her work, Berthe reveals intuition and resolve. Her self-portrait leaves no doubt: she looks directly at the viewer with brush and palette in hand, her frontal gaze and tied-up hair creating a daring pose that defied the feminine stereotypes of her time. The exhibition’s curatorial strategy demolishes the discourses of feminisation and guides our gaze towards the elements that signal the independence, singularity and subtle hauteur in her always surprising artistic themes and choices.

The act of choosing models and having them pose is a form of power, so accurately described by Paula Rego, many years after Morisot: ‘I wanted to do a girl drawing a man very much, because this role-reversing is interesting. She’s getting power from doing this, you see…’

*Translated by José Roseira

Share article